Download the full interview with Dr Chamitoff as a podcast by clicking here.

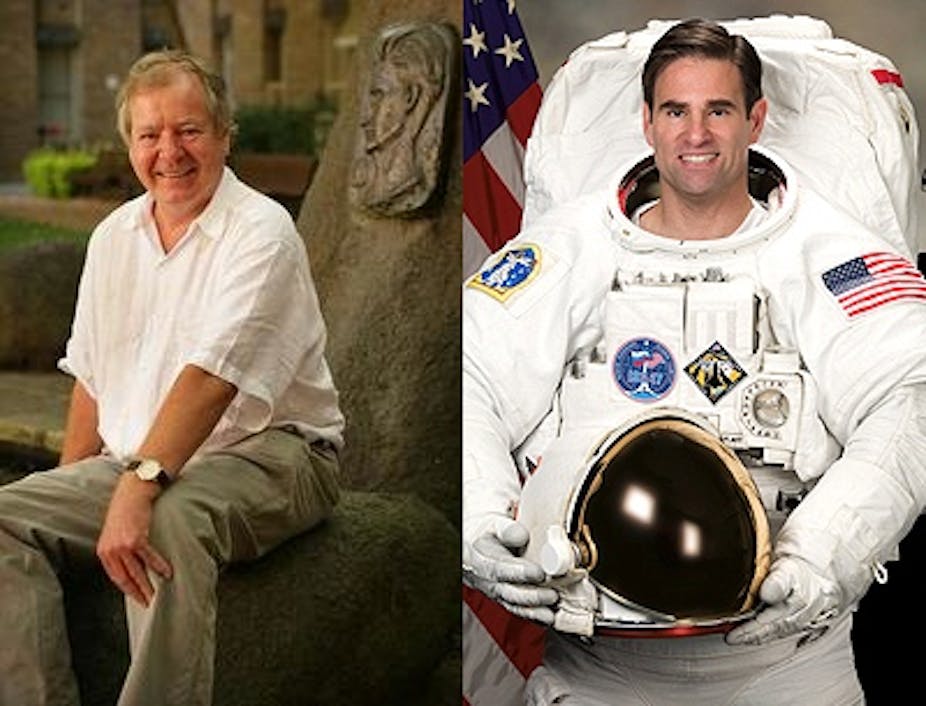

For the latest in our In Conversation series, Malcolm Walter, Professor of Astrobiology at the University of New South Wales interviewed NASA astronaut and adjunct professor at the University of Sydney, Dr Greg Chamitoff.

In May, Dr Chamitoff was a Mission Specialist on the penultimate mission in the Space Shuttle program – the final flight of Endeavour.

To date, he has spent nearly 200 days in space.

He is in Australia as a guest of the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies.

This candid, in-depth interview took place yesterday in the Mechanical Engineering building at the University of Sydney, and touches on several themes, including:

- Becoming an astronaut

- The end of NASA’s Shuttle Program, and resultant loss of jobs

- Future manned and unmanned missions

- The need for a commercial space sector

- The scientific potential of the International Space Station

- International collaboration in future space endeavours

Malcolm Walter: How is it that you became an astronaut in the first place – is it something you always dreamed about doing?

Greg Chamitoff: Yeah, it is. My kids right now are six and I now have a concept of what’s in the mind of a six-year-old. I was six years old when I decided I wanted to do this, and that was at the time of Apollo 11.

My family took a summer vacation down to Florida, and it just so happened that the Apollo 11 launch happened while we were there, so I got to see that up-close.

I grew up with a dad who was a space fanatic – we watched Star Trek together all the time and it was a funny thing because William Shatner – Captain Kirk – is from Montreal, as I am, and was from the same district, according to William Shatner, who I finally got to speak to at one point.

So my dad knew of him, which was really strange because as I kid I was like “well, there’s this Star Trek thing and I know it’s a story but, hang on a second, my dad knows that guy!”. So there was something real about it.

Dad was very fascinated by the whole space program. I remember seeing mission control, and thinking “how do people get those jobs, they would have to be the coolest jobs in the world”.

So I grew up with my father’s enthusiasm for the space program and then I saw the launch of Apollo 11 and that was it: I had to do that.

Walter: That would have been amazing to see. I saw the Apollo 11 launch on television – I stayed up all night to watch it, but I was a bit older than you …

Chamitoff: The next leap from there was the first launch of the Shuttle [in 1981]. I was in college – a freshman, first year – and I saw the launch and thought to myself:

“I’m at the beginning of college – now’s the time to figure out what to do, if I’m really serious about this”, and so I called NASA and asked them: “What do I have to do to do that?”

