Music is central to my training and career as a musician and (ethno)musicologist. I’ve studied music of one kind or another since the age of four, and so I have many favourite albums and artists. But one special album - Tribal Voice - has shaped me so much more than any other, and set the course of my life and work.

It was the brainchild of Yothu Yindi, a band with roots in the former Methodist mission town of Yirrkala on the Gove Peninsula in northeast Arnhem Land. This is a remote part of Australia with an Indigenous majority population that comprises the traditional homelands of the Yolŋu people.

Formed in 1986, Yothu Yindi brought together three Yolŋu musicians from Yirrkala whose upbringings had been steeped in traditional culture - the late M Yunupiŋu, Witiyana Marika, and the late M Munuŋgurr - with three “Balanda” musicians whom they’d befriended in Darwin - Stu Kellaway, Cal Williams, and Andy Beletty. The band’s debut album, Homeland Movement (1989), opened with four original songs. What ensued, however, had never been heard on a rock album before.

The following nine tracks were drawn from song series of the Manikay tradition, the sacred songs performed by the Yolŋu at public ceremonies. Different sets of these Manikay items belonged to the Gumatj and Rirratjiŋu clans, of which Yunupiŋu and Marika were respective members. They stand as sacred expressions of their unbroken lineages from the original ancestors who named, shaped and populated the Yolŋu homelands, bestowing ownership of these myriad countries upon people of their descent.

Tribal Voice, the band’s second album of 1991, showed a much more blended approach, and produced two hit songs through remixes of Treaty and Djäpana: Sunset Dreaming (released on an extended edition of the album in 1992). This album interspersed Manikay items of the Rirratjiŋu clan, Dhum’thum (Agile Wallaby) and Yinydjapana (Dolphin), with originals sung in both English and Yolŋu-Matha. Many of these originals were influenced by themes, lyrics and direct musical quotations drawn from the Manikay series of the Gumatj clan.

Both My Kind of Life and Hope reference native honey, which is both a source of nourishment and a symbol of knowledge in Yolŋu tradition. Maralitja: Crocodile Man establishes the Gumatj clan’s descent from Maralitja, the Saltwater Crocodile ancestor, while Dharpa (Tree) sings of the law given to the Gumatj by the ghost ancestor, Ganbulapula, for hunting Red Kangaroo.

Mätjala (Driftwood) celebrates the importance of the traditional yothu–yindi (child–mother) relationship between the Rirratjiŋu and Gumatj clans, and Yunupiŋu sings of his own late father and mother, as personified by the Gapirri (Stingray) and Baywara (Olive Python) ancestors in Gapirri (Stingray).

Mainstream and Djäpana: Sunset Dreaming were both influenced by Yunupiŋu’s work as an educator of Yolŋu schoolchildren during the 1980s. Mainstream stems from Yunupiŋu’s views on the rights of Yolŋu to be educated biculturally in both English and Yolŋu-Matha, and sets forth his vision for an Australia in which Yolŋu and Balanda can live and work together in harmony and mutual respect.

His ideas were inspired by the traditional concept of Ganma (Converging Currents). This comes from a river site on the Gumatj homeland of Biranybirany where saltwater and freshwater currents meet, and produce a yellow foam on the water’s surface. The foam is referenced in the song’s first verse. Djäpana: Sunset Dreaming, the first song composed by Yunupiŋu in 1982, quotes the Manikay subject of Djäpana (Coral Sunset), which is associated with sorrow and woe.

Together, these songs offered hope and strength to generations of Yolŋu people who had been raised under the shadow of a bauxite mine on the Gove Peninsula. They offered audiences elsewhere a rare insight into the resolve and aspirations of an Australian Indigenous people.

Parents of the band’s Yolŋu members had been central to fighting a case opposing the Gove Peninsula mine in the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory. Ultimately, it failed in 1971 to recognise the continuing sovereignty of the Yolŋu people over their own homelands. The involvement of Yunupiŋu’s brother, Galarrwuy, in attempting to rectify this injustice by calling on the Australian Government to make a treaty with Indigenous peoples of the NT during the 1988 Bicentenary was immortalised in the song, Treaty. The bravery of these acts, perhaps more than anything else, is what inspired me to devote much of my career to working with Yolŋu music and musicians.

