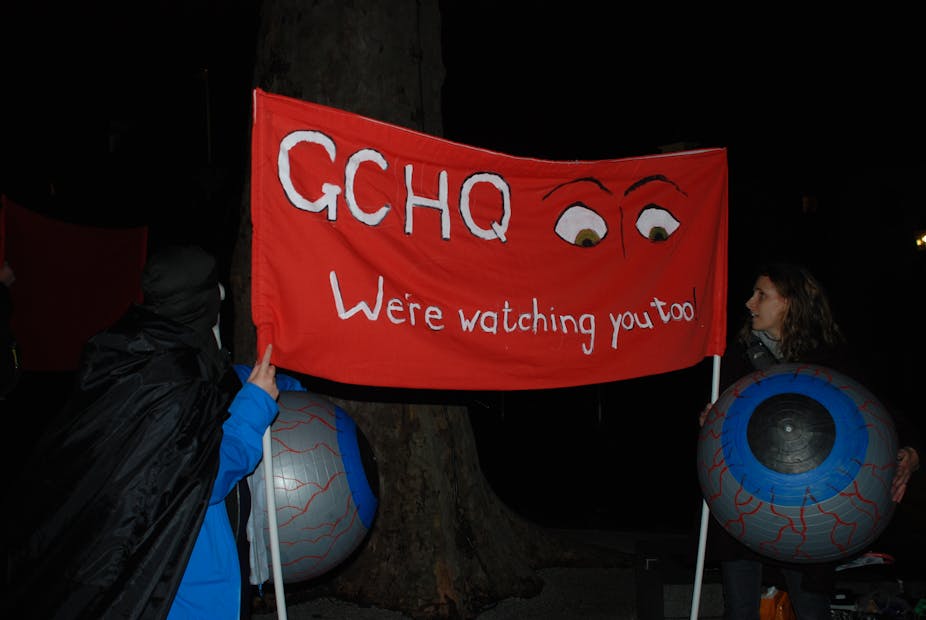

A debate is brewing after a report submitted to MPs suggested that GCHQ has been breaking the law by conducting mass surveillance on UK citizens.

In the red corner sits public law barrister Jemima Stratford, many of the MPs who commissioned her advice in the first place and, of course, Edward Snowden. In the blue corner we have GCHQ and foreign secretary William Hague, who has argued that the agency operates solely within the boundaries of the law.

The legal provisions in question in this case are remarkably obscure. This is not because they are ancient or unusually lengthy but because, when the statutes that govern these organisations were developed, two inconsistent objectives came into play.

On one hand, the government wanted to give democratic legitimacy to an agency – GCHQ – which had been formed in utmost secrecy during wartime. On the other, they needed to hide two big secrets in plain view.

The first secret was the precise nature of the ever-changing technologies of surveillance and the vast government agencies that develop and employ them. The second was the extent of international intelligence cooperation in particular under the historic transatlantic arrangements for sharing signals intelligence with the NSA.

When torn between legitimacy and secrecy, parliamentary drafters choose terminology that is designed to obfuscate. In this instance, the grey area is to be found in the statutory definitions in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, or RIPA for short. The government is keen to point out that GCHQ acts within RIPA and its charter.

As Stratford and her co-author Tim Johnston argue in their 33-page legal opinion for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Drones, this may be correct, but the elasticity of some of the concepts gives ample scope for activities that could violate human rights.

Central to the current debate is the distinction the RIPA provisions draw between interceptions of communications warrants, which must identify specific targets for surveillance and are approved individually, and “authorisations” for interception of external communications, such as when the originator or recipient of the communication is outside the country. These external communications authorisations, approved by the Foreign Secretary, need only specify general categories of information and are then subject to less rigorous controls over the examination of material obtained. The interception of metadata is likewise subject to lighter regulation and can be undertaken by a number of public agencies, subject to the approval of a magistrate.

The legislation does contain safeguards against the use of external communications warrants as a substitute for targeted interception of internal communications. But, crucially, RIPA does not distinguish between metadata and content in a way that corresponds to current technologies.

As a result, the weaker controls over gathering metadata allow for the collection of much personal information that a decade ago would have only been available under the stricter regime. Nor does the legislation contain any effective safeguards against the transfer of intercepted material to overseas agencies such as the NSA, or deal adequately with controls over material flowing the other way.

When challenged, officials like to point out that the UK system of surveillance and oversight has been found to be compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. This is partially true but also quite misleading. The European Convention sets, at best, some rather minimal standards for surveillance and should not be the limit of parliament’s ambition in regulating surveillance.

The European Court of Human Rights has found that the legal regime in RIPA for interception of internal communications is sufficiently clear to meet the standards of Article 8 of the European Convention. It is important to note, however, that the court’s reasons were influenced by the targeted nature of internal surveillance in which warrants signed by ministers denote named persons and premises. There is nothing here to suggest that the court would approve of bulk electronic interception.

The court has also looked less favourably on GCHQ’s mass surveillance of phone traffic between Ireland and England in the past by tapping into underwater cables. Its ruling that GCHQ lacked a legal basis and violated human rights in doing this should be taken as a significant indicator of how the court might approach the current allegations being made against GCHQ over mass surveillance. If Snowden is to be believed, the equivalent procedure is still practised by GCHQ and other intelligence agencies to obtain access to internet traffic passing through key cables.

In response to the growing concern about GCHQ surveillance, ministers have offered general reassurance and pointed to the largely irrelevant warrants. Since the allegations centre on mass surveillance by GCHQ involving interception of external communications and collection of metadata, this amounts to evasion rather than a meaningful response.

The Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament came out with an initial defence of GCHQ and its practices but, in the face of mounting public concern, it has now initiated an inquiry into the adequacy of the legal regime for surveillance. At least it is asking the right questions, even if the government continues to duck them.