Across Australia, the rate of imprisonment has climbed by about 25% in the past decade, over a time in which the rate of offending has dived 18%.

How can it be that we have less crime but more people in prison?

It’s the conundrum at the heart of a Productivity Commission research paper released this morning entitled Australia’s Prison Dilemma.

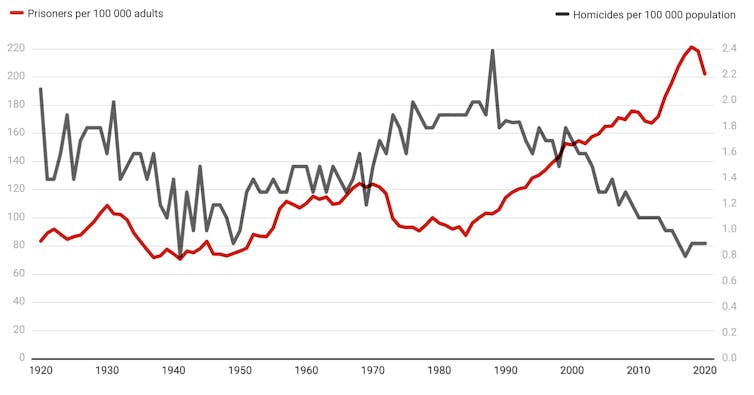

This graph presented in the report uses homicides as an indicator of trends in the incidence of violent crime because almost all homicides are reported to police.

Homicides and imprisonment per 100,000 Australians

The apparent fall in imprisonment during the pandemic may not last. It appears to be due to COVID-related decisions to release more unsentenced prisoners on bail, and slowdowns in court processing during lockdowns.

Competing explanations

One obvious – but incorrect – explanation for rising imprisonment at a time of falling crime might be that rising prison numbers are deterring crime. But the best evidence from Australia and overseas shows little if any such connection.

Another might be that “tough on bail” laws are leading to more people being held in prison awaiting trial. Even if some are later found not guilty or are not sentenced to prison, such a change could push up prison numbers while total crime is falling.

Or it might be that “tough on crime” policies are making us send people to prison for crimes that previously would have led to a fine or suspended sentence.

Or we might have increased sentences – imposing more time for the same crime.

Our research finds the correct answer is “all of the above”, with the key driver across Australia being changes that are “tough on crime”.

Read more: Australia's prison rates are up but crime is down. What's going on?

The biggest drivers of increased prisoner numbers across Australia are the chance that a person who is found guilty is imprisoned and the length of the term.

Both have been increased by new policies that mandate prison sentences for certain crimes, eliminate suspended sentences, and make it harder to get parole.

Toughness is understandable

The changes might be appropriate. Perpetrators of violent crime can destroy lives, and they make up almost 60% of the prison population.

However, a lot of prisoners have committed more minor offences with little risk of harm to others. Over one third of prisoners have sentences of less than six months and 60 per cent have been in prison before.

Many of the repeat prisoners are stuck on a treadmill of prison, minor crime, prison with untreated drug or alcohol problems, untreated mental illness, and few if any employment prospects.

Locking up low level offenders just to have them churn through prison again and again is costly.

Toughness is expensive

On average, we find imprisonment costs taxpayers about A$120,000 per prisoner per year.

That’s about $5.2 billion in total.

We find that if Australia’s imprisonment rate had remained steady, rather than climbing for twenty years, the saving in prison costs would approach $13.5 billion.

And we find that if we could focus on alternatives for just the 1% of prisoners who create the least risk to society we would save about $45 million per year.

Australia already uses alternatives.

Among them are home detention with electronic monitoring, and diversion programs where offenders receive community-based treatment for their addiction or illness.

The alternatives are cheap

These alternatives save money. Community corrections programs cost one-tenth of prison terms.

They can also lead to better outcomes, for both the offender and for society, by getting prisoners off the prison-crime-prison treadmill.

They do heighten some risks, but a careful choice of the offenders offered the alternatives along with strong supervision using modern technology, and the knowledge that prison awaits those for whom the alternatives don’t work means the risks can be kept small.

Adopting these alternatives requires evidence about what works and buy-in.

The existing evidence base is poor. Our report highlights a range of evidence-based alternatives from here and overseas, but many are never evaluated.

The alternatives need to be fair and just – not only to the offenders but also to the victims. But for low-level offenders caught on a prison-crime-prison treadmill, “tough on crime” means “tough on the taxpayer”.

We ought to be able to do better.