It’s amazing because many years later the same person I spoke to that day was on the interview board for astronaut selection.

Walter: You say you called NASA but NASA’s a vast organisation. You don’t just pick up the phone and call NASA …

Chamitoff: Nowadays it would take you two seconds on the internet to work out who to call but back then you had to do a little bit of hunting to figure out who to speak to.

Walter: It worked, obviously.

Chamitoff: One more thing that was really neat and unexpected was at university graduation. The graduation speaker turned out to be Hoot Gibson, a Shuttle pilot, and I didn’t know that was coming.

I got to walk up to the front to receive some award and, you know how they have the dignitaries sitting there?

I walked from the podium in the wrong direction, toward those folks to shake Gibson’s hand and I got to remind him of that while being interviewed many years later.

That was one of those inspirational points that got me on track.

Walter: But then you went to graduate school at MIT, didn’t you?

Chamitoff: Yeah, so I was an undergraduate at California Polytechnic, a state school, and then I did a year at CalTech for a masters and then I went to MIT for graduate work after that.

Walter: … and that was Astronautics and Aeronautics?

Chamitoff: Aeronautics and Astronautics, and that department had a history of people going from there to the astronaut program.

I was just excited about space and in those days there were only a few places where you could study spacecraft systems, and just the list of courses alone was inspiring: spacecraft altitude dynamics and control … I saw that course and thought: “I’ve got to go to a place that teaches that”.

There were a lot of great classes but now, of course, those courses are available in many more places.

Walter: And you’ve continued that sort of work: robotics, automation of various systems – you’ve used that expertise since then.

Chamitoff: Yeah. I came to Sydney for a couple years – 1993 to 1995 – and I taught flight mechanics and flight control.

After that, I went to Houston and worked in mission control for three years, on the mission control system for the International Space Station (ISS).

There were students I worked with on thesis projects, just as I did at Sydney Uni, but as a technical adviser rather than an academic advisor, and that was great. I was able to keep my head in the academic work.

Walter: So you were at Sydney University full-time were you, for two years?

Chamitoff: Yeah, that’s right. In this very building.

Walter: There’s still a lot of work going on in the Robotics Centre here, which is a very big organisation and very highly regarded.

Chamitoff: It is. One thing I was able to do on the Space Station, that I was actually a co-investigator for, was space robotics.

There was some automatic path-finding optimisation with avoiding obstacles that we did here, in Sydney, when we were trying to work on autonomous aircraft, autonomous vehicles.

We decided to apply that strategy and those algorithms to free-flying space robots, and so I got to do that while up in the Space Station, working with the people that built them. So that was pretty cool.

Preparing for launch

Walter: Tell us what it’s like sitting in the Shuttle, waiting for the launch. Most of us would find it impossible to imagine, and even harder to cope with.

What’s the feeling like when you’re up there at the pointy end, ready to go?

Chamitoff: It’s very emotional. It’s a dream come true – for most people there it’s a lifetime dream come true and it’s amazing because it comes true in a moment.

There’s a moment that you’re not sure you’re going, and then there’s a moment where, yes you are.

Walter: And it’s too late to do anything about it.

Chamitoff: And that “too late” is several days before that. There’s this machinery there – and I hope we see a day with that kind of machinery again – but there’s this huge machinery where everything moves to the launch; and, as you can imagine, the details and the different things that all have to happen …

You feel like you’re on a train and you’re not getting off at that point – it’s many weeks before the launch that you’re already on the train and you can’t get off.

And you think to yourself: “OK, the decision was made a long time ago – there’s no turning back now”.

But when you’re sitting there on that rocket it’s a very substantial kick when the rocket boosters go.

I always joke around about it because there are Disneyland rides like that, and they’re much worse, because they’re trying to impress you with all the shaking and the rocking and rolling, whereas the Shuttle is trying to do it as smoothly as possible.

There’s a certain amount of shaking but actually, it’s quite smooth compared to what I expected.

Walter: Is it hard to breathe?

Chamitoff: At some points you go up to three Gs but you’re on your back – the force is this direction, through your chest – and that’s not a problem.

It’s only difficult because it’s for several minutes, so you have to work hard to breathe but we do training up to eight Gs in centrifuges, for Russian training anyway – compared to that, it’s nothing.