The music video for Treaty includes news footage of then Prime Minister Bob Hawke attending the 1988 Barunga Festival, and shows the preparation of the Barunga Statement, the document that called upon the Australian Government for a treaty.

Treaty also quotes a song drawn from Yolŋu history. It is not, however, a Manikay item, but rather an original song in the playful and exuberant Djatpaŋarri style, which was popular as a form of entertainment among young men at Yirrkala from the 1930s and 1970s. Its incorporation into Treaty informs the melodic structure of this song. Yothu Yindi dedicated Tribal Voice to three past Gumatj masters of the Djatpaŋarri style, and framed the entire album with two historical Djatpaŋarri songs, Gapu (Water) and Biyarrmak (Comic).

My favourite song from this album, however, is its title track, Tribal Voice: a rousing call to action. It links the plight of the Yolŋu to that of peoples all over the world who are fighting for the survival of their traditions. With repeated calls to “Get up, stand up”, it viscerally captures the ethos of resistance against oppression originally proclaimed by the Wailers in Jamaica in 1973.

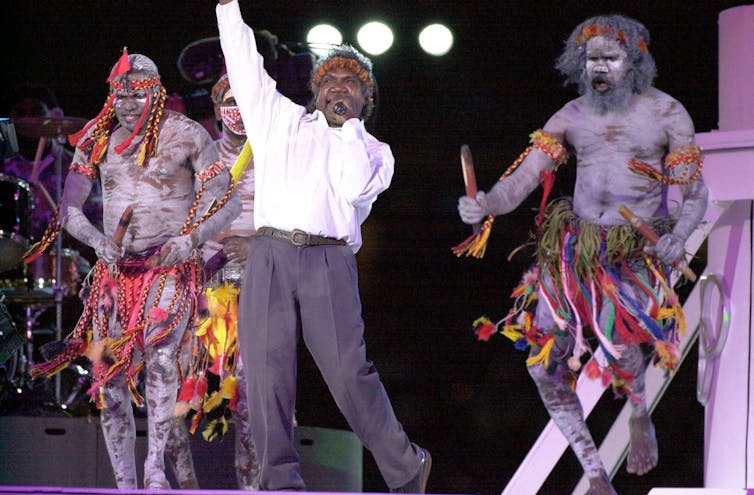

The music video for Tribal Voice is equally as powerful. The band dances amid a grove of sacred cycad palms in ceremonial dress before they are then seen touring the world against iconic landmarks including the Colosseum and the Statue of Liberty. Yunupiŋu sings surrounded by sacred Gumatj flames, and then in the cycad palm grove, his arms outstretched in Saltwater Crocodile stance.

The action soon moves to a gathering where Yunupiŋu’s brother, Galarrwuy, sings Manikay over two reclining boys being painted in readiness for initiation, which the Yolŋu traditionally perform as a garma (public) ceremony attended by men, women, and children. During the same scene, Yunupiŋu holds a ceremonial woven basket in his mouth and dances Stingray to express the tremendous power of ancestral law.

The song concludes in a crescendo of its repeated hook line, “You’d better listen to your tribal voice”, as Yunupiŋu shouts out the names of his and related Yolŋu clans: Gumatj, Rirratjiŋu, Wangurri, Djapu’, Dhalwaŋu, Dätiwuy, Maŋgalili, and Gälpu.

Tribal Voice is a tour de force. It set forth a vision for an Australia in which Indigenous peoples can live in harmony and mutual respect with their fellow citizens, while continuing to practice sacred laws and care for country in their traditions of their ancestors.

Over the past 25 years, it has influenced the topics that I’ve chosen to research, the career I’ve chosen to pursue, the friendships I’ve made, and the places to which I’ve travelled in ways that were inconceivable to me before. It has been a catalyst in my life, and in the lives of my close family and friends, which has transformed our worldviews and our understandings of what it is to be an Australian.

I will be forever grateful to the many Yolŋu musicians, including Witiyana Marika and the late M Yunupiŋu, who have collaborated with me so generously over many years and whose families have been so welcoming.