The celebrated Oxford-educated cannabis smuggler, Howard Marks – aka “Mr Nice” – is no longer with us. He devoted his early career to international cannabis trafficking (mainly into the US), which eventually brought him a 25-year prison sentence and then later success as an author and raconteur.

But, at least as far as the UK is concerned, Mr Nice represents the past. Since his enforced retirement from trafficking, there have been big changes in the UK cannabis market.

Before the millennium, there was a slowly expanding British market for traditional, low-potency, imported cannabis resin and herb, often originating in south-east Asia and imported through the Netherlands. All that has changed in the past 15 years. Surveys suggest that cannabis use has declined steadily since 2002 and is currently around 40% below its peak.

The nature of the product has changed, too. Evidence from chemical analysis of seized samples suggests that around ten years ago there was a large increase in the market share of high-potency sinsemilla, with the average content of the main psycho-active component D9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) approximately doubling from 6% to 12% between 2002 and 2008 in samples tested by the Forensic Science Service.

Most striking is the change in production and supply of cannabis to the UK market. The supply side of the drug market is much more difficult to observe statistically than the demand side. Drug users in the general population can be located by random sampling and many are willing to report their drug use in properly anonymised surveys.

But drug dealers are fewer in number, harder to locate and much less willing to answer questions. Most of our information about supply comes as a by-product of enforcement action and may therefore tell us as much about police priorities as about suppliers’ behaviour. Nevertheless, a striking picture emerges from published data on seizures – a move away from imports in favour of UK production.

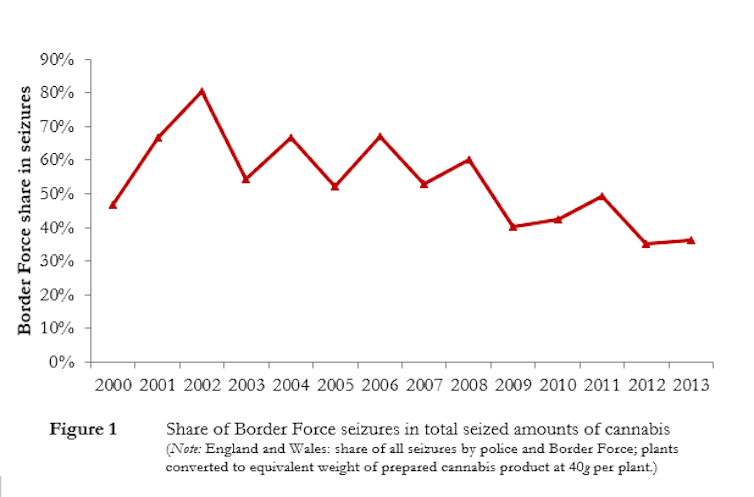

Figure 1, above, shows the proportion of cannabis seized by Border Force (who have primary responsibility for policing imports) as opposed to that captured by domestic police forces, falling from more than 70% in 2000 and 2001 to only 35% in 2011 and 2012.

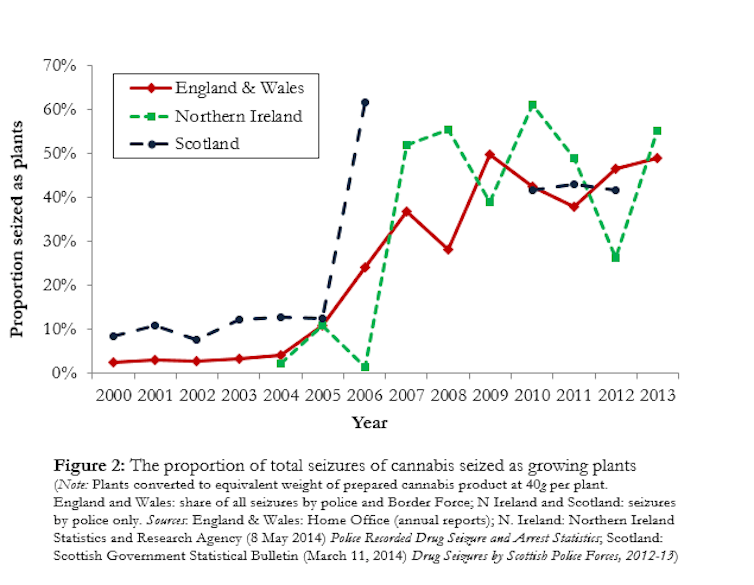

Figure 2, below, shows the trend in the proportion of seized cannabis which is seized in the form of growing plants. Imported cannabis is almost always in the form of prepared products rather than growing plants, so the trend suggests that, in all countries of the UK, there was a very strong rise in UK-based production – and that the rise happened in the space of a very few years (around 2004 to 2007).

Why did this enormous change in the nature of the market happen, and why did it happen so quickly? I don’t think we really know. Technology has undoubtedly played a role. The internet has made seeds and growing equipment much more readily available over the last decade or so and they can be acquired without the risk of imprisonment linked to importation of the drug itself.

Home-grown highs

The press has sometimes painted lurid pictures of an influx into the country of Vietnamese gangs, resorting to human trafficking to recruit “farmers” and using violence as a standard business tool. But the supposed reason for this sudden influx of foreign criminals has never been made clear and arrest statistics show a large majority of white northern Europeans involved in production.

There is little doubt that there has been increasing commercialisation of UK-based supply. The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC, formerly ACPO) reported a doubling of detections of commercial cannabis “farms” (involving cultivation of 25 or more cannabis plants or use of specialist equipment) between 2007 and 2012, with some evidence of involvement of organised crime operating across multiple production units.

Howard Marks was a lifelong proponent of cannabis legalisation, arguing that a legal market would avoid the social costs that currently accompany the production of cannabis in the UK. While I don’t think his career justifies the heroic status some have ascribed to him, it’s just possible that he was right about cannabis policy.