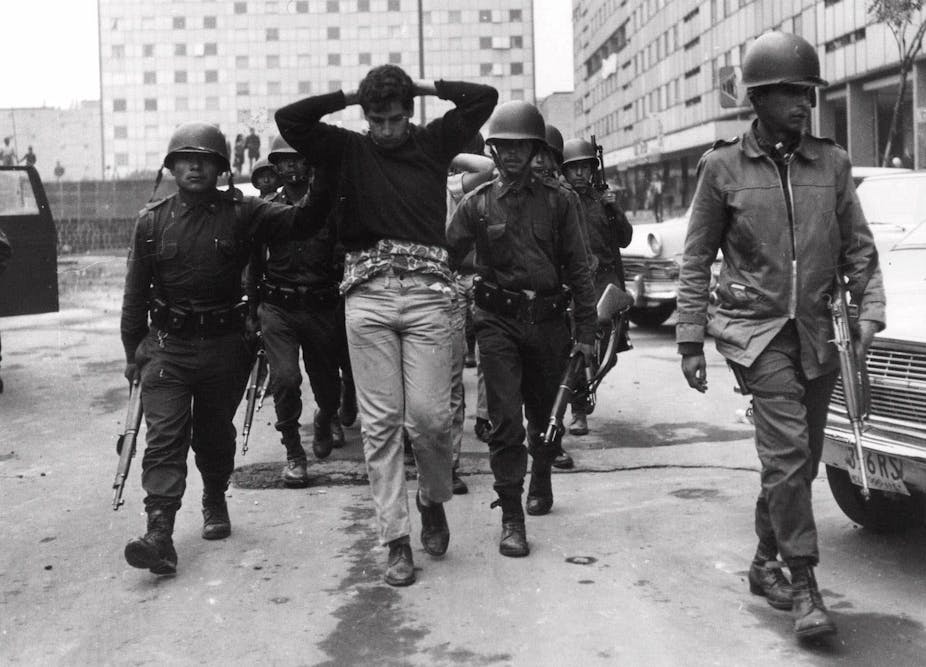

Ten days before the opening ceremony of the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, uniformed soldiers and rooftop snipers opened fire on student protesters in a plaza in the capital city’s Tlatelolco neighborhood.

Hundreds of pro-democracy demonstrators, who were rallying against the country’s semi-authoritarian government, were gunned down.

Foreign correspondents reporting from Tlatelolco estimated that about 300 young people died, although the toll of the Oct. 2, 1968 massacre remains contested. Over a thousand people who survived the shooting were arrested.

Tlateloloco was not the first time Mexico’s government would send the army in to kill its own citizens. Nor, as my research on crime and security in the country shows, was it the last.

Mexico’s perfect dictatorship

Technically speaking, Mexico was a democracy in 1968. But it was run by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, the same party that governs it today under President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Using press manipulation, electoral fraud and coercion, the PRI won every presidential election and most local elections from 1929 to 2000. In the words of the Nobel Prize-winning author Mario Vargas Llosa, it was a “perfect dictatorship” – an authoritarian regime that “camouflaged” its permanence in power with the superficial practice of democracy.

The PRI kept kept a tight rein on Mexico during its 80-year rule.

In the 20th century, Mexico had none of the wild violence that ravages the country today. It prospered economically and modernized rapidly.

But the PRI demanded acquiescence in exchange for this peace and stability.

The party bought off potential political opponents and ostracized members who wanted to reform the party. It gave rabble-rousing union leaders positions of power. It killed, jailed, tortured and disappeared leftists, dissidents, peasants or Marxists who challenged its authority.

But it did so in secret. When soldiers sent by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz killed scores of students exercising their constitutional right to peaceful protest in broad daylight and cold blood, something the Mexico’s national consciousness shifted and snapped.

It would take Mexicans another four decades to unseat the PRI, electing in 2000 Vicente Fox of the National Action Party – the first non-PRI president to run modern Mexico.

But most thinkers and historians agree that Tlatelolco was when democracy’s first seeds were planted. After the massacre, a “tradition of resistance” took root in Mexico.

1968’s summer of revolution

The Tlatelolco massacre came after a tense summer of student demonstrations.

