In Malaysia, disgruntlement and promise of change tends to result in the retention of the status quo. Enthusiastic reformers (pretenders or otherwise) are noisier rather than effective. Voters, at the end of the day, rarely want change, and rulers tend to bank on that. This was certainly the case with the ruling UMNO-Barisan Nasional stranglehold, which remained untouched after the election results over the weekend.

The lead up to the poll was one of agitation and interference. The independent media have been targeted, showing that hacking and disabling is not a preserve of the free, the radical and the unorthodox. One of the sites which has proven to be interesting reading is Malaysiakini, whose CEO Premesh Chandran insists has been gagged by what are claimed to be government sources: “during the 2008 election we were wiped off the internet”. In close results, few friends will be made.

Messages had been sent out before the votes en masse. Anwar Ibrahim, who “authored” one, encouraged “friends, family and neighbours to cast their ballots because every vote counts”. A few house-keeping issues were in order – note the polling station and destination. Note the route, be careful of traffic. Vote early to prevent voter fraud. Ignore intimidation. And, in bold:

Believe that your vote will change the future of our country and when you check the box on your ballot your act will be written in the history of Malaysia.

This is rather clever of Anwar, who is thatching ego with destiny in an effort to win. As it turned out, the ego of conservatism won out.

Voting through the day proved chaotic. The Star newspaper reported considerable crowds at bus and train terminals. As a voter, Shanaz Zain, told Al Jazeera :

This election is crucial for the country. This is the first time there has been such a narrow margin. It’s the first time that citizens are being heard by both sides. We are moving towards democracy.

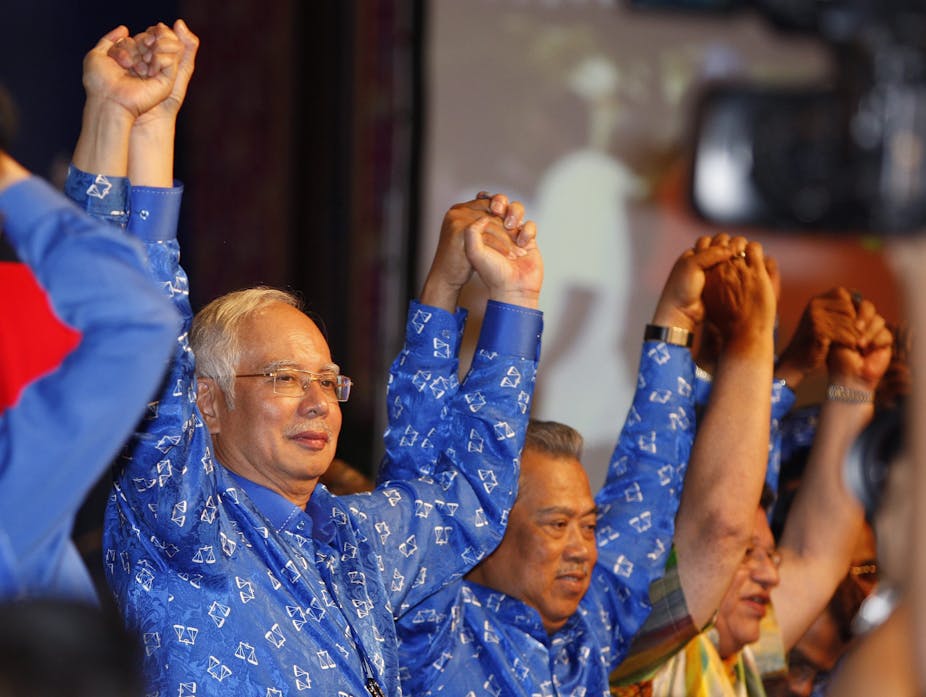

The results were not as close as expected, but nor were they as rosy for the victors. Najib Razak’s BN won the 112 seats needed for a simple majority, a figure reached before midnight. Predicted results show 133 seats, making it the worst result for the ruling party in its history. Considerable losses were made by the Malaysian Chinese Association, the second largest member of the coalition, whose voters found more promise with the opposition. The opposition’s result of 88 seats was, however, much lower than forecast. It ended up punching below its weight, failing to get the traction needed to get the backing of rural Malay voters.

Anwar, at the helm of the Pakatan Rakyat opposition, is certainly nothing if not ambitious. Being blooded by incarceration on trumped up charges tends to do that. It also encourages fear that the person once mistreated has scores to settle in procuring his broom. He has refused to concede defeat, seeking a “satisfactory answer” from the Election Commission “as to why this fraudulent process was being condoned or done”.

A few well-spiced allegations stand out: the use of foreign voters from Bangladesh, the Philippines and Indonesia by the ruling party to bring up the numbers, and sloppiness regarding the counting of 500,000 early and postal votes.

Anwar had promised that any transition would be peaceful. His opponents have suggested something more dramatic, claiming that, would he have won, an extremist coalition would take the reins. Certainly, the talk might be deemed extremist – turning back the ethnically based quota system privileging Malays over non-Malays is the sort of strong stuff the ruling parties have always feared. Affirmative action for the majority has been their motto since the era of redistribution ushered in by Mahathir bin Mohammad.

Besides, the governing party can boast of healthy foreign exchange reserves (US$44.36 billion) and healthy annual surpluses going back to 1998. All this, despite the country’s notoriety for ranking highly in the stakes of capital flight. Between 2001 and 2010, the equivalent of US$285 billion in illicit flows left the country. Of that figure, almost 20% involved bribery, theft, kickbacks and plain old corruption. Those figures, derived from studies done by Global Financial Integrity, err on the conservative side.

The prospects of a tight election had already driven some rich Malaysians to place their funds elsewhere. In 2012, Malaysian buyers, according to the estate agency Jones Lang & Wooten, accounted for 17% of all purchasers of new, exorbitantly priced residences in London. This may well continue – the fact that the ruling National Front will have nothing to cheer about other than staving off the promised ambush, and Anwar’s persistence – will continue to make the Malaysian political scene richly volatile.

The sole truth to be affirmed in this is one that Mahathir himself conceded prior to the vote – any government of Malaysia will need the involvement of “all three (major races) together with the people in Sabah and Sarawak”.