Having reached a landmark agreement with China this week to limit greenhouse gas emissions, US president Barack Obama heads to Australia for the G20 summit of economic superpowers. The China deal will aid Obama’s efforts to prioritize discussion of climate change, laying the groundwork for a United Nations-led international agreement next year.

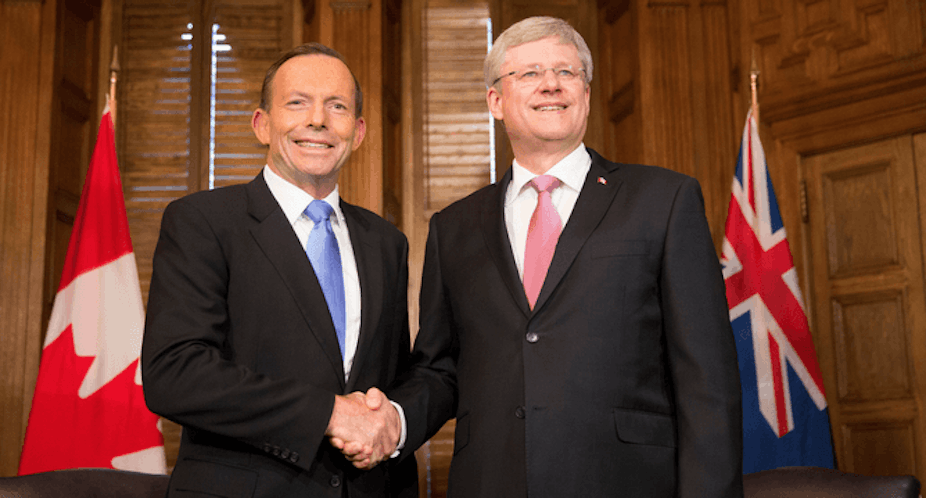

Yet despite building pressure, Australian prime minister Tony Abbott, as host of the summit, is likely to do his best to deflect any talk of international action. Along with Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper, the two conservative leaders of fossil fuel-rich countries present a major barrier to a global climate deal.

Formidable opponents

Earlier this year, Abbott repealed the nation’s carbon tax and abolished a commission tasked with communicating climate risks to the public. At the G20 summit, he has placed energy efficiency on the agenda, rather than focusing directly on climate change.

Abbott’s dismissive stance on climate change is shared by Harper. “No country is going to take actions that are going to deliberately harm jobs and growth in their country,” said Harper in a joint press conference with Abbott earlier this year. “We are just a bit more frank about that than other countries.”

Similar objections to climate action have long been voiced by US conservatives, and will be the focus of a Republican controlled Congress.

For Obama and his allies, despite the major stakes involved, there is no sure-fire strategy for overcoming opposition by conservative leaders who prioritize economic growth and the fossil fuel industry over climate action.

Yet recent research provides several key insights. The path forward starts with emphasizing a broader portfolio of policy actions and technologies than just carbon pricing and renewables. Such a strategy could help repair political divisions with conservatives abroad and at home. It could also catalyze the dramatic energy innovations that are needed on our tough, new planet.

What’s needed is more innovation

The study published this past week highlights the major technology hurdles we face in achieving the rapid reductions in greenhouse emissions necessary to avert the worse consequences of climate change. (The study was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation which has also supported my research.)

The authors analyzed 17 previously published expert scenarios that focused on the decarbonization (or removal of carbon) of electricity production. These scenarios are high-level thought experiments put forward by researchers to estimate the types of technology needed to achieve rapid global reductions in emissions.

Three of the models assumed that a transition away from fossil fuel generation could take place through nearly exclusive reliance on renewable energies led by solar and wind. These models also stipulated a near-total global phase out of natural gas, coal, and nuclear energy. In contrast, the other models envisage the widespread adoption of renewables alongside reliance on nuclear energy and the capture and storage (the process of capturing waste carbon dioxide and depositing it where it will not enter the atmosphere) of coal and natural gas emissions.

Each of the 17 analyzed scenarios is exceedingly ambitious. They do not account for a range of technical hurdles and social barriers, and assume unprecedented annual gains in energy efficiency.

Yet among the possible paths forward, as the authors of the recent study note, the three renewables-only scenarios stretch the limits of imagination. “It is likely to be both premature and dangerously risky to ‘bet the planet’ on a narrow portfolio of favored low-carbon energy technologies,” they warn.

As they estimate, to create an energy system without reliance on nuclear energy or carbon capture and storage would require an expansion of solar, wind, and other renewables that far exceeds the adoption rate of any single energy technology in global history.

“The clear picture that emerges from our analysis is that the climate race is an energy innovation race, not only in renewables but also in some of the big technologies like nuclear and carbon capture and storage,” Armond Cohen, co-author of the study and head of the Clean Air Task Force told me via email.

To achieve political agreement we need a diverse mix of solutions

Focusing on a broad portfolio of technologies is not only essential to meeting the decarbonization challenge, it is also necessary to broker political cooperation.

As a much-discussed series of public opinion studies by Yale University’s Dan Kahan and colleagues suggests, including nuclear energy and carbon capture and storage as part of the discussion of climate solutions helps bolster conservative faith that action can be consistent with economic goals.

Another study published last week by Duke University’s Troy Campbell and Aaron Kay lends additional support to the notion that a diverse mix of innovation-focused policies to tackle climate change are more likely to gain political acceptance.

In the experiment, among conservative-leaning Republicans, when the solution to climate change was presented as a carbon tax or another form of regulation, the solution tended to magnify Republican doubts about climate science. But in contrast, when the solution was presented as a free market approach that would help the US lead the world in “green technology,” a majority of Republicans agreed with scientific statements about climate change.

As Armond Cohen told me via email, citing similar findings by Kahan and others:

There are many reasons to support advanced nuclear, or carbon capture and storage, or even renewables, beyond climate change mitigation – rapid energy access, or energy security, or keeping the US at the nuclear energy global safety table, for example. Moreover, if these sources can be made less expensive, within spitting distance of fossil fuels, which is the goal of an innovation agenda, the political lift for their diffusion, where still necessary, becomes easier.

In both international negotiations and domestic politics, the more diverse the technologies and policies proposed to address climate change, the more likely people across the ideological spectrum are to accept the serious threats we face and to support policy action.

Focusing narrowly on carbon pricing and renewables is not likely to go very far politically, nor does such a focus offer a realistic strategy for curbing rapidly rising global emissions.