When you’re up at eight Gs and they back it down to three, it’s like: “Thank God” – you feel great. Three Gs really isn’t that bad.

Walter: It takes about eight minutes to get to orbit doesn’t it? It’s not long.

Chamitoff: About eight and a half minutes. It doesn’t seem like it’s enough. You feel the acceleration and you know you’re speeding up but it doesn’t seem like that would be enough to get to that sort of speed. But obviously the maths works out.

Walter: I’ve only seen one launch and that was Return to Flight and Andy Thomas invited me to go and watch that and that was awesome, in the original meaning of the word.

Just amazing to watch and very emotional even to watch, particularly if you know somebody who’s up there.

Chamitoff: I knew somebody that was on that launch and that was a very emotional time for everybody involved.

Walter: I can imagine. Many astronauts come into the program after some other career don’t they? I’m thinking of Andy Thomas for example: he came from Lockheed Martin, where he’d been working for years.

Chamitoff: I would say that I’m midrange in that regard. There are pilots, there are medical specialists, scientists and engineers.

I was in the engineering category and those who don’t already have a PhD would have to have had many years of work experience before they would be qualified.

I had three years of work experience, one year after the PhD in Houston, working at Draper Laboratory – it’s a guidance and control company that’s an offshoot of MIT and we were working on the control system for the Space Station, actually, so before I came to Sydney to teach, that’s what I was doing.

And I also worked earlier for them. They supported my graduate work so I was with them for seven years.

So it’s not like I just finished my PhD because – it was a research position that went on for 30 hours a week for seven years, plus the two years here, so it was actually ten years in the field, and then I went to Houston.

I had already applied and I had already been interviewed and I spent three years working in mission control as a flight controller.

At that point the Space Station was brand new – it wasn’t flying yet, so we were developing the tools and the displays and the controls to work out: “How are we going to operate this thing?”; “What data do we need to see?”; “What commands do we need?”; and “How are we going to coordinate all of that?”

So we were building all that when I got there so I had three years of mission operations experience before I got selected.

Walter: A lot of astronauts have doctoral degrees, don’t they?

Chamitoff: A lot of them do. It’s not the path for a pilot obviously – they were selected because they are amazing pilots and for their leadership skills and other things they are recognised for in the military.

There are some who are flight engineer types who are also from the military, and then the doctors and scientists are MDs or PhDs typically, and most engineers are PhDs unless they were flight engineers.

Walter: So you’ve flown four times?

Chamitoff: It’s actually twice but it looks like four –

Walter: – because of your long stay on the ISS?

Chamitoff: Yeah. You know that movie, Shrek? We call ourselves SHRECs: Shuttle Rotating Expedition Crew Members.

So if you got to fly up on one Shuttle and come back on another, and since you weren’t part of the normal Russian Soyuz rotation, that meant you were split across two expeditions.

So it looks like I was on more missions than I was, but it’s the time that matters I think. On my first flight I had 183 days up there and that was a long time – plenty of time.

Caretaking Kibo

Walter: So on the Shuttle what was your role, on your two flights?

Chamitoff: On the first flight I was baggage. They were bringing me to the Station to stay as a station crew member so I joined the flight late – probably in the last three months before they flew – but I’m joking about being baggage.

We were installing the Japanese Experimental Module Kibo and I was really the one fully trained on it because I was going to be the first caretaker of what the Japanese saw, and see, as their first human space vehicle.

It’s very important to them culturally, as well as technically, and it’s unfortunate that it wasn’t a Japanese astronaut that was there first.

I did my best to make up for the fact I wasn’t a Japanese astronaut taking care of their spaceship.

Walter: But Japanese astronauts have flown …

Chamitoff: Yep, after me there was one, but for the first six months of the Module’s existence I was its caretaker and I took it from an empty shell to installing all the scientific equipment, getting it up and running, testing it all, running some basic science through it initially to commission, so that it was ready for the full-blown science program.

That was a big part of what I did up there. During the Shuttle mission, we installed the Module.

I was trained on everything so that if something happened and the Shuttle had to leave, as long as the Module was attached and they could go, and it might take me longer but I could get everything done – I could finish it from there.

That was a great experience and a great responsibility.

I tried to learn a bit of Japanese so at the end of the day I could congratulate them on what we’d accomplished each day and that was one third of it because the European Research Module had come up with Columbus just a few months before – this was in May of 2008 – and the difference is Columbus, because it is smaller, came up fully equipped, ready to start the science right away.

