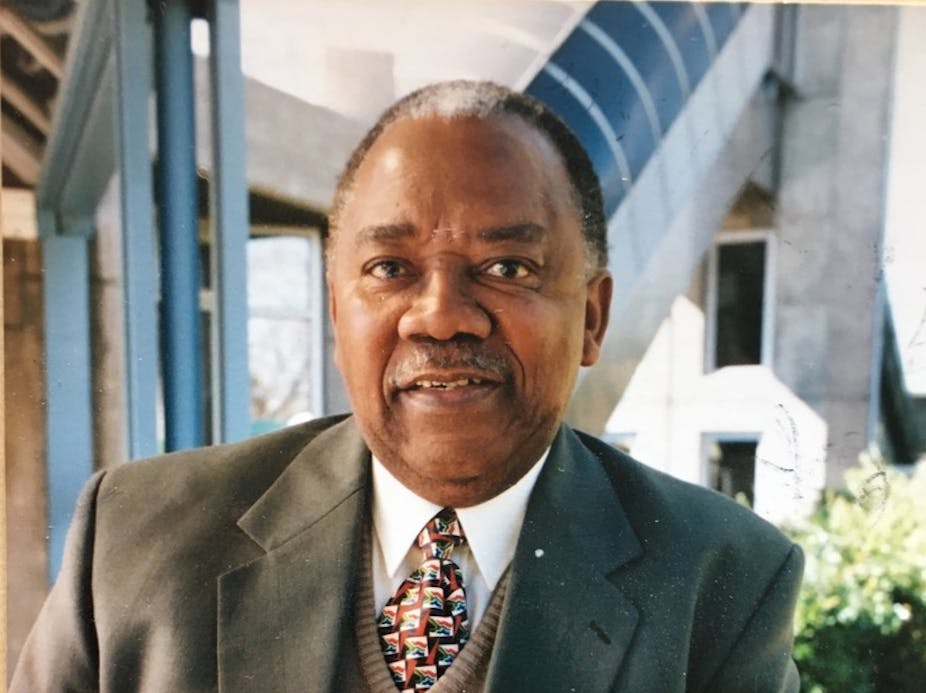

A composer of great stature, Professor James Stephen Mzilikazi Khumalo (1932-2021) stands out for his contribution to South African arts and culture. He was a distinguished teacher, a professor of isiZulu, a prolific composer with bold works that broke the compositional mould of his predecessors, contemporaries and possibly an entire generation after him.

With a compositional career that stretched upwards of four decades and an equally illustrious academic career, Khumalo received numerous awards and honorary doctorates in recognition of his stellar artistry in composition, language and the creative disciplines in general.

It is reasonable to enquire curiously about who he was and to explore the influences that made up his phenomenal success.

Composer, linguist and more

Khumalo was born in kwaNgwelu in the northeastern reaches of what is now the KwaZulu-Natal province on 20 June 1939. His parents, Andreas and Johanna Khumalo, were in the ministry of the Salvation Army. Later, the family moved to rural KwaHlabisa, where he attended school.

While one might not fully conjure up the music culture in his parents’ congregation, the Salvation Army is known for its marching brass bands and American congregational music. Perhaps his music orientation can be attributed to this background. Further, his life as a young person in the heart of rural kwaZulu in the 1930s and 1940s must have exposed him to a significant body of local musical styles.

Khumalo also grew up in different parts of the country, further exposing him to diverse languages and cultures. In an interview with the academic George Mugovhani, he reveals that the family moved to Vryheid and later to Venda in the northern part of South Africa. They then moved to Soweto, the largest township built under apartheid for black people. He matriculated from Fred Clark High School, a Salvation Army boarding school in Nancefield. He pursued his teaching diploma at Bantu Normal College, Vlakfontein, a part of what is now called Mamelodi in the east of Pretoria.

Read more: Mzilikazi Khumalo: iconic composer who defied apartheid odds to leave a rich legacy

Composer and linguist aside, Khumalo also conducted the Salvation Army choirs the Peart Memorial Songsters and the Soweto Songsters.

