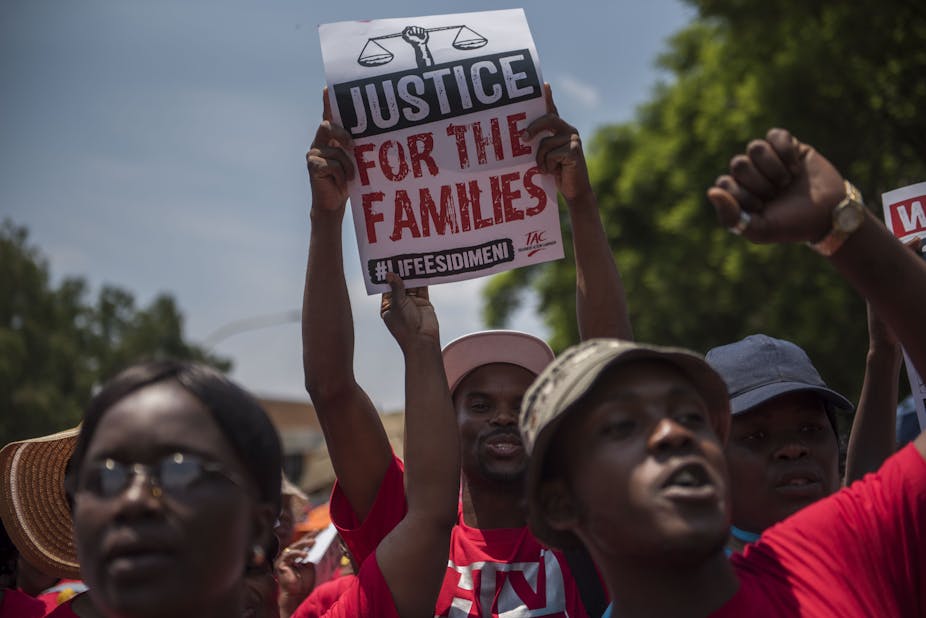

Between March and September 2016, nearly 2000 mental health care users were discharged from a private long term care facility after a South African provincial government organ cancelled a contract. Patients with varying mental health care needs were transferred to unlicensed nongovernmental organisations. It led to 144 deaths. Later, the public would hear details of how patients were deprived of basic provisions such as food, shelter and medication. Five years later no criminal charges have been instituted. On the eve of an inquest into the deaths, Jo-Mari Visser unpacks how the system has failed to bring justice.

When did the system first fail those who lost their lives?

Right at the beginning – the point at which various medical officers recorded causes of death on the death certificates.

First some context.

In South Africa, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) is the government agency responsible for instituting criminal prosecutions and performing related functions. Included is the duty to help give effect to the provisions of the Inquest Act 58 of 1959 when a death due to unnatural causes has been reported to the South African Police Service.

The NPA decides whether there is any reason to get more information or to begin criminal proceedings. But this never happened because the deaths were recorded as natural.

Here’s how the process works. When the police investigation into an unnatural death has been completed and all information, post-mortem reports and witness statements have been included in the case file, it is submitted to the public prosecutors at the NPA. The Authority studies the contents of the file and decides whether there are any outstanding investigations still to be concluded. If so, the prosecutor will return the case file to the police with careful instructions about what must be done.

If the prosecutor is convinced that, on the face of it, there is enough potential evidence to secure a successful prosecution and there are no clear reasons not to prosecute, they will institute criminal proceedings against the suspect on behalf of the state.

But if the prosecutor is not convinced of the strength of the case they will submit the case file to the inquest court. This might happen if there’s doubt about the exact cause of death or if there is not a clear link between a known suspect’s actions and the fatal outcome.

The 144 mental health care users were failed from the get-go. Immediate police investigations into these deaths were prevented because the cause of death was indicated as “natural causes” on the death certificates.

Because of this, no postmortem examinations or other forensic investigations were conducted at the time.

This affected every subsequent development.

How did the tragedy unfold?

By mid-2016, the Health Department of the Gauteng Province – South Africa’s economic hub – had implemented its decision to cancel its contract with the Life Esidimeni Health Care Centre. This resulted in more than 1700 patients being moved haphazardly to other hospitals and non-governmental organisations. This was despite warnings that such a move would be detrimental to the patients’ well-being.

Almost immediately reports of abuse, starvation, dehydration and neglect surfaced, and by September 2016, a reported 77 patients had died under suspicious circumstances.

Under public pressure, the Minister of Health instructed the Health Ombud of South Africa to investigate the circumstances surrounding the deaths. In a comprehensive report published in February 2017, the ombud detailed the unacceptable – and often horrific – conditions in which the patients were moved and cared for after their removal from Life Esidimeni.

The report showed that almost all aspects of the move and subsequent care violated the National Health Act and the Mental Health Care Act. It also violated the patients’ and their families’ constitutional rights to, among others, dignity, life, access to quality health care services and environments that are not harmful to their health and well-being.

The report also revealed the entries on the death certificates. But it made clear in its findings that “natural causes” did not reflect the circumstances in which these mental health care patients died.

The entries on the death certificates came under scrutiny again some time later during a dispute resolution process between the families of the deceased patients and the government, a restorative process recommended by the ombud. Former Deputy Justice Dikgang Moseneke oversaw this arbitration process.

In his arbitration report Moseneke recorded the concessions made by the state that

the deaths of the concerned mental health care users were not natural deaths but caused by the unlawful and negligent omission or commissions of its employees…

He attributed blame to the former Gauteng MEC for Health who cancelled the contract with Life Esidimeni, several provincial governmental officials, and the staff of the NGOs who carried the same legislative and constitutional duties of care as the state toward the patients and their families.

But Justice Moseneke stopped short of ordering the police to investigate criminal charges against the mentioned parties. He rightly held that the police must perform their investigative functions as the law commands it, and not at his bidding.

By this time, SECTION27, a public interest law centre, had assisted some families of deceased patients to submit requests with the South African Police Service to launch inquests into these deaths. By the time the arbitration was concluded, all 144 case files had been submitted to the NPA.

Despite the NPA’s fervent investigations it found that not enough evidence existed to justify the institution of criminal proceedings. Insufficient evidence about the exact cause of death and the connection of specific role-players to these deaths resulted in the NPA submitting the case files for joint inquest in 2021.

What good will the inquest do?

An inquest is not a trial. No pronouncements on guilt will be made and no person will be named “accused”.

The purpose is to fill those evidential gaps that preclude the NPA from instituting criminal proceedings. During the inquest, each piece of evidence will be perused, more evidence will be collected and all possible avenues will be scoured to find answers to the questions: how did the patients really die? And who exactly caused their deaths?

It is important to remember that while the health ombud and arbitration assigned blame to certain entities and individuals, criminal proceedings are conducted on a much higher standard of proof. Potential evidence will be subjected to strict rules of admissibility and must carry sufficient probative value to persuade a criminal court of the guilt of specific perpetrators - beyond reasonable doubt.

But this reflects the second great failure in the process of pursuing justice for the deceased and their loved ones. The police investigations and forensic examinations of most of the deaths only started during and after the arbitration. It is not known how much time had elapsed between the deaths and the performance of autopsies once it was determined that the deaths were not – as initially indicated – due to natural causes.

Even less is known about any opportunities the South African Police Service and its Forensic Division should have had to collect crucial evidence during the time immediately following the deaths. We will never fully understand how much evidence has been lost due to these failures.