And so I came and worked on their science program immediately – I didn’t have to build the apparatus, unpack it, assemble it.

And of course the US Laboratory already had its science program up and running so I was with two Russians, but I was running all of the American, Japanese and European science.

I wasn’t the commander, but the commander left and they let me take care of the science and they helped when they were asked to.

But for a long time there, whenever there was a conversation in English, for the first four and a half months until we had a change of crew, I felt a lot of responsibility for quite a lot that was going on.

Four and half months into it there was a Soyuz that arrived and up came a private astronaut, Richard Garriott, who is an outstanding person in many ways, and he was there for a nine-day handover.

But the two Russians I was with returned to Earth and one American and another Russian came up. The American was Mike Fincke, who became the commander, so for the last part of my stay there were two Americans and one Russian.

Walter: What do you do to stay sane when you’re up there for that long, away from the family and all those home comforts?

Chamitoff: The language thing is funny. The language goes with the majority: if there’s two Russians and one American, dinner conversation is in Russian, and so I did my best to hold my own.

I had lots of training and practice, immersion training and whatever, but the commander at that time, his English was pretty good, so if I really needed to communicate something I knew it was going to be possible.

But it was funny because I didn’t realise how much I missed speaking English to somebody in proximity, so when Mike [Fincke] came up I realised I was following him around and talking his ear off: “Mike, am I bothering you?”

It was just nice to have another English-speaking person on board.

Walter: But what about your down-time? You couldn’t have worked all the time?

Chamitoff: We actually dedicate a lot of that down-time to trying to get science done, because at that time, it was part of the assembly stage at the Station and, with only three on board, it’s a lot of work – logistics work and assembly work, rearranging and installing systems and racks … That took a lot of time and there was plenty of science to do, but very little time in the schedule to do it.

Saturdays were supposedly a day off – well, you’re there. You’re on the Space Station, you have nothing better to do.

You might need a sleep-in once in a while to get a break, but you’re there and you want to make the most of that time.

So we regularly gave our whole weekend to science and then Sunday there might be some medical or house-cleaning things we needed to do anyway, but the days were full because of that. But we still had movie night.

Walter: Yeah?

Chamitoff: Yeah, on a Friday night the Russians would come on over and I’d introduce my Russian colleagues to a lot of our science-fiction movies.

The first one we watched turned out to be 2001: A Space Odyssey, and they had never seen it.

Walter: So there were a few light moments as well.

Chamitoff: Yeah, they were great guys. We had a great time.

Walter: And of course you played chess while you were on the Space Station, too …

Chamitoff: Yeah, that hadn’t been done before. First I was going to play chess against the control centres and the handicap for them was that they had to take turns moving.

So Houston, Huntsville, Moscow, Munich and Tsukuba, Japan, and also Toulouse, France, all had to take turns moving. That didn’t work out so well for them.

The Russians were very upset because they thought the Japanese were screwing up their game.

Walter: That sort of thing could get out of hand when you’re stuck up in space.

Chamitoff: The follow up to that was on the Shuttle flight I just came back from.

Even though the flight was so short, there was so much public outreach that was positive from the chess that they wanted to have an Earth vs. space match on the Shuttle flight.

So one of my crewmates tried to keep up with a game, twice a day and played until we had to shut down the computers and land. At the point the deal was that Earth would vote on who the winner would have been.

Walter: And?

Chamitoff: Well they [Earth] voted that they won, but there’s dispute about that. Maybe the majority thought that but some of the masters thought they would have picked our side if they’d had to keep playing the game.

Munchies

Walter: The other thing that people wonder about is food. Does that get pretty boring?

Chamitoff: There’s a cycle of food that repeats every two weeks or so but the variety within that cycle is really huge nowadays.

Walter: Does it taste like what you’d eat on Earth?

Chamitoff: It’s good, it’s really good. There’s a lot of variety. There are certain things the Russians have that are really good.

If you want a really good piece of meat – it’s actually canned meat but it’s really good – the Russians have that.

A lot of people eat the Russian fish too, but meat and potatoes – that’s the Russian meal.

We have a much more balanced selection: vegetables and all that kind of thing. But there’s Italian, Mexican, Chinese, all kinds of dishes – it’s actually quite good.

Walter: You’d be a bit short on salads though, wouldn’t you?

Chamitoff: Yeah, that’s right. But there are a few things, such as the fruit cocktail – it goes a long way to making you feel like you’ve had fruit.

