In recent years, the start of Kenya’s electioneering period has often been marked by a wave of resignations by men and women seeking high office as required by law. It’s no different this year as the country prepares for another election in August 2022. Four Cabinet secretaries and at least 13 of their assistants have so far resigned. Ambassadors, as well as board members and chief executives of state organisations have also quit their jobs to seek elective posts.

Kenyan law requires public officials seeking political seats to resign at least six months before a general election. In the private sector, there is no time limit. However, many aspirants are forced to leave their jobs alongside their public sector peers if they hope to keep up with them on the campaign trail.

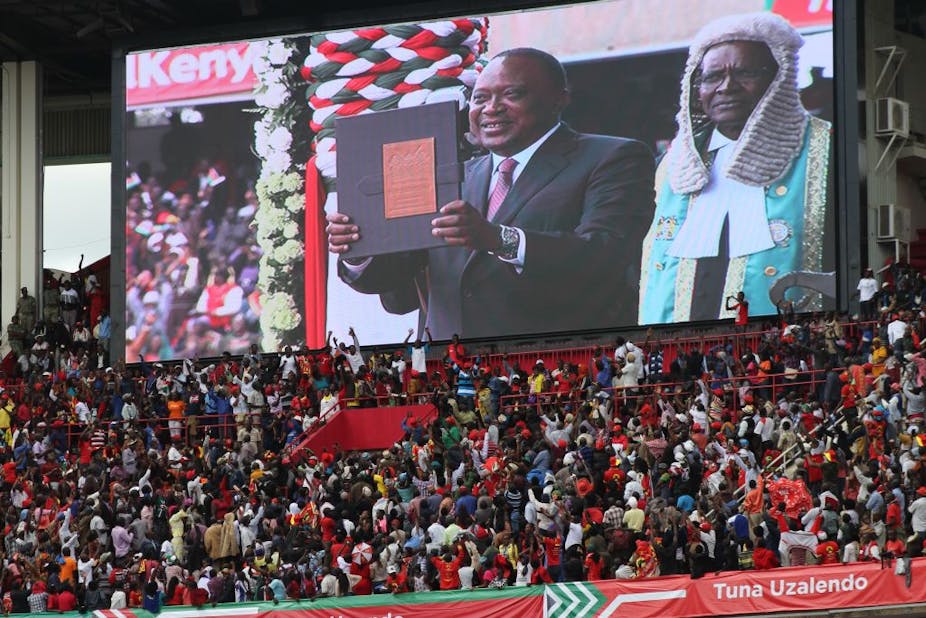

Kenyans will enter the ballot box to elect six representatives at once. They will be able to mark a cross for: the president (jointly with his deputy), the governor of their county, a senator, a woman representative, a member of parliament (MP) and a member of a county assembly (MCA).

Before devolution in 2010, the ballot paper included only three elective posts: president, MP and councillor.

In total, the country elects one president, 47 governors for each of the 47 counties, 47 senators, 47 woman representatives, 290 MPs and 1,450 MCAs. More senators, MPs and MCAs are nominated depending on political party strength in the country’s senate, parliament and county assemblies.

Why would ministers, or Cabinet secretaries, seek elective posts? Have Kenyans suddenly fallen in love with serving citizens? What is the attraction in political office when national leaders have such complex problems to solve, including rising debt, high unemployment and the aftermath of COVID-19?

Using an economic lens and collating academic research on this theme, it seems the factors pulling people into politics are diverse. However, there are some common threads.

Professor of political psychology Joanne M Miller’s research has found that:

people higher in socioeconomic status are most likely to become active in the political process because they have the time, money, and/or civic skills necessary for participation.

That explains the resignations to some extent. Slowly and surely, Kenyan politics is becoming a preserve of the few elites – the rest are spectators. This is perhaps one of the signs that Kenya has come of age; it is behaving more like a developed country.

These countries tend to have a well-crystallised elite that controls power and wealth. As a result of elite schools, intergenerational wealth transfers and capitalism, a few people are in charge despite all the praises heaped on democracy.

Over more than 20 years while working in Kenya and the US, I have analysed politics in Kenya through an economic lens and witnessed these shifts. Most Kenyans aren’t aware of the unintended consequences of the patterns of power that favour a few. That includes the impact it has on democracy.

The pull factors

Becoming a politician in Kenya is financially very attractive. The salary paid to politicians, plus other fringe benefits like car, house and travel allowances, offices and lifetime pension, are often too good to pass up.

Add allowances for membership to committees, and the perks that go with that. There are also club memberships, security details and the prestige of being called ‘mheshimiwa’ (Swahili for honourable, or your excellency).

Read more: Kenya: why elite cohesion is more important than ethnicity to political stability

There’s another factor that could be driving the interest in political power. It is likely that the money going to counties from the national government will increase from 15% of the country’s total revenue to 35%. In the July 2021 to June 2022 financial year, counties were allocated Ksh370 billion ($3.3 billion). This amount will more than double if the disbursement to counties is increased.

For some, this is a good enough reason to get into politics – to follow the money where it can be found, ostensibly to serve society. The truth is often different.

What is the other attraction beyond financial perks? Kenya has few alternatives to heroism beyond politics. The country rarely honours doctors, engineers and other professions. Politicians, however, are always in the headlines. They are a reference point in major decisions in the country.

Additionally, Kenya has few adrenaline-filled events, such as exploring the moon and the solar system. Politics remains the only arena where we can size each other up.

It’s also possible that those shifting to politics believe they have nothing to lose. They have reached the apex of their careers and trying something new that is more exciting is the next step.

Politics is like an addiction; rarely can you stop someone from joining. Politicians and potential politicians see only possibilities. They create their own reality that’s hard to change.

Lots of politicians will burn their fingers after failing to get the title ‘mheshimiwa’. But from this, Kenyans can hope a new generation of politicians will emerge, driven by altruism, love for humankind and intergenerational thinking.