John Alec Baker’s The Peregrine is both a brutal and beautiful observation of this bird of prey, which at the time of publication in 1967, was close to extinction. Transcending both nature writing and environmentalism, his novel continues to inspire and speak to new generations.

A new exhibition called Restless Brilliance: The Story of J.A. Baker and The Peregrine is on at Chelmsford Museum, Essex, until November 3. It showcases Baker’s life, highlights how The Peregrine still resonates today, and considers how his nature writing influenced the Essex landscape.

His legacy is not only in the beauty of The Peregrine’s prose, but in his archive, donated to the University of Essex in 2013, which I oversee as curator. When people visit the archive, they are always drawn first to Baker’s binoculars. They want to lift them up, look through them, and try and step into his world. To hold them and look up at the sky – Baker’s Essex sky.

Born in Chelmsford, Essex in 1926, Baker dreamed of being a writer, but his father deeply disapproved of the idea. He found love, got married, and worked in various jobs he disliked, eventually settling at the Automobile Association.

Baker saw his first peregrine in the winter of 1955 and spent the next ten years systematically observing and recording them in the Essex countryside, writing “I spent all my winters searching for that restless brilliance, for the sudden passion and violence that peregrines flush from the sky.” He had found his muse in the peregrine.

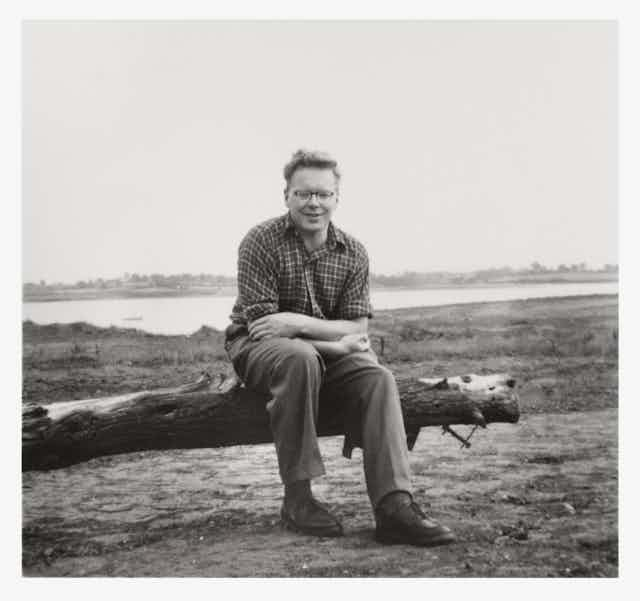

The Peregrine recounts the story of a bird over ten winters, but Baker’s archive is the story of a very private man. Spanning his lifetime, the collection includes early correspondence, photographs of him and his wife Doreen taken by each other on trips to the Blackwater Estuary, and his ornithological material such as well-worn maps, birdwatching diaries, and his many binoculars and optics.

Sarah Harvey from Chelmsford Museum and I spent two years bringing Baker’s archive alive in the exhibition. But this story is not just about Baker. The exhibition also highlights the recovery of peregrines, which thanks to work by ornithologists and naturalists, UK breeding pairs are at their highest levels this century, with populations rebounding in East Anglia.

Baker’s landmark book, The Peregrine, is part-love letter and part-eulogy to a bird of prey under threat from human actions. Between 1940-1946, the government’s Destruction of Peregrine Falcons Order resulted in a cull of hundreds of peregrines to protect carrier pigeons that they prey on.

Then the rise in use of agricultural pesticides caused a decline in their reproduction rates and reduced the amount of calcium carbonate in their eggs causing them to thin and become accidentally crushed in their nests.

Baker knew where to lay the blame when he wrote “many die on their backs, clutching insanely at the sky in their last convulsions, withered and burnt away by the filthy, insidious pollen of farm chemicals”. The Peregrine became a call for greater environmental protections to save them from extinction.

Leaving a legacy

The Peregrine is highly regarded as a great example of nature writing. Some people have been drawn to the evocative language and the way he described his beloved peregrine and Essex landscape, others to his anger over the consequences of our actions and others still to how it made them feel.

TV presenter and naturalist Chris Packham described it as: “the very finest of prose, inspired by nature”. The Peregrine has influenced other high-profile naturalists and conservationists including Sir David Attenborough, who narrated the audiobook, and author Robert Macfarlane.

Baker’s legacy resonates deeply with inspiring filmmakers such as Shaunak Sen and Werner Herzog who said of The Peregrine: “It’s a most incredible book. It has prose of the calibre that we have not seen since Joseph Conrad — an ecstasy of a delirious sort of love for what he observes”.

Today, peregrines are once again back in Baker’s Essex sky. Alongside Hetty Saunder’s brilliant biography of Baker, My House of Sky (2017), the exhibition draws upon his archive and some little-known letters of his from the Richard Burton Archives at Swansea University that give an extraordinary glimpse into his life.

In a 1946 letter to a friend, Baker wrote: “I feel a power within me that, if I do not cease to work and do not break fault with my ideals, will, I know carry my words to immortality.”