But when a supply ship comes up and brings fresh fruit, that’s a great moment.

There was one point I remember when Sergei Volkov, who was the commander, throwing me an apple through several hatches and that was a really nice thing to bite into after a while.

Walter: So do you think you’ll be going back to the Space Station, aboard a Soyuz this time?

Chamitoff: I don’t know. As far as I know I’m still eligible for a long-duration flight, but there’s a period after a flight where you sort of don’t worry about it.

It’s a time to share our mission with the public, to travel around and talk about it, and I’m in that phase now.

Also, now that all the flights will be long-duration, the time between them is greater – they’ve got flights signed up through almost 2014 now.

The next one assignable will be in a six-month increment and they don’t need to assign that many people any more – it’s a few people every six months.

Now that I have kids that are six years old the training is very difficult in that you spend half your time for three or four years travelling and training in other countries, so that’s definitely hard on a family.

I’m hoping not to worry about it for a year, and then we’ll see.

Walter: There’s a story going around at the moment that the Russians are talking about not servicing the Space Station after 2020. Any truth to that?

Chamitoff: It’s kind of a misquote from something that was said. What they are planning to do is service it until 2020.

We’ve kind of made that agreement that we’re going to maintain the station until at least 2020, but given it’s such a huge investment from all the countries involved – 15 countries – nobody wants to stop all of sudden in 2020 if we’re still able to use it do meaningful research.

The thing we did in our flight – STS-134, the final flight of Endeavour – we put the last touches on and we’re now able to say: “The Space Station is now complete after 12 years of work.”

It’s got a six-person crew, it’s science-programmed in full now. Instead of trying to run a bus schedule while you’re building the bus terminal – now it’s ready and it’s almost a factor of ten in hours we’re able to dedicate to research now, compared to what it was when I was there.

So we want to see that science getting done for as long as we can, certainly until 2020 … but now they’re talking about 2028.

Unless there are system problems and we get into some kind of situation where we can’t fix something, there’s no reason we have to stop in 2020.

Walter: So the situation is that with continual servicing it could keep going for decades yet.

Chamitoff: Absolutely. It’s one of the amazing things about those massive solar panels. Every orbit you can count on that solar energy, as long as the solar panels are working … and there’s plenty of redundancy – we have much more than we need to maintain the station.

If we’re running a full science complement and there’s a problem with energy we might have to back off on something, but as long as the solar panels are working, in fact if half of them are working, the station will be fine.

Winning

Walter: You mentioned the science program. Is there something that stands out as a highlight in terms of science achievements for the ISS and Shuttle Program?

Chamitoff: There are a few things that stand out. There’s been a change in focus from the NASA perspective to do science on the station that’s going to enable us to go beyond low-earth orbit: the human physiology aspects, the zero-gravity, the radiation, the bone-loss.

Some of those things have applications on Earth, the bone-loss in particular – the topic’s always been there, it’s obvious, and there’s been a lot of time now to look at different countermeasures and what works and what doesn’t, and there are certainly applications for osteoporosis here on Earth and there’s been some interesting results.

One of them, around about the time I was there, was that there seems to be a sodium uptake that’s higher in zero-G and they don’t know exactly why.

It turns out that it looks like the body’s trying to control the pH in the blood and demineralising the bone to do so.

We do two hours of exercise a day up there, but even if you did ten hours of exercise every day, if the body’s fighting to control the pH in the blood, that’s a factor they suddenly realise is there.

So now there are more studies to look at that in depth.

Another one that’s somewhat recent is that they’ve been looking at organisms and their response to zero-G and it’s really surprising. Sometimes you think of bacteria in a fluid: “Why would they care which way the gravity vector is? They’re in a fluid anyway.”

But defining the behaviours of bacteria and gene expression is very different without gravity.

And things you just wouldn’t think zero-gravity would have an effect on. Salmonella was a good example.

They found over 160 genes that express themselves differently in zero-G and the result was a much more virulent organism.

I’m not a biologist so I don’t really understand the details but by recognising the genes that were causing the change, they were able to work on a vaccine against salmonella to attack those particular genes.

Walter: One of the things I’m really interested in is the physical limits of life and life can stand and, in that context, it might include the transfer of bacteria from Mars to Earth or vice versa aboard meteorites.

I’m not talking about contamination of spacecraft or anything like that, but it’s a respectable thing these days to think about the possibility that life might have started on Mars and transferred here on meteorites.

