The Australian Rules Football Women’s (AFLW) season is upon us for 2018, and will feature an expanded pool of talented female athletes battling it out on the footy field.

An elite female football competition and career pathway is long overdue. But it’s worth pausing slightly to consider the AFL’s “fast-track” approach to launching the AFLW.

Although play-reading and decision-making skills are typically high in women coming from sports like basketball, coaches and fans alike might need to show a little patience as players build their finer skills and physical preparedness for the unique demands of Australian football.

Read more: Why it might be time to eradicate sex segregation in sports

Talent transfer

The fast-track push in AFLW has relied on a “talent transfer” approach. This model recruits successful athletes from other sports, and who have some background in Australian football.

For instance, the inaugural AFLW best and fairest and premiership player Erin Phillips (Adelaide) also played basketball in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) until May last year. Number 3 draft pick Chloe Molloy (Collingwood) gave up a USA college basketball scholarship to pursue her AFLW dream. Brianna Davey (Carlton) was a former goal keeper for the Australian Matildas (our national women’s soccer team).

So what is it about other sports that allow these women to be successful on the football field with seemingly limited AFL experience?

Read more: Growth of women’s football has been a 100-year revolution – it didn't happen overnight

Invasion sports

The AFLW belongs to a group of sports commonly referred to as invasion sports – other examples are basketball, soccer and netball. Invasion sports’ shared characteristic is that the objective of the game is to invade an opponent’s territory to score. As a result, these sports share similar perceptual and decision-making requirements such as spatial awareness (relative to the ball) and anticipation of play.

Research from the elite men’s AFL competition shows that players classified as “expert” level (when compared to non-expert players) have dedicated relatively more training hours to non-AFL invasion sports; basketball in particular is a strong donor sport. The transferability of game-sense skills from one invasion sport to another means these talent transfer athletes are a high priority for selection into AFLW.

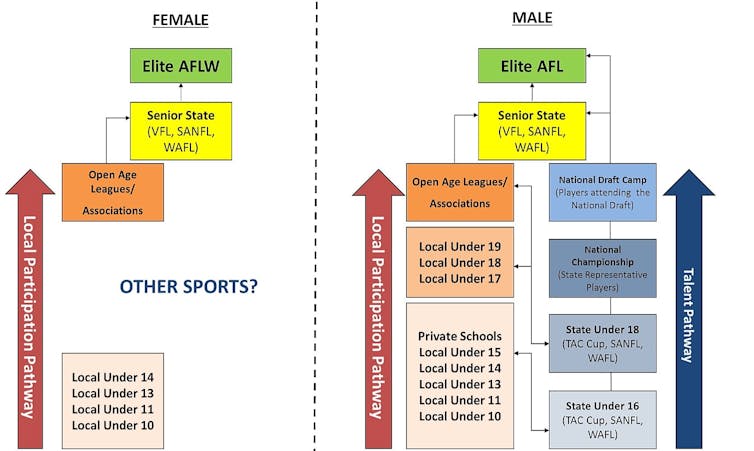

Traditionally, female footballers have fought for the opportunity to play football, with an age cap of 14 years for mixed-gender football competition forcing many girls to leave the sport. As a result, many players pursued other sporting careers.

Tanya Hetherington (GWS Giants) sums up their struggle, saying:

I was a footballer in a netballer’s body.

Women and girls are flooding back to AFL, with the rise of female leagues across the country finally providing an opportunity to play football.

Gaps in development

The finer skills (such as kicking, handballing, tackling) and physical preparedness (sport-specific fitness, injury prevention) for footy may be absent from AFLW players’ training backgrounds. Previous gaps in the AFLW talent development pathway means players need time to develop.

So a little patience from coaches, athletes and spectators is required. AFL is a highly skilled sport, and while the AFLW players may be skilled in reading and reacting to play, limited years of deliberate practice means they may lack kicking, handball and tackling skills necessary to be an effective footballer in the short term.

Of biggest concern is the 360 degree contact element of AFL and, related to that, physical preparedness of players first entering or re-entering the AFLW environment.

The vast skill spectrum of players at the elite level creates a skill imbalance within and between teams. We know from research in female soccer that highly skilled players are at greater risk of injury compared less-skilled players, but less-skilled players were more likely to avoid contact situations.

However, the nature of AFLW means contact situations are unavoidable (e.g. tackle by opposition, pack marks, bumps). Heavy contact is not common in most sports that AFLW players transfer from (including soccer). As such, players with inexperience in contact skills are at a greater risk of serious injury (such as those affecting the head and spine, or joint dislocations) because they are not accustomed to laying or receiving a tackle or bump.

Done an ACL

A serial offender on the injury list is the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL), a ligament that provides stability in the knee. The first 4 rounds of the AFLW 2017 season witnessed four season-ending ACL injuries.

It is well established that female athletes are predisposed to the ACL injuries. The female pelvis is wider, creating a greater angle between the knee and the hip (the quadriceps-, or Q-angle), with the subsequent force transfer between the joints placing the knee at risk. Also, estrogen surges during the first half of menstrual cycles is a possible contributor to ACL injury, because the hormone can effect joint laxity (how loose the joint is are).

Further to this, other characteristics commonly involved in ACL injuries are all present in AFLW, these being;

- contact directly to the knee

- change of direction or awkward landing (non-contact ACL’s)

- reduced neuro-muscular control with limited sport-specific training (physical and skill)

- poor physical fitness and/or fatigue caused by match play and inadequate physical preparation

- friction between football boots and turf.

Building the foundations

At the moment, you could argue that AFLW players skill and physical preparedness is underdeveloped for training and game requirements. Teams should avoid fast-tracking players’ physical training to meet the “elite” title.

Skipping steps when building physical foundations (e.g. safe jumping/landing, change of direction, deceleration, mobility, strength) does not support, but hinders elite performance. The AFLW should ensure that player skill and physical foundations are strong before attempting to build the house.