One of the great fears for scientists is that their work will be met with derision, especially when someone has been handed a sizeable sum of money to confirm what the man and woman in the street already knows full well. You only have to look at the annual Ig Nobel awards to get the idea. Driving while using a mobile phone is more dangerous than without one. Men don’t like to go bald. We’re likely to wear more clothes when we’re cold. All of these fall within what we might call, with apologies to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the “No shit, Sherlock” category of science.

But there are often valid reasons for studies of this kind. For instance, it’s not wholly inconceivable that experiments might just show, contrary to all gut instinct and common sense, that driving while using a mobile phone is actually remarkably safe. Granted, it seems unlikely; but the point is that we can’t completely rule out the possibility. However much we think we know something, we have to be as sure as we can.

Karl Popper’s The Logic of Scientific Discovery, which championed the merits of falsifiability, is central to this credo. Popper posited that no number of experiments can ever conclusively prove a theory but only a single experiment is required to disprove it. (And people wonder why so many research papers end with a veiled appeal for further funding). So any theory that can’t be falsified by experiment isn’t scientific. It lacks evidence. It can’t be tested. It’s rooted in cosy confirmation rather than refutation.

For a more availing elucidation of the principle it’s hard to beat Richard Feynman. In The Meaning of It All, his exploration of the relationship between science and society, the winner of the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics likened scientific progress to a cascade of sieves with ever-smaller holes; a theory might safely pass through sieve after sieve before finally getting stuck – whereupon, regardless of all that has gone before, it’s time for a rethink. The philosophy of science dictates that we can never have too many sieves.

Sieving through patient safety

In 2013 I was appointed as one of the Health Foundation’s second cohort of improvement science fellows. Our task was to champion a rigorous and scientific approach to raising the quality of healthcare. And, sure enough, what we very quickly determined was that we needed some new sieves.

Until only a few years ago it was de rigueur for research into patient safety to concentrate largely on finding a technical intervention for a single setting. It was taken as read that the relationship between knowledge and practice was a linear one. Metrics, targets and star ratings clouded the picture. Problems with a multifaceted nature were afforded little consideration.

The tack changed in 2010, when the National Institute for Health Research called for studies on organisational culture, the role of the patient, the costs and financial implications of patient safety and the boundaries between elements in the whole system.

Our research into discharge procedures illustrates this crucial shift. It highlights how so many of the shortcomings in patient care boil down to a lack of communication between the many different agencies and carers involved in the care system, with those responsible for the individual elements of a system attempting to operate in isolation. A doesn’t talk to B; B never deals with C; C has mentioned his concerns to D, but D is confident everything will turn out all right eventually; E is supposed to have oversight but in reality hasn’t a clue what A, B, C and D are up to most of the time; and so on.

Context and culture

One general problem is that healthcare has an unhappy history of borrowing ideas from other industries – aviation, say, which gave us incident-reporting systems – while overlooking the embedded social, cognitive and organisational infrastructures that make them work. Solutions can’t be transferred from one domain to another without allowing for difficulties in interpretation and differences in context.

In health, “context” is incredibly nebulous and vague and has come to represent the bundled mess of complexity, economic constraint, political pressure and professional culture. Indeed, a similar story can be said of “culture” which has long been the focus of improving safety but without much detailed research or theory behind it.

Today we’re shining a much more illuminating light on the messy realities. Take, for example, the transition of patient care from hospital to a care home. A striking finding from our research was the way “hospital discharge” meant different things to different professionals. For hospital doctors and nurses it was often seen as an end-point and organised for the end of the day or week. For those in social care, hospital discharge was often the start of their involvement and usually preferred at the beginning of the day or week.

This simply mismatch could result in patients beginning transferred home on a Friday afternoon with only limited social care until Monday morning.

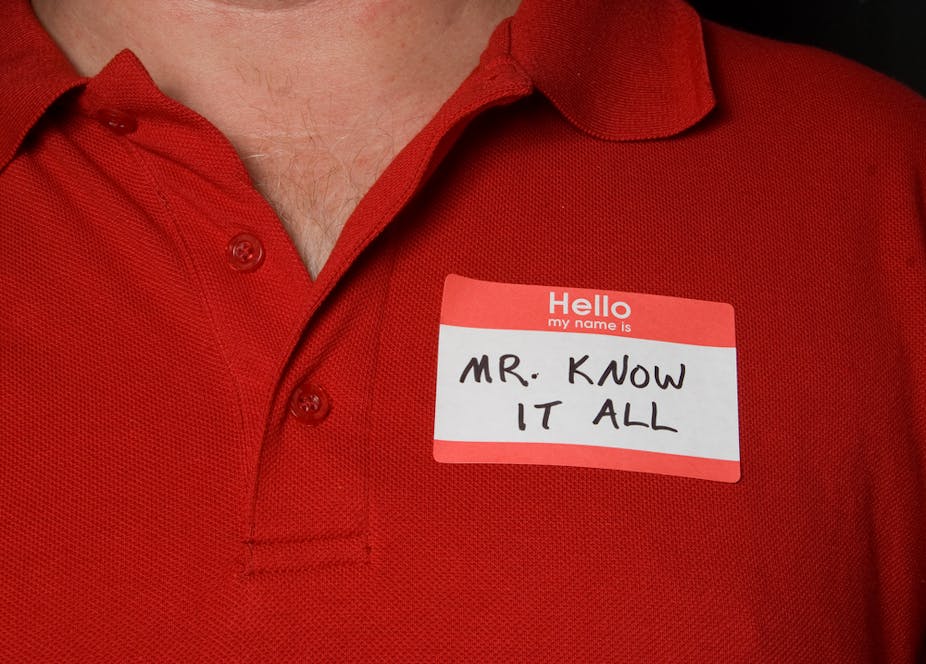

Knowing isn’t the same as doing

So saying that cooperation and communication will improve patient care or safety may provoke a response of: “Well, I could have told you that”, yet we also know how often this type of working falls down. Public inquiries continually repeat recommendations for improved communication, greater transparency and a culture of openness. In the end, then, it’s not quite as obvious as we might have first imagined.

We may think it self-evident that a cooperative, coordinated approach is desirable, not just in hospital discharge, but in every area of modern-day healthcare. We may think it blindingly obvious that colleagues should communicate with each other; but it requires more than a shrug, a knowing sigh or a dismissive retort to discover precisely why cooperation, coordination and communication remain so elusive – and how they might finally be achieved for the benefit of patients and staff alike. After all, knowing something doesn’t work well is quite different from knowing why. Harder still, perhaps, is doing something about it.