We live in a time when public and political discourse, especially in popular channels like Twitter, seems ever more coarse and cruel. In such a context, it might seem hard to delight in the romantic fancies of Valentine’s Day; its sweet sentiments seem to belong to an earlier age of refined manners, decorum and chivalry. Strangely, though, its history reflects a cynical era easily the equal of our own and a commentariat just as aghast at events.

Precisely who St Valentine was has long been lost in the mists of time. Generally agreed to be one of the martyrs who died for his faith in the early Christian church, the saint had little to do with romantic love or with the traditions now practised on February 14. While anonymous Valentine gift-giving between lovers – as well as between friends and family – is known to have taken place since the 17th century, the Valentine’s card as we know it today had its origins in the 19th century.

New technologies of the mechanised age enabled the mass production of printed missives, while the development of the modern postal system enabled cards to circulate far and wide. Commercial Valentine’s Day cards began life in the 1830s as a single sheet of paper, featuring a sentimental image and a short tender verse, designed to be folded into an envelope shape.

Innovations in manufacturing and the growth of celebrations in both Britain and America led to what was termed “Valentine Mania”. Increasingly ornate Valentine’s cards featured lace paper, decorative gilding, perfume, cushioning and a range of novelties from pressed flowers to pop-ups. These elaborate cards, which could be expensive, were designed – as now – to foster love and to consolidate courtships.

Insult to injury

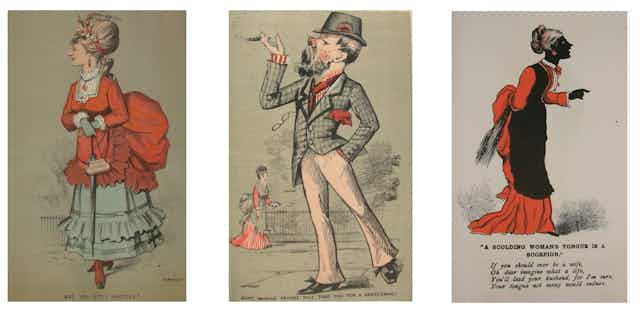

At the same time, however, a class of cards of a very different type gained popularity. Lacking the decorative refinement of the sentimental cards, these cheap and churlish Valentines were designed to insult rather than praise, and to chide rather than cherish.

The image they carried was designed to caricature the shortcomings of the recipient, whether in appearance, manners or morals, and the cruel verse hammered home the horrible message. The practice seems strange to us, but they were enormously popular; more popular even than their beautiful, more flattering counterparts. Little remembered now, the millions of vicious Valentines in circulation seemed, to many, to encapsulate the spirit of the modern age.

Commentary in the British popular press frequently despaired of vulgar Valentine’s celebrations. Articles with titles such as “The Decay of the Valentine”, “The Valentine has fallen upon evil days” and “Lost St Valentine”, charted the changing nature of the romantic feast. As the Bristol Mercury put it:

The sober, intellectual, satirical 19th century [might be] the days of advance …[but] in our onward march of civilisation we have trampled the maypole under our feet, dethroned the pretty queen, and turned cupid out of doors.

The Newcastle Weekly Courant argued, in 1891:

In “these last degenerate days”, Valentines have become ingenious machines, constructed with direct purpose of causing either a special glow of gratification or a gratuitous mortification and annoyance.

Modern life, it seemed, had got the Valentines it deserved. The Dundee Courier of 1898 suggested:

We have grown too matter of fact nowadays for Valentines. Sentiment has been laid aside with sewed samplers and our croquet sets, and the modern girl, with her bicycle, and her golf sticks, and her independence, has herself rung the death knell of poor St Valentine.

You can find these articles and more behind a paywall at the British Libary website.

Post-truth, post-love

What caused these bitter assertions? Largely, it was due to what the Daily Telegraph described as the “odious, insulting, gross, impertinent, vilifying, libellous, and mendacious concoctions” that circulated annually through the postal service. Many vile and foul items were handled by hardworking postmasters, from excrement to explosives.

A list published in The Graphic in 1880 included dead mice, rats, pigs’ trotters, and red herrings “sometimes dressed as babies and decorated with ribbons”. In this context, “mock” Valentines – as they were known – found their natural home as ready-made poison-pen letters. An earlier piece from the Newcastle Weekly Courant, 1857, had complained:

Stationers’ shop windows are full, not of pretty love-tokens, but of vile, ugly, misshapen caricatures of men and women, designed for the special benefit of those who by some chance render themselves unpopular in the humbler circles of life … The world is changing and hardening. Valentines are only bandied to-and-fro in these latter years by the knight and the dames of the till and of the counter. There are no Queens of the May – we observe with similar regret – to be found anywhere except among chimney-sweeps.

Although these complaints lay the blame at the door of the poor and coarse of manner, insulting Valentine’s cards were widely sent and received. Class and gender presented no barrier. There were cards designed to be sent to respectable occupations as well as those in lowly stations; women and men were equally mocked. The pretentious and the plain, the fat and the flirty were all victims of vinegar Valentine’s venomous darts.

World-weary 21st century citizens might consider our age to be supremely cynical, but in the case of cruel Valentine’s traditions, at least some things have improved.