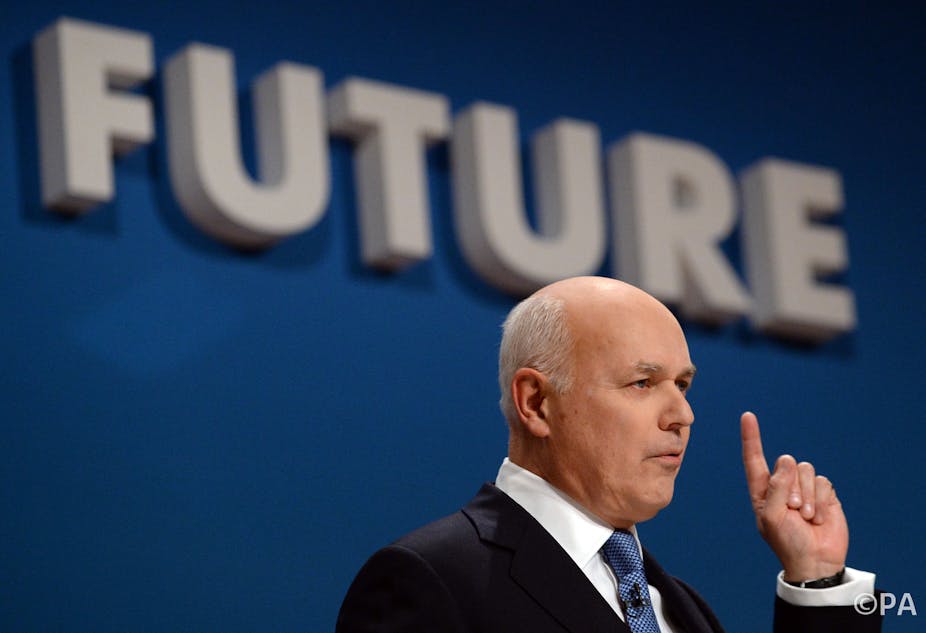

Iain Duncan-Smith has made his feelings about benefits claimants clear: poor families are to be given pre-paid cards, loaded with payments, to make sure they spend the money on food, rather than their “self-destructive habits”.

Earlier, the Tory conference heard from Chancellor George Osborne, who announced further changes to benefits. He revealed that he will introduce a limit to the amount of money households can receive each year and cap jobseekers’ allowance.

Both announcements attracted applause from the audience but these are schemes based on a philosophy about the poor that assumes that those who depend on the state will fritter money away given half the chance. That is not a view backed up by evidence.

Research has shown that, in other countries, it is better to transfer money and resources directly to the households in poverty and allow them to decide how best to spend it. And there is no reason that the same shouldn’t be true in the UK.

It’s a deceptively simple idea, but a powerful one that goes against the UK government’s rhetoric on benefits. Put simply, benefits claimants do not spend all their money on booze and fags if they are left to their own devices.

Social assistance programmes do work. They aren’t about throwing money out of helicopters; recipients can be selected and monitored along the way to make sure the money is being used in the best way. They don’t have to be restricted in how they spend the money.

In a recent paper, World Bank economist David Evans looked at all the evidence on whether poor households really did fritter away their cash on temptation goods. By analysing various studies they found that they did not, despite common assumptions to the contrary.

The view from abroad

There has been an astonishing growth of social assistance programmes in developing countries in recent years, programmes that have been successful in tackling extreme poverty and protecting the poorest from income shocks. These programmes currently reach around three quarters of a billion people in the South, and are making a large contribution to the decline in extreme poverty and inequality worldwide.

Countries with much higher rates of poverty than the UK have had great success at trusting families to spend their benefits wisely. Programmes such as Mexico’s Oportunidades, Brazil’s Bolsa Familia, South Africa’s Child Support Grant, and India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme are all examples of the approach in action.

All provide regular cash transfers to households in poverty and aim to improve their nutrition, help make sure children go to school, and encourage expectant mothers to have regular check-ups. Without such transfers, the costs of transport, school uniforms, medicine and looking for a job could well be prohibitive.

Central to the success of the Brazilian scheme is the use of conditions. Recipients are required to attend school or go to the doctor as part of the deal. The same applies in the UK but benefits are taken away as punishment if the claimant doesn’t meet their side of the bargain. In Brazil, it is assumed that the family is in need of additional support if they don’t meet the requirements and the state works with them to decide what that support should be.

These programmes have high set-up costs whether they are running in a developing or developed country, but if they are well designed and have political support, they can work extremely well. Duncan Smith’s welfare reforms, on the other hand, are over-running and over budget – that is the burden to the tax payer.

The acceleration of universal credit, as he has now announced, coupled with the introduction of pre-paid benefit cards, is only going to add to infrastructure needs of the UK’s benefit system.

Rather than obsess over whether a minority of British welfare recipients are spending their money on booze and fags, the British media and public would do better to consider whether their taxpayer contributions are supporting a robust, sustainable programme that can be delivered practically.

Duncan-Smith is right – we need to “reach out to the margins of society that have been left behind for too long”. But there needs to be a serious focus on the steps of support that can actually help people out of poverty.

That means access to education, literacy, minimum wage, child care, and support around disabilities, illness and the multitude of complex needs that exist when you are at the margins of society.

This is what is provided by the more holistic social assistance schemes used in other countries. It will have a more far-reaching effect on lifting people out of poverty than a pre-paid card that denies them a fag.