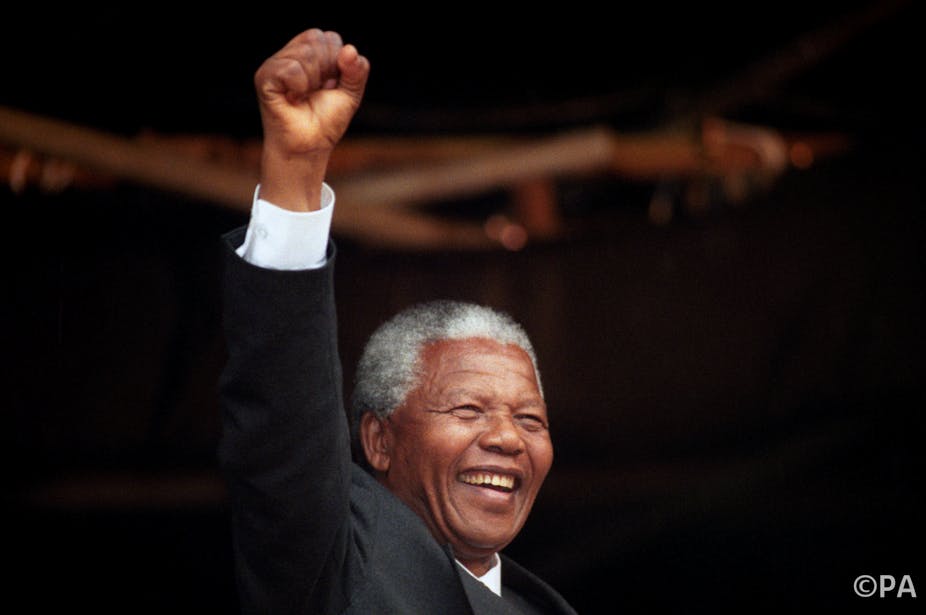

Nelson Mandela’s African name – Rolihlahla – means the one who shakes the tree, the one who unsettles the status quo.

When I was a student living amid the political violence of Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, my generation identified strongly with civil rights struggles across the world. The oppression of black South Africa was particularly egregious to us. In those years, Kader Asmal, later minister for water, then minister for education in post-apartheid South Africa lived in exile in Ireland, where he founded the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement, having earlier founded its British equivalent when living in London.

As students, we persuaded local businesses to boycott South African goods, performed street theatre, wore T-shirts calling for the release of Mandela.

After 1994, I went to South Africa and became a frequent visitor. In 1999 I took a group from Northern Ireland and Kader Asmal received us as minister for education. In his state reception room, we sang and laughed, remembering his time in Ireland. In 1999, I was in the parliament on Mandela’s penultimate day as president of South Africa.

It was after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 that Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK for short, “the spear of the nation”) was founded as the armed wing of the African National Congress. Mandela, one of the founders, saw it as a last resort:

It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle, and to form Umkhonto we Sizwe. We did so not because we desired such a course, but solely because the government had left us with no other choice.

Initally, MK limited itself to sabotage in order to avoid civilian casualties: “Sabotage did not involve loss of life, and it offered the best hope for future race relations. Bitterness would be kept to a minimum and if the policy bore fruit, democratic government could become a reality,” was what Mandela said of the strategy.

In practice, events such as the 1983 Church Street bomb in Pretoria resulted in 17 civilian deaths; the 1985 shopping centre explosion in Natal killed five civilians; a bomb in a bar in Durban killed three civilians, which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) described the latter as a “gross violation of human rights”.

The MK mining of rural roads in the then-Northern Transvaal from 1985 to 1987 was abandoned due to the high rate of civilian casualties. The TRC criticised MK’s use of landmines, but gave the ANC credit for stopping their use.

Thatcher and the ‘terrorist’

Margaret Thatcher denounced Mandela’s liberation movement as a “typical terrorist organisation”. Against the tide of international opinion, she consistently opposed sanctions against South Africa’s white minority government, positioning herself as a friend of the regime. In 1985, she wrote to PW Botha advocating both the release of Mandela and political dialogue, which she saw as a “skillful move”.

When, after his release in 1990, Mandela declined to meet Thatcher while in London, Conservative MP Terry Dicks asked:

How much longer will the prime minister allow herself to be kicked in the face by this black terrorist?

The application of the term “terrorist” was a move to de-legitimise the person so labelled while legitimising exceptional and extra-legal measures against them. Mandela’s imprisonment and the campaign against the ANC and MK and the abomination that was apartheid was seen by Thatcher and many others as legitimate and their struggle against it was “terrorism”. Might, so goes the argument, is always right.

By 1996, Mandela had been elected president and on his return to London, met Thatcher, was accorded the honour of addressing both Houses of Parliament in Westminster Hall and of having tea with the Queen.

Mandela went on to occupy a role as a statesman and world leader. Awarded the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize with F. W. De Klerk, Mandela’s magnanimity to former enemies helped establish ubuntu as the method to achieve national unity and reconciliation within South Africa. Mandela went on to advocate this approach internationally, albeit with mixed success in Nigeria, Zaire and Lesotho and he attempted to mediate relations between Libya and the US.

In 2005, when Mandela’s son died of an HIV/Aids-related illness, Mandela redoubled his efforts to raise global awareness and funds to fight HIV/Aids pandemic in Africa. In 2007, he founded The Elders with statesmen and women such as Kofi Annan, Marti Athasaari, Jimmy Carter, Desmond Tutu, Mary Robinson, Graca Machel and Aung San Suu Kyi as to act as international peace and human rights advocates. They have taken initiatives in Cote d'Ivoire, the Middle East, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Korea.

Now that he is gone and many of us are left without the political father that he was, we must emulate that sense of justice, that courage to fight for that justice, while understanding, as he did, that violence is the truly desperate last resort, not ever the preferred course of action.

That expansive generosity of spirit that does not bear grudges and that embraces those who harm us makes us more, not less secure, stronger, not weaker. It endows us with the moral qualification that Madiba embodied, to shake the tree when it is the right thing to do. May his spirit continue to watch over Mother Africa.