A campaign to prevent a downgrade of Lewisham Hospital in south-east London was given a significant boost after a high court judge ruled that Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt and others were acting beyond their authority.

The Lewisham case isn’t just another story of reorganisation and public disapproval but a tale of natural justice and whether one trust - and hospital - should suffer for the financial mess of another.

Lewisham’s finances

Lewisham Healthcare NHS Trust is a mid-sized organisation that includes acute hospital and local community services. In 2010-11, its turnover was about £220m. It produced a surplus of about £1m in that year, having overcome recurrent deficits to achieve sustained surpluses over a relatively short time.

It epitomised successfully integrated NHS organisation: financially stable, well liked by its users, and expected to achieve foundation trust status - when trusts gain more financial independence. Then external events overtook it.

Its misfortune was to be sited close to the vast, failing South London Healthcare Trust (SLHT), which was put into administration in July 2012, with losses predicted to exceed £60m annually.

In early 2013, Hunt agreed with the administrator (Matthew Kershaw, from business adviser McKinsey & Co) that Lewisham should merge with part of the dissolved South London Trust, with the downgrading of its hospital and the closure of its A&E department. This seemed grossly unfair to everyone in Lewisham.

The closure of A&E had other knock on effects. Maternity services that relied on access to the emergency department would also need to be downgraded.

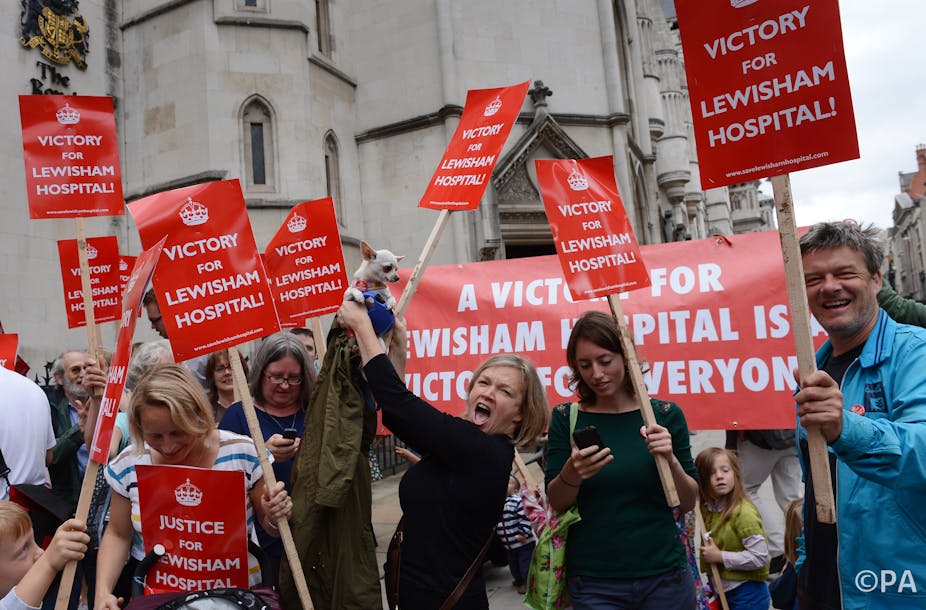

The decision was challenged legally, a judgement overturned it and the government is now considering an appeal.

The judgement is important, not only for Lewisham, but for the messages it sends out about the NHS, its drivers, controls, and self-determination.

Self-determination

Over the past few years, Lewisham has shown the value and impact of self-determination. The trust successfully overcame its financial problems, absorbed community services, and built up a reputation as a thriving, effective organisation, and a significant player in its local health economy.

If these achievements are discounted, and its future determined by Whitehall, then staff (clinical and otherwise), users, and local organisations such as the council, will all see themselves as entirely disenfranchised; how that perception is incorporated into a political agenda of “localism” poses an interesting challenge - especially as Hunt has advocated less power coming down from the top.

The high court judged the downgrade to be unlawful because Hunt and others were circumnavigating legal procedures that would have included much more consultation with the public and the local council.

Dashed expectations

The current NHS reforms in England are based on a few simple premises. The first involves clinicians in driving reforms, which gives them a sense of buy-in and responsibility and also accountability. The second is an extension of this: as GPs instigate most NHS spending through prescribing and referrals, they should be involved in strategic spending as well as operational decisions.

The Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) that are made up of these GPs and are currently finding their feet are the embodiment of this, with responsibility for around two thirds of the entire NHS £108 billion budget and some influence over the rest. In their first year they need to learn to walk (getting themselves established and their members engaged), but also to run (producing considerable savings and starting to plan future, more strategic activities).

These tasks would be hard enough, but if the application of their new found skills were to be immediately overturned by governmental dictat, then all the efforts that have been applied in overcoming GPs’ natural cynicism about their involvement will have been wasted.

And Lewisham CCG strongly opposed the proposed changes for Lewisham. If their views were ignored, it would send out the wrong message and the entire purpose of the current reforms would risk being lost. The judge also considered their position.

‘Vox populi’ and democracy

However, if the press is to be believed, Wednesday’s judgement seems to have been driven entirely by local activists trying to save their hospital. While local support is helpful, it would be bad if national policy on the welfare state - in this case the NHS - was only the result of local pressure.

There is a strong argument for reconfiguring and improving services. And while campaigners have argued the Lewisham downgrade decision wasn’t made in the interest of local health, the government and management believe it’s inevitable that changes in south-east London will come.

The NHS was designed to be both egalitarian and utilitarian and as such, strategy needs to be driven in a systematic, rigorous fashion. The recent Health and Social Care Act, which ushered in NHS reforms, suggests that decisions about service configuration should be made by CCGs working together, with appropriate input from NHS England, and under the aegis of overarching government policy.

This is what should have happened in the case of Lewisham and the South London Healthcare Trust.

In doing so, the reconfiguration exercise might have been handled better. High-level players need to be involved but preferably not the politicians; operational delivery is best left to those who know how to do it.

Patients and the public are also obviously important protagonists, but it would be a dangerous precedent if major reconfigurations were seen to be driven by individual public demonstrations.