Have you ever actually read the terms and conditions before signing up to a website or ordering something online? These long, wordy documents are a form of consumer protection designed to make sure we are fully informed when we agree to an online contract. They are supposed to ensure we are making a conscious decision to sign up to a service with full knowledge of the consequences.

But the UK’s Citizens Advice reports that even though around a third of consumers claim to read these terms and conditions, looking at the actual amount of time spent accessing them, it seems likely that only around 1% of people really do read them in full.

The reason for this behaviour is that the text is often as long as a Shakespeare play and written to be understood and used in a US court, not by your everyday internet user. The net result of this being that they are virtually incomprehensible to the average consumer. Somewhat unsurprisingly, a Eurobarometer survey found that 67% of the people who did not fully read privacy statements found them too long, and 38% found them unclear or difficult to understand.

The fact that so many people don’t fully read terms and conditions has significant consequences. If users don’t understand the implications of what they are signing up to, they may not be aware how much control the service provider is asserting over their content or the extent to which their information is being mined and traded.

For example, you might unknowingly allow a social media platform to use your photos for their marketing purposes. Or you might agree to allow a simple torch app for your smartphone to collect location and device data, which can then be sold on to advertisers. Hypothetically, you could even have a “private” online conversation about early retirement that is then sold on to parties such as credit agencies and insurance companies who use it to justify charging you more money.

Kitemark idea

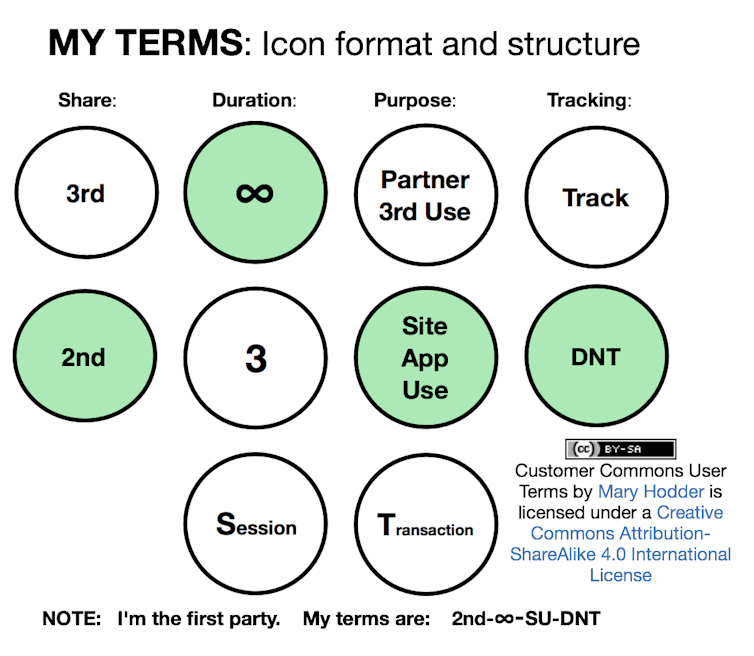

But what if there was a way to protect your data, without having to wade through those documents? A House of Lords committee recently recommended introducing a “kite mark” to identify websites that meet EU standards for handling and processing personal data. They argued that this would provide a visual symbol for consumers to know that they weren’t signing up to anything they objected to. This could even involve a traffic-light system to give an indication of what degree of data privacy protection a website offered.

The Information Commissioner’s Office is now proposing a voluntary scheme in which sector-specific, third-party operators will evaluate the legal and ethical dimensions of how companies handle personal data. Exactly who these operators will be has not yet been announced but, once they are established, companies will be able to apply to have their data handling procedures certified. Those that meet the requirements will be given permission to display a “privacy seal”, telling customers that a “trusted third party” has approved the firm’s operating practices.

As part of the incentive to entice service operators into adopting this scheme, a range of kite marks are being devised. This will differentiate between those companies that simply conform to legal requirements and those that provide their customers with extra levels of control and protection.

Much like licensed occupations or accreditation by professional bodies, the proposed kite mark scheme would transfer some of the responsibility for evaluating a company’s service away from untrained citizens. Instead, it would be put into the hands of specialised organisations with technical and legal expertise.

But there are a number of practical issues facing the scheme before it can be successfully implemented. First, there is the problem of finding a good way of visually conveying information about the complex nuances of personal data handling.

Next, there is the issue of establishing a clear and auditable procedure for evaluating data handling procedures and how to translate those into kite mark ratings. This is especially challenging when it comes to indicating not only legal but also ethical practices.

Finally, there is the burden that such a certification process might place on online businesses and the question of who would pay for it – the business or the taxpayer? A key question for online companies will be whether the cost is worth the perceived advantage gained in consumer trust.

One stumbling block to this may come from the reality that online services are dominated by US companies that look at business on a global scale, with hundreds of millions of customers. From that perspective, a UK-level kite mark initiative, affecting fewer than 60m citizens, rapidly looses its significance unless it is picked up and implemented at an international level.