Australia has long shown disregard for international conventions surrounding refugees. It labels asylum seekers in detention on Manus Island as “transferees”, also frequently referring to those who arrive by boat as “Irregular Maritime Arrivals” and “queue-jumpers”.

In calling asylum seekers protesting on Manus Island this week “aggressive” and “irresponsible”, Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has demonstrated just how brazenly Australia both distances asylum seekers geographically, through offshore policies, and in the minds of the Australian public by controlling the narratives about their behaviour.

Harsh labels and harsh policies

Labels are crucial in matters of forced displacement and refugee protection. The UN Refugee Convention details at length who is a refugee, their rights and a state’s responsibilities towards them.

Australia has a complex legislative framework setting out its obligations towards asylum seekers. Around the world, refugee lawyers and advocates spend a lot of their time ensuring that the rights of asylum seekers and refugees – as distinct from migrants – are upheld and their protection needs are met. This is not for want of anything better to do.

The first component in ensuring that Australia’s international obligations towards displaced persons are met is the integrity of the systems we have to determine who is, or is not, a refugee or asylum seeker. The second is showing concern for their plight through the careful use of language that we employ in our representations of them.

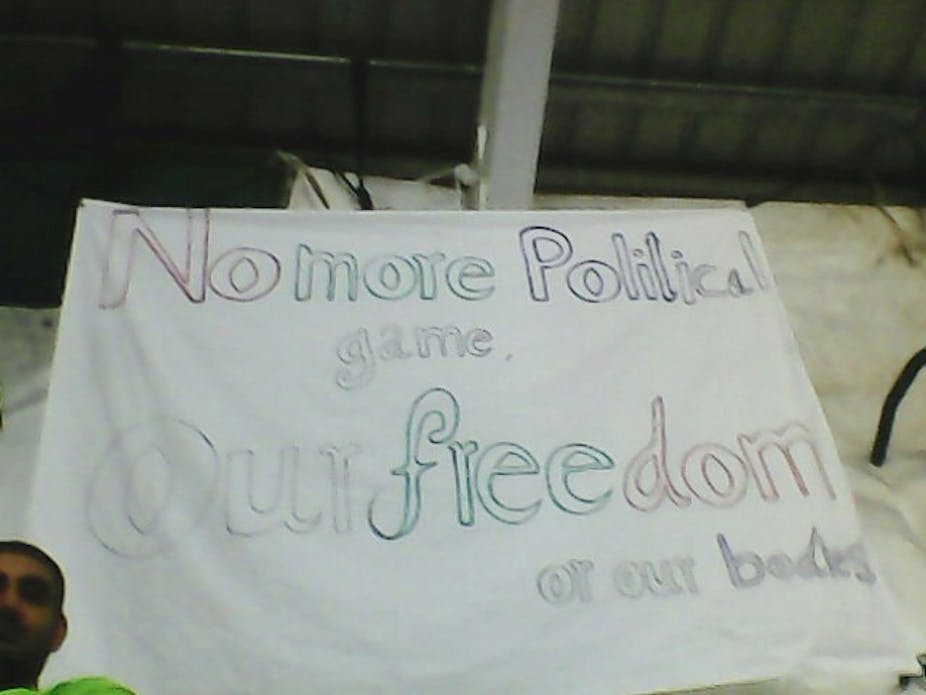

As has been argued by others, asylum seekers protesting on Manus Island are trying to voice their distress and despair. They hope by doing so to invoke our concern and attention.

Closer to home, refugees and settlement workers often fear the consequences of speaking out publicly. It may be a breach of their code of behaviour or the organisation’s contractual obligations with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, as the Jesuit Refugee Service has pointed out.

These concerns are not unfounded. In mid-2014, the Refugee Council of Australia had its federal government funding cut by the then-immigration minister, Scott Morrison. This was because it was an advocacy group that was perceived to be critical of the government.

Ignoring international advice

In other parts of the world, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and NGOs go to great lengths to showcase the voices of refugees and to empower them to speak.

The UNHCR recently introduced a crowdsourcing platform, UNHCR Ideas, to generate ideas from refugee communities that could be tested in the field. This reflects a widely accepted paradigm that projects that are participatory and inclusive have the best chance of success.

Going against this practice, journalists are regularly denied access to Manus Island and the voices of asylum seekers are largely absent from debates relevant to them. NGOs sometimes also fall into the familiar “victim trope” when seeking to invoke our sympathy for asylum seekers and refugees. This is despite voluntary guidelines such as the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief, which stipulates that:

… in our information, publicity and advertising activities, we NGOs shall recognise disaster victims as dignified human beings, not hopeless objects.

Two positive examples are World Refugee Day, when the resilience and agency of refugees and asylum seekers is celebrated, and Refugee Week, during which the positive contribution made by refugees and former refugees is promoted.

The Australian public deserves to be able to make up its own mind about asylum seekers, rather than being told that protesters are aggressive and irresponsible. One simple way to change this is by providing media access to detention centres and giving settlement workers who want to speak publicly permission to do so.

The Australian government must also re-think its entrenched and often hardline attitudes towards asylum seekers and refugees. As the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, said recently:

… the lack of concern that we see in many countries for the suffering and exploitation of such desperate people is deeply shocking. Indeed perhaps we can even say there is a mean-spiritedness that marks the general attitude in some countries … Rich countries must not become gated communities, their people averting their eyes from the bloodstains in the driveway.

Perhaps the next time we hear the government vehemently telling Australians what we should think about asylum seekers and refugees, we should ask to hear the other side of the story too. Australians deserve a more inclusive and representative dialogue on matters of refugee protection.