The recent closure of illicit drugs website Silk Road by the FBI has been hailed as a decisive blow in the fight against organised crime and another victory in the global War on Drugs.

Although a minor player in the international drugs trade, the sudden closure of the site and the arrest of alleged mastermind Ross Ulbricht sent a shockwave through the online world. Silk Road users, many of whom had grown complacent after years of uninterrupted trading, were rudely awakened to the risks associated with online drug distribution.

The latest FBI operation is a significant result for the world’s law enforcement agencies, which had long been embarrassed by the brazen online drug operation. However, is the shutting down of Silk Road going to make the public safer from the harms caused by illicit drugs?

Unfortunately, it seems, the answer to this question is almost certainly no. In fact, there are good reasons to suggest that the closure of Silk Road may actually increase the many dangers associated with illicit drugs.

One of the major concerns about Silk Road was that it enabled an unprecedented ease of access to illicit drugs, supposedly making a drug score as easy as buying on Amazon. As anyone who has used Silk Road knows, this is an overstatement. In order to source drugs on Silk Road, potential buyers first had to overcome a range of time-consuming and complex obstacles.

These obstacles included having a computer and a sufficient technical proficiency to access the encrypted TOR network; opening a bank account, linking this to a Bitcoin “wallet” and purchasing Bitcoins from a licensed vendor; providing drug vendors with a name and postal address; being prepared to wait days or even weeks for illicit drugs to arrive; as well as running the risk of orders not arriving if intercepted by Customs.

Admittedly, none of these obstacles were impossible to overcome, but nor did they compare with the relative ease and simplicity of buying drugs in-person from a local dealer.

So why were people prepared to go through all of this rigmarole in order to source drugs from Silk Road? A key answer is quality control. The thousands of sellers registered on Silk Road were each ranked according to user feedback, which came in the form of consumer comments and a rating out of five stars.

Top vendors often provided additional information, such as detailed chemical analysis of their products. This allowed consumers an unprecedented level of choice and control over the potency of the drugs they wished to purchase. While certainly not a perfect system of quality control, it was undoubtedly superior to buying a random pill from a stranger in a nightclub.

Vendors on Silk Road were also able to offer higher quality products than those generally available on the street. Online drug distribution removes many of the middlemen involved in conventional drug supply chains. Instead of having to pass through the hands of various traffickers, wholesalers and retail level dealers, drugs purchased on Silk Road could be posted directly from producers to consumers.

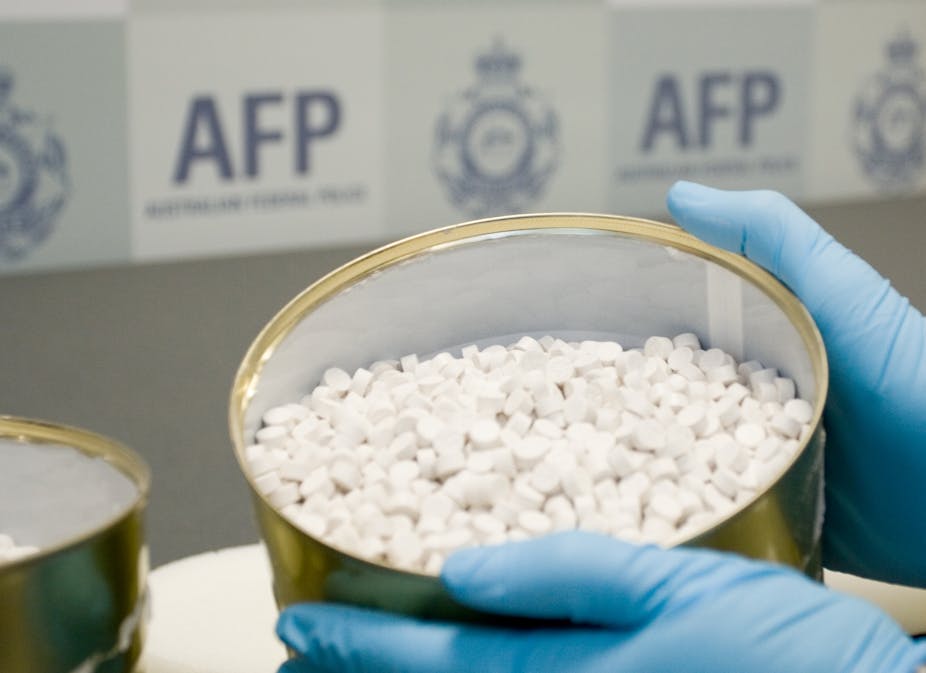

In terms of quality, this is significant because each link in a drug supply chain has a strong incentive to maximise its profit by adulterating or “cutting” drugs before selling them on. Adulteration is one of the major reasons that consuming illicit drugs is so dangerous – drug users usually have little idea of what they are actually taking.

The mid-levels in a drug distribution chain are also dangerous because this is the stage at which much of the organised violence associated with the drug trade is concentrated. Organised crime groups such as outlaw motorcycle clubs, trafficking syndicates and street gangs use violence against one another in order to control local drug markets. They engage in predatory standover tactics and turf wars, with innocent people often caught in the cross-fire.

Unfortunately, it is these organised crime groups who will benefit most from the closure of Silk Road. That is, until other illicit sites grow and assume Silk Road’s central role facilitating online distribution. In the meantime, supply of illicit drugs will be re-routed back into the usual criminal distribution networks, inter-gang violence will continue, and drug consumers will be left without a system that provided some indication of the quality and potency of the goods they want (and thereby also offered vital knowledge about safer levels of consumption).

The closure of Silk Road is undoubtedly satisfying payback for law enforcement agencies galled by an international drug operation which had achieved worldwide fame and notoriety. But it will do nothing to make our streets safer as drug consumers and their money are pushed back into the seedy underworld of conventional dealing.

Conventional drug distribution, characterised by violence and “dirty” products, seems a vastly poorer alternative to better understood illicit drugs arriving quietly and anonymously in the post. As with many of the so-called “victories” in the War on Drugs, the closure of Silk Road ultimately bears the hallmarks of short-sightedness and harm maximisation: one step forward, two steps back, and more blind progress on the road to nowhere.