A drop in the number of secondary school students learning languages in UK schools is fuelling concerns about the country’s global competitiveness, particularly after Brexit. Discussions among both politicians and the media centre on the worry that the UK is being held back globally by its poor language skills. The UK economy loses roughly £50bn a year due to a lack of language skills in the workforce.

British Council and British Academy reports all critique modern foreign language (MFL) teaching in the UK. They also express concern about the lack of learning in state schools compared to independent schools and the widening gap between disadvantaged children and an internationally mobile elite. It is well acknowledged that there is a need to move beyond relying on English as a lingua franca.

In line with this, Chinese, an emerging key world business language – and widely predicted to be key to UK business post-Brexit – has become a foreign language option for some UK students in recent decades. Teaching is beginning to thrive across schools and universities as a principle modern foreign language.

Cultural capital

Unsurprisingly, private schools – recognising the language as a new source of cultural capital – were the first to offer the new subject. But some newly established schools, especially particularly poor and disrupted schools in the state sector, have also shown interest in featuring Chinese in the school curriculum. They have been able to do so due to the Confucius Institute programme and the related Confucius Classroom programme initiated by the Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban) in 2004.

The Confucius Classroom program partners with UK secondary schools or school districts to provide teachers and instructional materials. The costs of such programmes are shared between Hanban and the host institutions (the UK colleges, universities, schools or school districts). By adopting Chinese as one of the taught languages in the curriculum, disadvantaged British schools hoped to indicate to parents that they provided something special and ambitious.

Owing to this, 13% of UK state schools offered Chinese in 2015-16 (and 46% of independent schools). An increasing number of students of diverse linguistic backgrounds are learning Chinese. But there are some significant issues with current teaching.

A showcase

The main reason for this is that UK schools tend to offer the language as a showcase in order to attract external funding and to enhance school profiles. Because of this, students’ long-term motivation is hard to maintain – and so is the effort and commitment of the schools.

Trawling through various school policy documents, I found that Chinese is perceived as a difficult language that only favours talented and able students. Because of this, little effort is made to develop these courses. And as a result of this short-termism, there is little attempt to improve teaching methods.

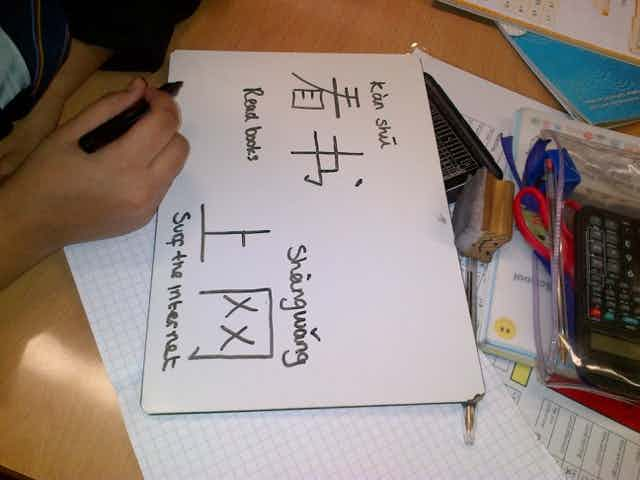

One way to develop sustained interest in students would be to teach students more about the Chinese culture and to learn the language in a cultural and communicative context. Some basic teaching of Chinese history, geography and cultural values do feature on the curriculum, but the cultural tradition is largely restricted to traditional customs and stereotypical Chinese symbols such as landmarks, festivals and food. This leaves no room for any cultural knowledge of the modern Chinese society, modern music and other areas that would help develop the interest of UK students and build connections.

Provision and resources

Chinese is very isolated in most modern foreign language departments. Severe competition takes place for students and for resources. This means that Chinese is not given adequate time in the curriculum. The language is more demanding – in the sense that it is fundamentally different from English and the Roman script – and Chinese teaching therefore requires more hours, more strategies and resources to make it equal, easy and accessible to all students. But the teaching hours given to Chinese in most state schools are less than French, Spanish and German, if the language is offered at all.

As a result, many schools – constrained by limited resources and exam orientation – select pupils for the course from the very beginning or cut down student numbers at GCSE level. The language can be made less difficult and less boring only when the class is given more hours and more resources.

Only when there are adequate provisions, good teaching practices and a whole series of supportive policy in place, can the Chinese language serve as a new source of cultural capital that might empower UK students of all backgrounds. This will be especially important after Brexit. And without action from government in terms of school policy and curriculum development, ensuring equality of opportunity and achievement will be hard to meet in such a competitive and increasingly globalised world market. Schools and teachers cannot do it alone.