Triggered by an aggressive police intervention in a gang fight in downtown Mexico City in July 1968, young Mexicans – like their counterparts in the United States and worldwide – engaged in various acts of civil disobedience.

Throughout late summer, Mexico City saw peaceful marches, demonstrations and rallies. The students demanding free speech, accountability for police and military abuses, the release of political prisoners and dialogue with their government.

The uprising brought bad publicity at an inconvenient time. Mexico was about to host the 1968 Olympics. President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz wanted to showcase a modern nation at the forefront of emerging economies – not unruly leftists decrying an authoritarian government.

Díaz Ordaz said the protesters were Communist agents sent by the Cubans and Soviets to infiltrate his regime – a claim the Central Intelligence Agency debunked in a now-declassified Sept. 1968 report.

By early October, with the Olympics rapidly approaching, the government had decided to put an end to the unrest. So when students planned an Oct. 2 rally at the Plaza of the Three Cultures in Tlatelolco, Díaz Ordaz sent undercover agents and soldiers in.

Their mission, as some of the raid’s organizers later admitted, was to delegitimize Mexico’s pro-democracy movement by inciting violence. Plainclothed soldiers from Mexico’s “Batallón Olimpia,” created to maintain order during the Olympics, opened fire on the crowded plaza.

Díaz Ordaz claimed that he had saved Mexico from a communist coup.

But even Lyndon B. Johnson administration’s – which had no sympathy for communism – described the crackdown as a “gross over-reaction by the security forces.”

No one was ever punished for the murders.

50 years to freedom

Each year, Mexicans commemorate the Tlatelolco massacre with marches and rallies.

For the past four years, these events have coincided with nationwide demonstrations over the unexplained disappearance of 43 student activists from Ayotzinapa Teachers’ College, in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, on Sept. 26, 2014.

The students were traveling via bus to Mexico City to attend a commemorative rally for the victims of Tlatelolco and engage in civil acts of disobedience along the way – an annual tradition at the college.

According to the government’s official investigation, police in the town of Iguala confronted the caravan under instructions from the town’s mayor. His wife had a party that day, the report says, and he didn’t want any disturbances.

The officers opened fire, killing six students on the bus. The remaining 43 passengers were then allegedly taken to a police station, where they were handed over to a local drug gang, Guerreros Unidos, which is alleged to have ties to the mayor. Gang members say they took the 43 students to a local dump, killed them and burned their bodies.

That horrifying tale is the official story endorsed by President Enrique Peña Nieto, whose six-year term ends in December. Iguala’s mayor, his wife and at least 74 other people were arrested for the disappearance and murder of the Ayotzinapa students.

But an international team of forensic investigators could not corroborate this story. They found no evidence of the students’ remains at the dump. In fact, they determined, it was scientifically impossible to burn 43 corpses at that site.

They believe it is more likely that the Mexican army – and therefore the federal government – was involved in the disappearances.

In June 2018, a federal court re-opened the Ayotzinapa case and ordered the creation of an Investigative Commission for Justice and Truth to clarify what really happened to the 43 students.

“They were taken alive,” their parents insist. “We want them back alive.”

Transforming Mexico, again

Forty-six years after the Tlatelolco massacre, almost to the day, this brutal abuse of power by President Peña Nieto and his PRI party – which had retaken power in 2012 – rekindled something of the revolutionary spirit of 1968.

In July, Mexican voters once again rejected the PRI, handing a landslide presidential victory to Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a leftist outsider who promised to “transform” the country.

López Obrador, who takes office in December, supports launching a new investigation into the 43 missing students.

But he also plans to continue using Mexico’s military – the same efficient killing force that fired on students at Tlatelolco and allegedly disappeared them in Ayotzinapa – in law enforcement duties.

This, in my assessment, is a dangerous mistake.

According to an analysis done by Mexico’s CIDE university, between 2007 and 2014, in armed confrontations the army killed eight suspected criminals for each one it wounded and arrested. In most countries, the ratio goes the other way.

As CIDE legal scholar Catalina Pérez Correa has written, using Mexico’s army as police carries the same risks today it did in 1968 – and in 2014, for that matter.

President-elect López Obrador has declared that under his government Mexico’s military will be not an “instrument of war” but an “army of peace.”

The ghosts of Tlatelolco and Ayotzinapa are a reminder that all Mexicans should have their doubts.