The United States is the world’s largest seafood importer, purchasing about US$20 billion worth every year. It is also a global leader in seafood sustainability, with some of the world’s strongest laws and policies designed to prevent both overfishing of target species and incidental harms to other species.

One of the major global challenges to harvesting seafood sustainably is that marine mammals like dolphins, whales and sea lions are often killed incidentally in fishing operations. This problem is called “bycatch.” Bycatch is known to affect at least two-thirds of the world’s marine mammal species. It was largely responsible for the recent extinction of the Yangtze river dolphin in China, and it is pushing the vaquita porpoise toward extinction in Mexico.

On Jan. 1 the United States started enforcing a new import rule, which requires fisheries exporting seafood to the United States to protect marine mammals at standards comparable to those required for U.S. fisheries. This rule aims to leverage American market power to reduce marine mammal bycatch worldwide. It also aims to level the playing field for U.S. fishermen, who currently face monitoring costs and fishing restrictions to reduce marine mammal bycatch – unlike some of their foreign competitors.

If this rule succeeds, it could serve as a model for responsible globalization by demonstrating that countries can be competitive in global trade without “racing to the bottom” in their environmental standards. But to make this happen, the United States will have to set the right standard, work with other countries that need help to comply and possibly defend the rule in international courts.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act and the import rule

Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, enacted in 1972, federal regulators monitor marine mammal bycatch in U.S. fisheries. They also develop plans to ensure bycatch remains within well-defined limits that will not threaten marine mammal populations. If a fishery exceeds these limits, regulators can require fishermen to change their fishing gear or methods, or even close the fishery temporarily.

The MMPA is one of the world’s strongest marine mammal protection laws, and has greatly improved the status of Pacific dolphins, harbor porpoises and California sea lions. But it also has made U.S. fisheries less competitive by imposing fishing restrictions and monitoring costs that vessels in many other countries do not face.

The new rule, administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, gives countries that want to export seafood to the U.S. a five-year grace period to prove that their exporting fisheries monitor and limit marine mammal bycatch as effectively as U.S. fisheries are required to do under the MMPA. The idea is to level the playing field for U.S. fishermen by encouraging other countries to raise their environmental standards, rather than lowering U.S. standards. By benefiting both U.S. trade competitiveness and marine mammal conservation, this rule should have bipartisan appeal.

Keys to success

The key question is how NOAA will define standards that are “comparable in effectiveness” to U.S. requirements for monitoring and limiting bycatch. A low standard will make the new rule toothless and fail to reduce the number of marine mammals killed in fisheries that sell into U.S. markets. Success at the highest achievable standard depends on three factors, some of which we discussed in a recent article.

First, other countries must want to comply with the new standard, which means they must believe that access to the U.S. market is worth the cost. As the world’s largest seafood importer, the United States has a lot of market power. Pressure from U.S. consumers has already made “dolphin-safe” tuna fishing practices a near-global standard.

But if NOAA sets the equivalence bar too high – for example, requiring monitoring systems so sophisticated that they cost nearly as much as fishermen would earn from their catch – other countries may choose to sell their catch into other markets, such as China, rather than investing in new scientific and regulatory infrastructures to meet the U.S. standard.

Second, other countries must either have or be able to quickly obtain the monitoring and enforcement capacity they will need to comply. Five years is not much time for countries to gather enough evidence to show that their fisheries do not cause unsustainable marine mammal bycatch. And the longer the U.S. takes to formulate clear equivalency standards, the less time countries will have to meet them.

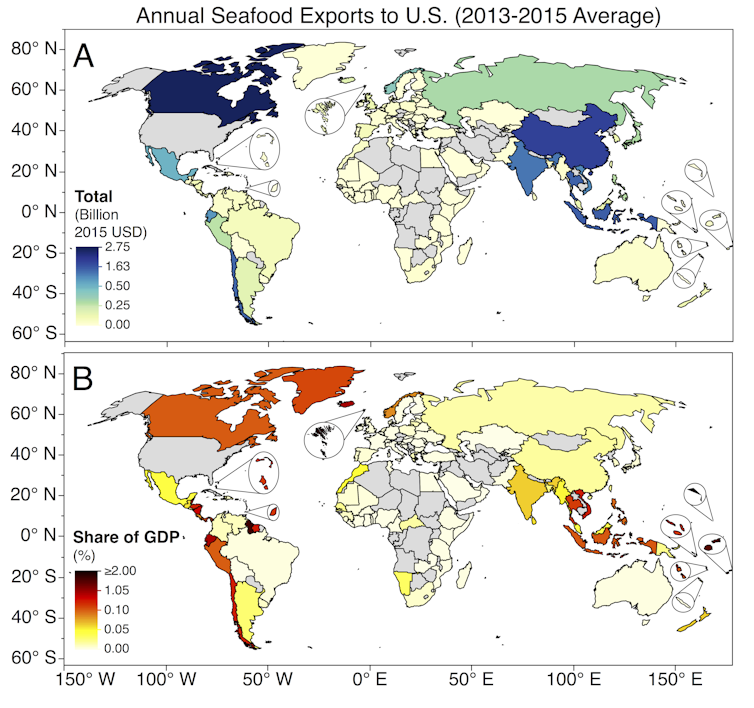

While countries like Canada, China and Indonesia export the largest quantities of seafood to the U.S., the countries that are most economically dependent on exporting seafood to the United States – and thus have the potential to be most severely impacted by the new rule – are Small Island Developing States and some small Latin American countries, such as Guyana and Suriname.

Seafood exports from each of these countries come mostly from one or two fisheries. Improving management in one or two fisheries in a small country within five years is a challenging but tractable problem. U.S. aid and development agencies and philanthropic organizations can help capacity-poor countries comply within the grace period by providing them with funding and technical advice. And since most marine mammal populations span multiple jurisdictions, countries could save resources by coordinating monitoring efforts regionally.

Third, this rule needs to be able to withstand legal challenges in the World Trade Organization and under other international laws. NOAA asserts that the rule complies with international law because the rule requires standards of effectiveness, rather than specific policies or practices. But NOAA may have to defend this assertion in international courts. Some experts are less optimistic that import bans could survive a WTO challenge.

Banning imports from some fisheries that fail to comply with the new rule could, in theory, increase prices for U.S. seafood-importing companies and consumers. But NOAA has concluded that these effects are likely to be very small. Import bans would affect only noncomplying fish products, which NOAA hopes will be few. And the U.S. imports its highest-volume import products like tuna, shrimp and salmon from many different countries, so U.S. buyers should have plenty of time to find new sources for products facing bans during the five-year grace period.

Race to the top

NOAA has taken a bold step with this rule and should be applauded. If it succeeds, the rule will demonstrate that environmental protection does not have to conflict with global business competitiveness, and that market-based incentives can maintain high environmental standards even where international treaties do not yet exist.

Businesses, labor unions and conservation advocates have warned that global trade may cause a “race to the bottom,” in which countries progressively lower their environmental, labor, taxation or corporate accountability standards to keep their producers competitive in globalizing industries. This new rule could be a rare blueprint for racing to the top.