We do have meteorites from Mars that we know about, here on Earth, and there will be Earth meteorites on Mars.

You just can’t rule out that possibility now, so what you’re talking about would feed into that science as well.

Chamitoff: Well there’s another example, and maybe it’s very recent, but there was a recent result from a study where some organisms were placed outside the ISS on platforms we have for that purpose – exposing everything from circuitry, solar panels, materials, paints, protective layers, all of these things; to expose them to the radiation of space, the vacuum of space, the thermal cycle, the micrometeorite environment, to see how well they perform.

One of the European exposure facilities had some cells and they found they were still alive after being exposed to the total vacuum of space and to radiation for a prolonged time.

So that’s a new result and it validates your theory. It was the first time that was ever seen. The cells were brought back down to Earth and were still alive.

Walter: Those little bugs are hard to kill, and we know that from our hospitals – golden staph, and all that sort of thing.

Do you think the pace of basic research and development will pick up now that the Station is physically complete?

Chamitoff: Absolutely. There’s been success with muscular dystrophy and other things where they’ve been able to look at a protein and understand the 3D structure because of crystallography, and that’s an ongoing thing – looking and trying to understand the 3D chemistry of proteins and things like that.

A worthwhile enterprise?

Walter: As you’d know, there’s been a lot of scepticism about the Space Station and the Shuttle Program – has it been worth $40 billion?

Chamitoff: You could say $100 billion from beginning to end split across 15 countries – that’s a good round number.

Walter: That’s a lot of money.

Chamitoff: It is. If you’re looking for a specific result, in a specific area applied to a specific problem on Earth, then that’s a certain lens to look through.

I think the other way to look at it is this: the ISS is a unique facility in a unique environment and we now have laboratory facilities up there to look at materials science, fluid physics, biology, human physiology, exposure to space environment and Earth observations.

There’s clearly a lot we can learn there. There have been more than 1,000 investigations, hundreds of publications, and now we’re going to crank up to a much higher percentage of our time dedicated to science.

Undoubtedly there are going to be some very interesting and meaningful results.

And whether it solves a particular problem on Earth or enables us to live on Mars and colonise Mars, it’s going to be significant.

I want to mention the one experiment we brought up because on our flight we brought up the Alpha-magnetic Spectrometer.

Now that’s a world-class observatory and it’s looking at cosmic rays instead of light, which is unique among the observatories.

There are a lot of unknowns in Big Bang theory, how much matter and anti-matter there is, and where it is, and where’s all the matter in the universe – we see the motions of the galaxies but the matter doesn’t match up to the motion that we see.

So it’s looking specifically for dark matter and for anti-matter, but at the same time it’s going to be characterising the spectrum of the radiation – we don’t have that characterisation yet, and that characterisation will help to protect crews and hardware on future missions.

It’s a very fundamental science program but it’s going to have practical applications too.

Future missions

Walter: Well, let’s talk about future missions. The plan was to go back to the moon–

Chamitoff: Was

Walter: Is “was” correct?

Chamitoff: Officially, what we had going was cancelled for a new plan. Unfortunately, right now we’re waiting to find out what the new plan is still. But there were good reasons for cancelling the return to the moon.

Obama had a commission review what was going on and that was headed up by Norm Augustine, so you can’t fault the selection of who was on that review committee.

The recommendations made a lot of sense. We needed more money to accomplish what we were trying to accomplish and this vision for space exploration plan started in 2004.

It was underfunded and we ran into some problems, so the idea that we either need more money or change the direction – there was nothing wrong with that conclusion.

Unfortunately, the retirement of the Shuttle was supposed to be timed with the development of the next spacecraft, but those things got disconnected.

So now the Shuttle has been retired and we weren’t ready to launch the new vehicle on the next day, and we should have been.

So that’s where we are now. But are three prongs to where we are now. One is the Space Station: we’re still going to fly there, we’ll launch from Russia. We want to use that facility [the ISS] to the maximum and make it available to the academic and commercial industry.

We also want to develop a heavy-lift vehicle because that’s what we need to get beyond low-earth orbit – that’s a major priority.

Deciding on which vehicle we build, soon – before we lose all of our technical capability, because we’re laying people off by the thousands – that’s the major problem.

Walter: A lot of that technical capability went with the end of the Saturn V, I suppose?

Chamitoff: Exactly. And the other thing is the commercial space. I don’t think anybody would disagree with the idea that the real explosion of humanity into space, and off to Mars and colonising Mars and being able to do science on other planets – that’s all going to happen when it becomes commercially viable to operate in space.