He occupied prominent positions in the music industry too. He was deputy board chair of the music rights body Samro. There, he also chaired a committee that edited and produced South Africa Sings Vol 1-3, a choral repertoire. The team carefully selected compositions by black choral composers and set them in dual notation, tonic solfa and staff. Brief biographies of the composers are given as well as notes on aspects of notation and correct performance practice.

He was also a member of the anthem committee notably with musicians Jeanne Zaidel-Rudolph, Richard Cock and other personalities active in the creative disciplines. Together, they merged Nkosi Sikele’i Afrika and Die Stem to establish the new national anthem of the post-apartheid dispensation.

Khumalo is highly esteemed as a pioneer composer of the epic works UShaka kaSenzangakhona, the first Zulu opera Princess Magogo ka Dinuzulu and the arrangement of the song cycle Haya Mntwan Omkhulu (Sing, Princess) which is based on the songs of Princess Magogo.

Collectively, these works placed Khumalo on a pedestal and brought him to global attention. This is the Khumalo of “firsts”: a Zulu secular cantata with soli, chorus and orchestra, a song cycle based on songs of a Zulu princess, an opera dramatising the life of the same princess. Importantly, all these are significant bearers of historical memory, heritage and Zulu vocal traditions.

What’s less known

Yet it is a slightly lesser known aspect of Khumalo that I want to focus on – the germinal seeds and the roots that bore this great talent.

Before the compositions, growing up in kwaHlabisa, Khumalo sang at weddings. Traditional weddings consist of fierce singing competitions between the groom’s and the bride’s entourages. These are festive occasions with a particular style of music quite unique to them. In fact, some of the izitibili (action songs) which are popular in choirs take their repertoires from this social milieu.

I propose that it is from this cultural knowledge learned through communal singing that Khumalo recognised the moving power of these songs. He would later arrange and add some of them to the repertoires performed during the Sowetan Nation Building Massed Choir Festival. The songs Akhala Amaqhude Amabili (two roosters cried) and Sizongena laph’emzini (we will enter the homestead) are two prime examples.

Khumalo also conducted choirs in his church. Across South Africa, black churches do not only sing hymns during services, but also amakhorasi (choruses). These are improvisatory songs characterised by synchronised movements by the congregation, often with a lead singer. A variety of percussions accompany the song and dance. Most recently, blown instruments such as whistles have been added for varied effects.

These lead to fervent moments during praise sessions in church service or other religious gatherings such as manyano (the women’s association of a church). They share qualities with izitibili (action songs) and sometimes repertoires overlap. Khumalo arranged these for his church choirs.

During his college days and early years of teaching, Khumalo formed relationships with musicians who would became influential in black choral music. One of these was Abiah Mahlase, who went on to conduct the illustrious Daveyton Adult Choir which was part of the mass choir for the premier of UShaka kaSenzangakhona.

For this discussion though, my interest is in the jazz group they formed as an extramural activity, the Gay Gaieties. Other members were Cyprian Mahlaba and Abel Dlamini. Its post college iteration had Douglas Kutumela and Solly Pelo.

Read more: Sibongile Khumalo, the transformative singer who built an archive of South African classics

All these were teachers who were prominent in choral music, especially in schools. They added traditional African music and South African black folk music to their repertoire, performing to highly responsive audiences.

Even here, Khumalo arranged some of the music. Later, they formed The Black Orpheus Folksingers, a male double quartet of teachers who were school choir conductors. Concerts had a two-part format: the first with world folk songs and the second with local ones. Khumalo added his skills in arranging in addition to being a singer himself. This set a model for schools developing an interest in African folk songs.

Astonishing versatility

I have sketched a somewhat different aspect of Khumalo’s life. I have not dwelled on the “big works” and the formal composed songs because I wished to highlight his versatility as an arranger, conductor, singer and a grassroots “worker” in the early years of his music development. I suggest it was this multiplicity of genres, subgenres and activities that he was able to adapt so deftly as he moved towards the monumental works.

It is this diverse palate that fed his musical imagination as he established himself as a Zulu, African, Pan African, cosmopolitan composer.

On 22 June 2021, Professor James Stephen Mzilikazi died, at the age of 89. South Africa and the world at large remain richer because of his legacy.