Mozambique has one of Africa’s lowest electrification rates. The national grid reached just 23% of the population in 2012. Around 68% of Mozambicans live in widely dispersed rural areas making extending access to electricity difficult. The national grid infrastructure is extremely limited and increasingly struggling to cope with rising demand.

Around 80% of the country’s residents rely on biomass resources like wood, charcoal and leaves as their sole energy source for cooking and heating. Ironically, this widespread energy poverty is happening against the backdrop of plentiful natural resources. In the past decade, significant coal and gas resources have been discovered.

The wealth generated by this extractives boom represents a significant opportunity for Mozambique. It could provide the chance to address long standing challenges around limited electricity access and widespread energy poverty. Electricity needs to be sustainable, accessible and affordable to all. It should not be the sole preserve of industrial consumers or those in urban areas.

The politics and economics of electrification

The Mozambican state has increasingly prioritised the extension of the grid to rural spaces. Yet this effort has left the country with a critically under-maintained network. There is also a heavy reliance on a single energy source, hydro power. Administrative, transmission and distribution losses – totalling 27% of power generated – exacerbate the country’s increasingly acute energy shortage.

Mozambique’s electricity quantity and quality deficit could emerge as the biggest constraint to continued economic growth. Rural electrification projects are thus heavily backed by donors who see them as a promoter and enabler of economic development. What is rarely discussed with clarity is who and how many will benefit from rural electrification.

Complex financial and technical considerations are involved when extending a grid. This includes the cost and difficulty of extending the network across vast distances and varied landscapes. Yet it is also very much a political and economic process. It involves choices around tariffs, subsidies and which areas to electrify and when. Such decisions have an impact leading up to local and national elections.

The overstretched state owned energy utility Electricidade de Moçambique (EdM) has been the subject of considerable political interference and exploitation. Some of its technicians have also been implicated in corruption.

Electrification has thus become a source of business for private companies connected to Mozambique’s elites. Many of these firms have been awarded contracts without competition or with little transparency.

Decentralisation and renewable energy off-grid

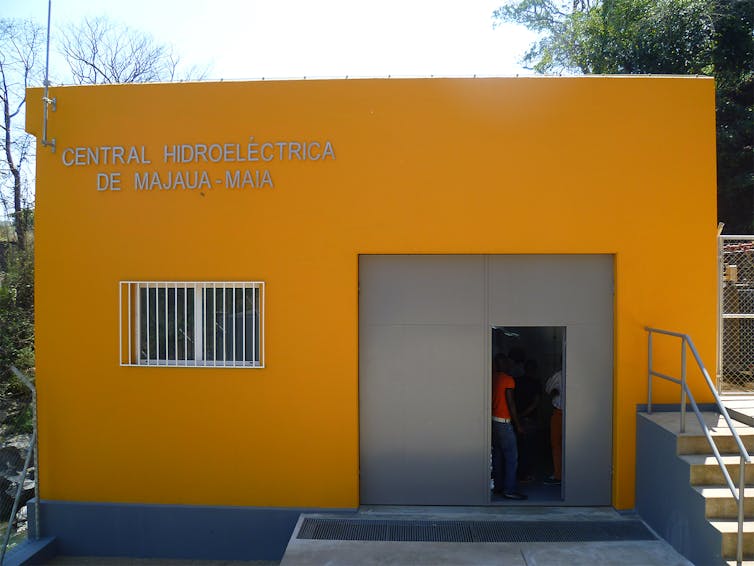

In the past few years the state has been increasingly supportive of decentralised energy projects. This is seen as the most effective way to extend rural electricity access given the high costs and complexity of grid extension. These initiatives include mini-grids supplied by solar energy or micro hydro-power.

Such measures are viewed as a small-scale solution with potentially positive distributional and environmental effects. There is little expectation that renewable energy sources alone will universalise electricity access. Or eliminate energy poverty for that matter.

Since the early 2000s, renewable – particularly solar – energy has been included in projects using localised mini-grids or standalone systems. These projects seek to provide electricity for administrative centres like hospitals, clinics and schools. This process has been led by the state’s National Energy Fund.

Our research suggests that this model has so far succeeded in expanding electricity access in far-flung rural areas. The problem is that it is often undertaken with little capacity building. Local communities are also not always consulted properly or given a chance to participate in planning and implementation.

The fund’s approach is typically top-down. It relies heavily on state procurement and donor funding. It’s focused on the centralised delivery of electricity. It also focuses on connecting rural institutions. Typically it has often been more concerned with raising the number of connections than with understanding how energy matters in people’s daily lives.

Democratising energy access

There is a pressing need to democratise energy access using off-grid, decentralised power generation. This would enable communities to have greater control and sovereignty over energy. The country also needs to reform and develop its key energy institutions.

The challenge is not the predominantly technical one of expanding generating capacity. This is how it is often presented by state agencies and donors. Rather, it lies in developing and coordinating state institutions and orienting policy to deliver electricity to those who need it most. Open public debate about what and who energy is ultimately for is a necessity.

Our research highlights the value of community engagement in designing and developing rural energy projects. This approach helps to foster greater local ownership. It will also empower ordinary Mozambicans and impart important skills. This is an essential step in ensuring sustainable energy access for all.