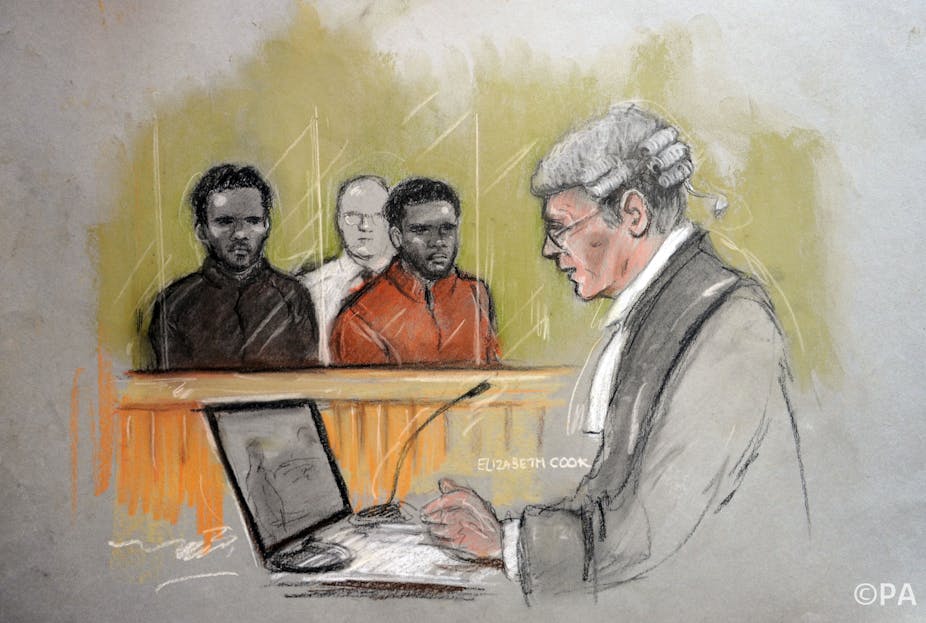

The trial of Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale has concluded with the jury finding them guilty of murdering soldier Lee Rigby. Their claims that they were, in the words of Adebolajo, “soldiers of Allah” and that the killing was an act of war rather than murder were dismissed by the jury in less than two hours.

The pair’s statements regarding their religious motivation has led to many headlines and a review of the government’s recent Prevent strategy. However, the prosecutor in the case was right to warn that Islam was not on trial (at least in the courtroom). As I have written before, to describe Adebolajo and Adebowale’s actions as Islamic is wrong; indeed, that would be as erroneous as the argument that the West’s actions in Iraq and Afghanistan are Christian, although of course this falsehood is also claimed in some places.

Instead of focusing on whether Islam was at fault, it is more helpful to look at the specific ideology at play. As one of my colleagues Linda Woodhead has pointed out, this is often very different to the idea of established religions as they are commonly conceived.

Sacred grounds

One way that my research has focused on investigating violent religious and non-religious ideologies is through looking at what people hold sacred. We might understand this sacred as a set of non-negotiable beliefs. Adebolajo and Adebowale wholeheartedly believed they were part of a war – the world for them was divided inextricably between what they understood as believers of Islam, and the West. Their reaction to the invasion of Islamic countries was to extend the war to the streets of Woolwich, with horrific consequences. So committed were they to their cause that they actively sought martyrdom as a result of their actions – something the jury seemed to accept with the not guilty verdict to the charge of attempted murder of a police officer.

They believed their actions to have sacred legitimacy, that their actions were blessed by Allah and they interpreted His blessings through the success of their attack. This blessing and indeed their belief in Allah are further non-negotiable beliefs.

Of course, we all have non-negotiable beliefs and values. They define us and the groups we belong to. Whether they are state borders, flags, morals on sexual norms or commitments to freedom of speech, these sacred values can be found in secular and religious spheres of life. But for most of us our responses to threatened or actual transgressions of these values are contained within the rule of law and, even where they are not, they rarely take the extreme shape we witnessed in the murder of Lee Rigby.

These values are informed by many ideologies, differently interpreted by each of us, and it is difficult to establish the extent to which they contribute to violent action. Indeed, some researchers have questioned the causative role that ideology plays in violence. Writing about his Demos report The Edge of Violence, Jamie Bartlett pointed out that religion is often a justification, not a motivation, for acts of violence and, in the US, John Horgan has argued that radical beliefs do not necessarily lead to violent action.

With funding from the RCUK Global Uncertainties Programme, Kim Knott and I are exploring the links between ideology and violent action in more depth. We’ve been bringing together researchers and practitioners from across university disciplines, government departments and think tanks in order to understand it better. We know from past research that factors such as past criminality and belonging to extremist networks – both of which can be seen in this case – can play a role in subsequent violent behaviour.

How much of a role it played in this case we don’t know, but from the evidence of Adebolaje, the murder of Lee Rigby does seem to have a clear ideological motivation. In their eyes they were soldiers of Allah, even if most Muslims and society as a whole dispute that.