In 1866, Adelaide colonist George Hamilton published An Appeal for the Horse, arguing against the harsh treatment of animals. He claimed that in “treating [the horse] as a machine, [people] have forgotten the higher attributes of his nature, and considered only his bone and muscle”.

Hamilton was a trailblazer in challenging the cruel treatment of animals by humans. He loved horses better than many people, and frequently likened them to children, wives, or friends. Although Australian anti-cruelty laws were passed as early as 1837, more specific prohibitions against cruelty to animals were not introduced until the 1860s. Hamilton’s challenge to the boundary we have constructed between humans and animals anticipated considerable recent research that questions this divide.

In contrast, Hamilton’s compassion for Aboriginal people was conspicuously lacking. Empathy is always politicised, and emotional narratives such as Hamilton’s tell us whose lives are worthy of compassion and therefore valuable.

In 1839, on a journey droving 350 head of cattle from Port Philip to Adelaide, Hamilton had a tense confrontation with two Aboriginal men, in which he drew and cocked his pistol, ready to fire. The moment passed, and as he later explained:

Although it was my intention to fire upon my black relations, it was with no desire to kill them. No … they would have been merely winged, shot through the leg or arm, or in some place not vital.

Hamilton contrasted his willingness to harm, if not kill, Aboriginal people with what he saw as the hypocrisy of those “pious persons” who cared more about “ignorant pagan black monsters” than “their white brethren who are, from poverty, neglect and vicious teaching, fast falling into a savagedom far more frightful”. Like many at this time, he pitted the rights of Indigenous people against those of poor whites, whether in Britain or in the colonies.

Picturing colonial violence

As an “overlander” who helped “open up” land routes between Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide during the years from 1836 to 1845, Hamilton was a veteran of frontier conflict. His fine-grained narratives and carefully observed drawings and prints provide a valuable insight into the story of white settlement in South Australia.

In 1845 Hamilton wrote:

The black man who roams over these wilds their lord and master is little elevated by nature from the beasts that inhabit his native forests, so far beneath the rest of his species that he seems to be standing on the line of demarcation between instinct and reason.

It seems that humans have always needed to elevate ourselves in contrast to those who are radically different - the “other” - whether that be animals, non-white races or women. This process was fundamental to imperialism and, more often than not, it was violent.

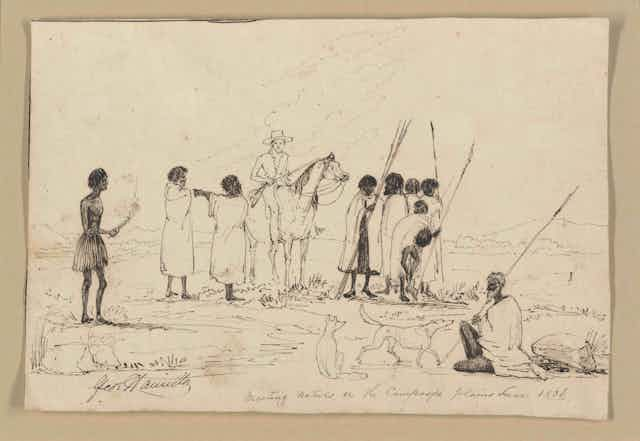

There is a shift in Hamilton’s views from his first forays into the bush around 1836 to his late-19th-century reminiscences. Some of his early drawings, such as “Meeting natives on the Campaspi plains, Victoria, June 1836”, express a friendly curiosity, offering many details of material culture and exchange between white travellers and local Aboriginal people.

But after the Myall Creek Massacre of June 1838 in north-western New South Wales, colonists became more circumspect regarding frontier clashes with Aboriginal people. Following this massacre, seven white men were hanged for the murder of 28 Wererai people, outraging white colonists and increasing racial tensions over subsequent decades. Recent research by Lyndall Ryan documents the sites where thousands of Aboriginal people and tens of settlers were killed in south-east Australia.

During the 1840s, Hamilton began to produce less sympathetic images, including many drawings and prints depicting frontier violence. These sometimes showed conflict in relatively objective terms, such as his ink drawing “Overlanders Attacking the Natives”.

Even “Natives Spearing the Overlanders’ Cattle”, while showing Aboriginal people as aggressors, remains relatively neutral.

But a series of lithographs from the late 1840s have a nastier edge, losing their quality of realist observation and descending into caricature. These show Aboriginal people attacking white colonists, with ironic titles such as “The Harmless Natives”, or “The Persecuting White Men”. Here Hamilton directs our sympathy from black to white.

As Hamilton’s legacy shows us, emotional narratives and images are a powerful way of defining our relations with others.

This process is also fundamental to modern global warfare, as Judith Butler argues in her analysis of war journalism. It can be seen at work wherever interests compete. For Hamilton, Aboriginal people’s defence of kin and country challenged his own right to colonise and posed a personal threat. This made it easy for him to demonise Aboriginal people.

On the violent frontier, Hamilton was typical in defining the white colonist as victim and Indigenous Australian as persecutor, declaring in 1845:

We may soon look forward to the time when murders perpetrated by the savage on the settler will be considered something more than a peccadillo, and we may hope to see the settler at liberty to protect his life and property without the fear of escaping the blacks’ tomahawk only to run his neck in the hangman’s noose.

Here we see the emotional logic of Hamilton’s imperial cultural hierarchy and his political deployment of compassion. Suddenly, the seeming incongruity of Hamilton’s scorn for threatening Aboriginal people alongside his sympathy for the faithful horse makes perfect sense.

Jane Lydon will explore Hamilton’s life and works in a lecture at the University of Adelaide on October 18.