So the idea of feeding the commercial space industry to provide us with access to low-earth orbit and access to the Space Station, there’s nothing wrong with that – it’s a good idea.

The only problem is stopping the Shuttle program while we wait for that. Now we’re grounded and waiting.

Walter: Until when, do you think?

Chamitoff: They’re saying three-to-five years. The one milestone in the short-term is the launch of SpaceX in November, taking cargo to the Space Station.

That will be great if it happens – a great first step – but I think three years is very optimistic. I think it’s probably more like five-to-seven years.

Walter: But it’d be the same vehicle but human-rated?

Chamitoff: That’s the idea, and then there are other concepts out there. One perspective is that we had a very capable space ship [the Shuttle] for getting us to low-earth orbit, to the Space Station.

It could do amazing work to upgrade, repair, fix, maintain, supply and bring stuff down from the Space Station, scientific down-mass as well as hardware.

We’re not going to have a down-mass capability like that for a long time and we’re now waiting for the commercial sector to get us back to low-earth orbit.

We were already going to low-earth orbit for 30 years and the commercial sector has to get there first, then we have to go beyond it.

Walter: So there’s going to be a hold-up in ever getting back to the moon as a result?

Chamitoff: That’s right – we’re really waiting for the commercial sector. In the meantime we’ll work on a heavy-lift vehicle.

Walter: Is that happening now?

Chamitoff: Yeah, and I think we’re just waiting for a decision as to which way that’s going to go – which design are we going to go with for the heavy-lift space launch system.

If we get that decision made relatively soon, a lot of the workforce that was recently laid off, they will come back – they’re dying to come back and work on the next program.

If it takes too long to materialise, we’re going to lose a lot of the talent, and that’s the problem: it’s such an amazingly skilled workforce.

To see the Shuttle being processed before the launch, it’s just unbelievable. To stand there in the cargo bay you go: “This is an amazing spaceship”.

And we know everything about how to do it.

Walter: But you’re losing people, as of now?

Chamitoff: We’ve lost thousands already. That doesn’t mean they’ve moved on, but soon they will.

Walter: There’s a tension between robotic exploration of further space and human exploration of space, a tension between Johnson versus JPL [Jet Propulsion Lab] – that sort of thing that people talk about.

I’ve always thought there’s an inspiration factor there in human space exploration that robotics, as brilliant as they are and as unquestionably amazing as they obviously are, just don’t quite create.

For anyone that saw us first step onto the moon, its something they’ll never forget and I’ve heard it said that the Apollo program would never have been supported by the American people if it were a robotic program – wouldn’t have been supported for so long, anyway.

Do you think that’s true?

Chamitoff: I agree with you, but I think the tension is artificial. I don’t think there’s anyone in the human space exploration side of it that isn’t absolutely thrilled about everything that’s happening in unmanned exploration – they’re just as excited.

When the Rovers landed on Mars, anyone at the Johnson Space Centre was just as teary-eyed as anyone at JPL.

But I think there’s always going to be a balance – I think you always want the robotics to go out first and go out further and we have a long way to go in robotics.

For example, if we build a facility on Mars, it’s going to be a mixture of robotics and humans working together and we’re getting a lot of experience with that already. We do it all the time on the Space Station.

We have a lot of robotics, we have humans in the loop, we also have automatic aspects to that.

As a side-note, there are new surgery tools being built based on the operation experience we have on the Station – it’s a robot but it’s being controlled by a human in the loop. That’s all developing and I think it all goes hand-in-hand.

Walter: If you look at it from a public point of view without knowing all of the inside workings, that’s where I think the inspiration comes into it and ultimately where the public support comes from.

Chamitoff: Yeah. Well there’s no story to tell of a robot on the way to Mars. There’s a story to tell when it lands and when it discovers something, but if humans were on their way to Mars, there’d be a story every day.

Walter: Is there a public perception in the US that your country might be overtaken by China or Japan or India or Europe if you don’t keep up the momentum?

Chamitoff: Yeah, I think that threat is healthy – healthy to keep the focus.

Walter: And to keep the dollars flowing?

Chamitoff: I think so. The amount that NASA has been able to spend on the space program is very small compared to other programs. Recently I saw that the air conditioning in Afghanistan for troops was more than all of NASA. The percentages and priorities are maybe not what people think they are.

