The Catholicism of the Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy has attracted some attention this week against a backdrop of fascinating political developments in Scotland. For there is plenty of evidence that people of Irish descent have been to the fore in the near-quadrupling of SNP membership to 92,000 since the referendum, which threatens to undo Labour at the 2015 UK general election.

Within weeks of the referendum, Glasgow had a near five-fold rise in SNP membership and nearby Motherwell and Coatbridge had six-fold increases. These are the heartlands of a community once defined by deep Catholic loyalties. Their neighbourhoods are shared with people who adhere to a Protestant culture, but they are less likely to have been at the crest of the SNP wave. According to one poll, just 31% of non Catholics backed independence compared with no less than 57% of Catholics.

Converts to the cause

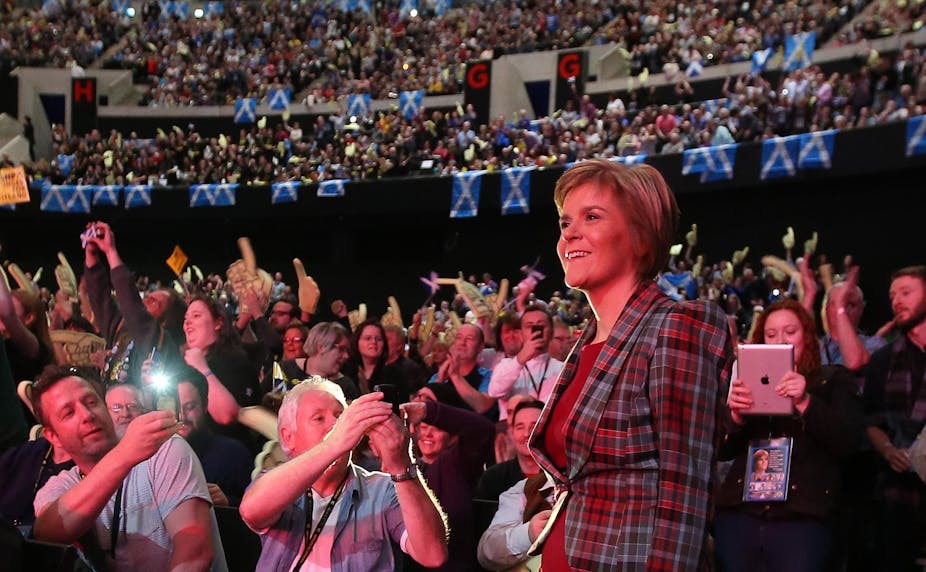

Many of these Catholic SNP converts were likely to have been among the 12,000 people who packed the Hydro arena in Glasgow on November 22. The event has been described as being like the birth of a “megachurch” rather than a conventional political rally, in which new members were inducted into the political faith. Alex Salmond, the departing leader, preached a rousing sermon and anointed his successor, Nicola Sturgeon, amid great fervour.

Scotland’s Catholic community, to which I belong, has often felt itself to be a perennial underdog at the hands of a frosty establishment. But now these Scots are mainstream. Their sense of grievance, anti-imperialism and touchiness are traits that chime with plenty other Scots.

Yet many Scots Catholics were for a long time at ease with Britishness. Their poverty had been alleviated by post-1945 British reforms. Jobs became less scarce as the state became a major employer. In 1979 most of them voted No or abstained in the first referendum on devolution.

The Catholic church has long ceased to be an effective opinion former – a charge that could equally be levelled at most denominations, of course. It has been supplanted by left-wing agitators, celebrities, mocking comedians and restless academics and journalists. They urged the Catholic community to spurn caution and embrace risk-taking without explaining how a largely low-income group would fare in the face of depleting oil reserves, the retreat of British state jobs, and an ageing population relying on a tax base over 12 times smaller than the present UK one.

During the referendum campaign, cult-like Yes rallies in Glasgow housing estates were conventions of zealotry (I attended my fair share, but the Scottish media mainly overlooked them). People with dormant grievances and minimal interest in politics suddenly became passionately intense in expressing a new faith and displaying impressive knowledge about English wickedness all the way back to 1745.

Soapbox Murphy

This is what arguably the only figure prepared to take on the cult of Yesism at the climax of the referendum discovered. Jim Murphy took his soapbox all over Scotland, holding 100 meetings in the campaign’s last 100 days. He spelled out the risks of partitioning Britain with so little elementary homework having been done. Despite being a Roman Catholic, some of his roughest receptions were in places with deep Irish associations such as Motherwell.

If he was engaged in a contest for the hearts and minds of Scots with a Catholic upbringing and some Irish roots, he failed: Glasgow and its environs voted decisively Yes. But he may have swayed enough members of the community to prevent a complete swing to separatism.

As the new leader of Scottish Labour, Murphy will certainly hope to bring disaffected voters to their senses by challenging what he sees as the dangerous impracticality of nationalism. This means that Catholic electoral areas can expect to see divisions in the UK and Scottish elections of 2015 and 2016. They are more likely to be within a splintered and increasingly post-religious community rather than between Orange and Green factions. If any Irish politicians warned these people about the risks of independence, he would likely be told to mind his own business.

The cosmopolitan outlook which membership of a vibrant world faith gave to Scots Catholics is fading. Leading bishops have drawn close to the SNP in the hope that they can influence it in matters crucial to church life, in what must be painful for Labour. Yet just like this makes it ironic for a Catholic to be ascending to lead Scottish Labour, the SNP is now being led by a flinty secularist.

And many in Sturgeon’s party have rather different views from Archbishops Tartaglia in Glasgow and Cushley in Edinburgh about when the sacredness of human life begins and ends and how far the state should micro-manage the individual. One example would be the decision of the NHS in Scotland to end the right of Catholic staff, such as mid-wives, not to participate in abortions – it is currently the subject of legal action; Sturgeon never saw fit to intervene during her time as health minister. A second example would be the Named Person Act, which requires every Scottish child up to age 18 to have a guardian appointed by the state – to huge opposition from churches including the Catholics.

We may be seeing social volatility on Clydeside harnessed and turned it into a powerful weapon. Some will see this as the acquisition of belated self-confidence by a submerged community. Others, myself included, glimpse the triumph of a new form of passivity skilfully managed by the ruling centre.

More election successes are sure to follow. But the stridency of folk shedding their religious skins and looking for a substitute faith is unlikely to reconcile them to the rest of the Scottish nation. It would indeed be ironic if this Hibernian invasion of the SNP proved the wake-up call that reinforced the determination of many other Scots to strain every sinew to hold the union together.