Skulls, the ship’s figurehead and other artefacts from the wreck of a 1545 Tudor warship have been made available to peruse online in 3D reconstructions. But why did she sink? The answer is more elusive than you might assume.

Many people think that disaster hit on her maiden voyage, sailing out of Portsmouth Harbour into the Solent. This is simply not true. The Mary Rose sank at the front of an English fleet of about 80 ships which were doggedly defending England from a French invasion. The French fleet of around 200 ships, carrying an army 30,000 strong, was anchored just off the eastern end of the Isle of Wight. The fate of England, and King Henry VIII’s crown, hung in the balance on July 19 1545 – a calm, hot, summer Sunday.

Henry’s main army was in France, defending the English possession of Calais and the town of Boulogne. So all he could muster at Portsmouth was a scratch force of inexperienced militia and farm-hands – 12,000 ill-equipped and untrained men. The English were outnumbered nearly three to one on both land and sea, so the only way of thwarting a full-scale invasion was to prevent the French from landing.

Traditional thinking says that she was blown over by a freak gust of wind as reported by an eyewitness to the events, while another contemporary account suggested that the crew were incompetent and unwilling to follow orders. More recently it was said that many aboard were Spaniards who could not understand English instructions, leading to confusion and chaos. But these seem to me to be very unsatisfying reasons for the catastrophic loss of Tudor England’s finest ship and consequently I attempted to develop a better understanding of the Battle of the Solent and the events that surrounded the loss of the Mary Rose.

Reconstructing the battle

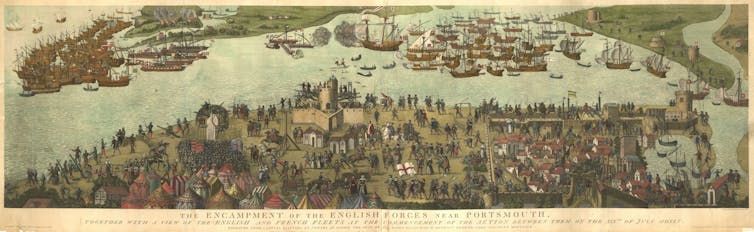

I did so by assimilating both geographical and historical records in order to reconstruct the the battle. In addition to the written accounts, a contemporary painting of the event – the original of which was more than 20ft long and once adorned the dining parlour of Cowdray House in Sussex – has proved remarkably useful. It depicts the entire battle scene and was probably painted between 1545 and 1548. The original was lost to fire in 1793 but luckily copies had been commissioned 20 years earlier.

The picture shows the French invasion fleet off the Isle of Wight on the left and the English fleet arranged across the Solent to the right. Henry VIII is shown riding towards Southsea Castle (followed by Sir Anthony Browne, Master of the King’s horse, who commissioned the painting) and right in the middle of the picture the masts of the Mary Rose can be seen breaking through the surface of the sea, with a sailor waving very animatedly from a platform at the top of the main mast. Surrounding him are the floating bodies of drowned sailors and several small boats trying to rescue any survivors.

Using the Cowdray picture and modern digital mapping technology it was possible for me to recreate and map the positions of all of the ships, troops and installations across the Solent battlefield. The picture is remarkably accurate in its presentation of the geography of the Solent. Known landmarks, such as forts, churches and creeks, still visible in the modern landscape, enable good positions for the ephemeral elements such as ships and troops to be determined.

It was also possible to reconstruct the tidal currents for the day of the battle. Consequently we can work out how the two opposing fleets likely conducted the action between them. This ties together the written accounts from the time and the archaeological evidence and places it within the geographical context of the Solent.

Tidal tales

A tidal reconstruction shows that from 8am to around midday, the Solent’s flow was westerly. As the day was calm and sunny and there was no wind, the English ships would not have been able to move, and so would have remained anchored at Spithead, the tide shifting their bows to face towards the French. This detail is crucial, because the English ships did not have any guns that could fire directly forwards, only off to the port or starboard sides. This means that for four hours in the morning, the French would have been favoured by the tide, able to send in their advance attack of five galleys directly towards the bows of the English ships without the English being able easily to return fire.

These Mediterranean galleys were fitted with either two or four large guns firing directly forwards and could shoot from a relatively long range. In the morning, the French therefore had the advantage. Unlike the English, French galleys were powered by oars, rowed by prisoners-of-war and convicts, and could move independently of wind or tidal current. So, for at least four hours the French could have been firing at the English ships’ bows, relatively safe themselves. Together, these details suggest that it is likely that the Mary Rose would have sustained damage to her bow in the morning. An account by French eyewitness Martin Du Bellay records:

Favoured by the sea, which was calm, without wind or strong current, our galleys were able to manoeuvre at their pleasure and to the disadvantage of the enemy who, not being able to move for want of wind, remained exposed to the fire of our artillery.

It seems unlikely, given that they could get close to the English ships, that they would have missed their targets, so they may well have damaged the bow of the Mary Rose. (At this point in time, much of the bow structure of the Mary Rose is yet to be excavated from the seabed and so there is no archaeological evidence of such damage.) Of itself, a damaged bow wouldn’t be too much of a problem, although she may have been shipping considerable water into her hold. Intriguingly, the Mary Rose’s pump was not found in its proper position when excavated and it had been partly dismantled, not functional at the moment the ship sank – perhaps it broke through overuse?

On the attack

By mid-afternoon it is normal for a sea breeze to blow up in the Solent. This would have afforded the Mary Rose the opportunity to set sail and bring her broadside armament to bear against the attacking French galleys. At about 4pm or 5pm the Mary Rose embarked on a northerly passage, the direction in which she was travelling when she sank, across the Solent to engage the French.

Archaeological evidence tells us that some of the starboard guns were fired, so she must have encountered the enemy. She continued passage northwards but would have been rolling and sailing sluggishly if she had been hit earlier in the day and shipped water. Having fired their guns, the crew of the Mary Rose would have known that they were in trouble, feeling the uneasy movement of the ship beneath their feet. I suspect that it was their aim to run her aground on Spitbank, just 600 metres ahead of where she sank.

Six minutes more sailing and she would have been safe. But had she rolled just a little bit too far and for a little too long, allowing the open gun ports to dip below the sea, the sudden inrush of a mass of water onto the main gun deck would have completely destabilised the ship and she would have sunk within seconds.

The sinking of the Mary Rose claimed the lives of around 500 men on board. Only 35 were reported saved. I believe that the crew of the Mary Rose have been unfairly maligned by previous suggestions for the cause of the sinking. No evidence suggests that they were incompetent or ill disciplined, and on such a calm day a freak gust of wind seems unlikely. But until – or if – the bow is recovered, my theory remains just one of a number of possibilities.