But still, it’s more than other countries have been able to spend and I hope we can use those resources in a meaningful way, to keep leading the way.

The International Space Station was a really good example because one of the things that came out the review that looked at the space program was that we can’t afford to do the whole thing we were planning to do on our own.

And we didn’t build the Space Station on our own – it was very much an international, cooperative venture from beginning to end.

Walter: But very clearly led by the US, particularly in the early days.

Chamitoff: Yes, although the perspective from Russia would probably be different. We think we led, they think they led, and now there are three Russians on board and three others, two of which are American and one is often, or usually, from one of our other international partners.

But there are always three Russians on board, so I don’t know who’s in charge.

But it was very much an international effort and I think that’s a good model for peace, cooperation and for going further.

I don’t think the US should be thinking of doing it on its own – I think collaboration is a really good model.

Walter: I think it’s a really good model as well and it’s often non-diplomats – scientists, engineers and medical scientists – that keep channels of communication open internationally when times are tough.

Chamitoff: Yeah, no matter what’s going on politically, the scientists and engineers are still meeting and they’re colleagues and friends.

Walter: Do you foresee any Chinese involvement in collaborative exploration projects or Space Station projects?

Chamitoff: I definitely think it’s possible. Unfortunately it’s not a decision that can be made at the NASA level – I think if it was, we’d already be talking to them more.

It’s at the congressional level that it has to be allowed and then that will trickle down.

Walter: The Chinese seem intent on ramping up their space program as fast as possible and it’s easy to imagine them going to the moon in a few years time.

Chamitoff: Yeah, and the number of engineers they are graduating compared to the rest of the world is just staggering, and they’re hard-working, they’re goal-driven.

Walter: Things have gone a little bit quiet in Japan perhaps, but the Indians are ploughing ahead. In a way, there’s a bit of a space race again isn’t there?

Chamitoff: I hope so. I hope there’s a space race and I hope it’s cooperative and I hope industry gains a foothold, too.

Walter: Going back to one of my key interests, Mars exploration, the great plan of geologists like me is to bring samples back from Mars.

I think the joint ESA [European Space Agency] and NASA mission to do just that might be launched in 2018, all going well. That sort of collaboration would just be wonderful.

It’s often said, and I don’t know if this is true, that it just couldn’t be done without that collaboration – it’s just too expensive to be supported by one nation at one moment.

Chamitoff: Hopefully we’ll see that soon and not too long after that we’ll see someone like you, a geologist, on Mars, hammering on the rocks yourself.

As you know, Mars is amazing in terms of sites of scientific interest and the ability to use resources there.

We already have a reactor on the Space Station that utilises the carbon dioxide in Mars’s atmosphere and gets the oxygen back and makes methane which we could use for fuel on Mars but we waste on the Space Station.

We already have these recycling processes that could utilise the atmosphere on Mars, in place, already working in space and of course there’s water everywhere on Mars – in some soil, definitely in ice at the poles.

Walter: It’s a very exciting planet to explore from my point of view. We’ve learnt a lot about the formation of the solar system and I think there’s a very good chance that there is life on Mars, or at least was.

Chamitoff: And that would be one of the most important finds in human history if we found life of any kind, or fossil evidence of life on another planet.

Walter: That’s what I tell my students. I just hope I’ll live long enough to see it happen.

Chamitoff: Me too, and it happens to be the closest planet too, at least away from the sun – the direction you want to, you don’t want to go the other way.

Walter: It’s feasible to go there now isn’t it? It’s only a six-month trip.

Chamitoff: It is feasible and that’s the thing: there are really no showstoppers technologically. We can start building ships to go to Mars now – we already know how to do that.

There are some claims that radiation would be a problem but you can use water as your shield, using your water tanks in a way that protects the ship and crew.

There’s really no technological hurdles that would stop us from starting to build the hardware now so it’s really just commitment and finances.

Walter: Do you think you’re going to live long enough to see astronauts on Mars?

Chamitoff: I hope so. I had hoped I was going to be one of them but the day I realised that wasn’t to happen was 9/11.

When that happened I thought that the focus and resources in the US was going to shift too much to have Mars as a focus and keep it within my career-span.

The only way for me to get to Mars now is to win the lottery and buy a ticket 20 years from now.

Dr Greg Chamitoff is delivering a guest lecture at the University of Sydney this evening, Tuesday August 2. Minor edits have been made to this transcript in order to preserve fluency.

Please leave your comments on this interview, and any of the issues it covers, below.