If the films of Norman Jewison, who died on Jan. 22, 2024, had a unifying theme, it was how his characters searched for meaning and questioned the rules of their worlds.

No matter the genre of the scores of films he directed – from “In the Heat of the Night” to “Fiddler on the Roof” – his characters grew by confronting their own biases and preconceptions, even if it meant sacrificing things they once held dear. And as a media scholar, I see the Canadian director’s 1975 film “Rollerball” as one of his most underrated works. In it, the film’s hero, Jonathan E., is a star athlete who’s willing to risk his own life to avoid being a pawn for his corporate overlords.

Set in a dystopian 2018, the film helps make sense of today’s political and cultural struggles, which are taking places as corporations and the wealthy consolidate their control over the information systems, newspapers and media outlets that once served democracy.

Comfort in exchange for subservience

In “Rollerball,” Jewison depicts a future in which corporate feudalism has replaced democratic nations, with entire sectors of the economy consolidated under single corporations. Instead of citizens governing themselves, subjects live in cities ruled by corporations that demand unwavering fealty.

The corporations provide for their vassals, giving them material comforts and entertainment, which work to assuage resentments fueled by rigid social inequality. Jewison’s glassy-eyed characters pop pleasure pills like Tic Tacs to zone out and dream of being executives making decisions, even as they can’t even approach that sort of agency, power and control.

The oligopoly asks only that no one interfere with corporate imperatives.

Unable to find meaning as individuals, people instead seek it out in media spectacles like Rollerball, a kind of motorcycle roller derby meets football meets basketball.

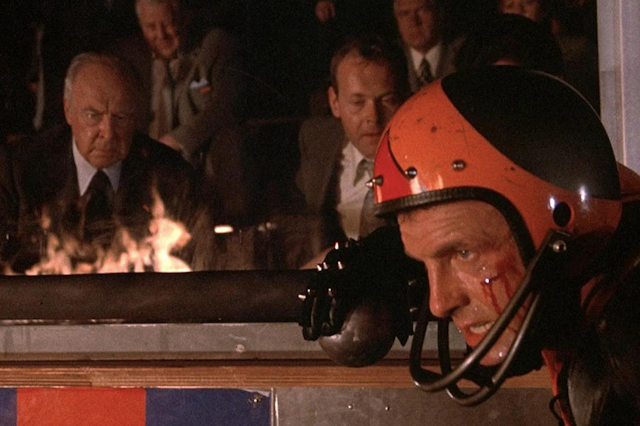

Each major city has a Rollerball team that helps residents channel their aggression and cultivate a sense of belonging. Jonathan E., played by James Caan, competes for Houston, a city owned by the Energy Corporation.

Rollerball serves an enormous social purpose, because it acts as a form of entertainment while also reinforcing the idea that corporate society, as one executive says, “is an inevitability.”

Though it allows for rare individuals to rise out of poverty to fame when chosen by the corporation, all of them are eventually sacrificed to the brutality of the game or to shifting corporate priorities. The audience learns that corporations make all decisions and that strength is power.

According to Bartholomew, the head of the Energy Corporation, “the game is designed to break men,” revealing people to be as disposable and fungible as pistons or rods in a machine.

Jonathan E. is the one player who can’t be broken; he starts to resent the executives telling him what to do, and he wants to know how corporate decisions are made. Who decided to take his wife from him one day and reassign her to serve as the wife of an executive in Rome? Why can’t he choose the path his life will take?

The owners eventually decide that Jonathan E. is getting bigger than the game, and that his popularity as a player is a threat to their control. They want him gone and order him to retire. When Jonathan refuses, the executives change the rules of the game so he’ll be killed.

He survives and keeps investigating. But he can’t find any information.

There are no newspapers serving the public – no libraries or books to consult. The only people allowed to answer questions are “corporate teachers,” who impart information based upon instruction from executives.

Jonathan E. eventually travels to the oligopoly’s database, an artificial intelligence named Zero, or the “world’s brain,” as its chief computer scientist calls it. All human knowledge is stored on it. But because Zero’s interpretations, analyses and outputs must constantly realign with the whims of the executives, there is no shared sense of truth or reality.

Journalistic phlebotomy

I can’t help but think of “Rollerball” as the journalism industry continues to crater. Like most sectors of the economy, the news sector is controlled by a handful of owners, and most of them have prioritized profits over serving the public interest.

If the media layoffs, mergers and acquisitions of January 2024 are any indication, it’s shaping up to be another brutal year for the industry.

Researchers at the Medill School’s Local News Initiative predict that one-third of community newspapers that operated in 2005 will be gone by the end of 2024. In January 2024, the owners of two venerable legacy news reorganizations, The Los Angeles Times and The Baltimore Sun, decided the bottom line was more important than their ability to gather news.

The Baltimore Sun has suffered through the sort of ownership malpractice affecting local papers everywhere – a kind of phlebotomy where corporate owners buy newspapers and, in the name of “saving” them, bleed them dry.

In 2021, the private equity fund Alden Global Capital acquired the Sun and 200 other newspapers across the country from Tribune Publishing. Then, they drained newsrooms of resources, leaving them as shells of their former selves – places that cheaply churned out syndicated content, rather than focus on the issues important to the communities where they were located.

The Sun’s new owner, Sinclair Broadcast Group’s David Smith, made his fortune plundering local broadcast news, draining their local community value and turning them into outlets centered on national politics, rather than local issues, with a right-wing slant that mirrored his own. Smith is signaling he’ll do the same thing with The Baltimore Sun. I won’t be surprised if he ends up morphing what’s left of the paper into another mouthpiece for his pet issues, rather than one that serves Baltimore’s public interest.

The Los Angeles Times has suffered a slow bleed by a succession of owners. It, too, was owned briefly by Tribune Publishing before being acquired by billionaire doctor and pharmaceutical executive Patrick Soon-Shiong in 2018.

On Jan. 23, 2024, Soon-Shiong decided that the LA Times should fire 23% of its reporters and close parts of its multimedia portfolio that served the city’s marginalized residents.

Owners versus the public good

The oligopoly of owners who are consolidating and liquidating media outlets are asking citizens to be satisfied with the information they provide – much like the corporate overlords of “Rollerball.”

People can spend hours entertained by thrilling bowl games, experience outrage and schadenfreude on social media, and get sucked into AI-boosted infotainment at their pleasure. All they have to do is acquiesce to the sovereignty of private corporations and give up their freedom to govern themselves.

A half-century ago, Jewison warned that a corporate-owned world would threaten the democratic world. In “Rollerball,” Jonathan E. remains unsatisfied that all knowledge communicated through the media is determined by hidden executives. With black box algorithms choosing what content appears on news feeds and social media feeds, it’s eerily similar to the predicament society faces today.

“Why argue about decisions you are not powerful enough to make yourself,” the executives point out to Jonathan E. “Just enjoy your ‘privilege card.’”

And yet when asked to choose between “comfort and freedom,” Jonathan chooses freedom.

Resisting corporate domination of media won’t be easy, either. But it’s necessary in order to prevent U.S. democracy from slipping into plutocracy.