Senator John Sidney McCain III, who has died of brain cancer aged 81, was in many ways in a class of his own. A storied war veteran and 36-year fixture in the US Congress, he forged a career unlike any other in recent American political history.

McCain was born on August 29 1936 at Coco Solo US Naval Air Station Panama to Admiral John McCain Jr and Roberta McCain. McCain’s grandfather, John Senior, had also been a four-star admiral. Graduating from the US Naval Academy in 1958, McCain became a naval aviator, and in 1967 he volunteered for combat duty in Vietnam. On July 29 that year, McCain narrowly escaped death when a rocket accidentally launched from another aircraft exploded in his aircraft while he was in the cockpit. McCain was able to jump clear, but the accident ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed the USS Forrestal and killed 134 of her crew.

On his 23rd combat mission over North Vietnam, McCain’s plane was shot down with a surface-to-air missile. He survived the crash, but was plunged into an ordeal as a prisoner of war that would last for five and a half years.

After returning from Vietnam, McCain remained in the Navy until 1981, after which he embarked on a second career in politics. He was elected to the House of Representatives as a congressman from Arizona in 1982, then to the Senate in 1986. In 2000, he made an unsuccessful bid for the Republican presidential nomination against George W. Bush of Texas, but a second effort in 2008 secured him his party’s nomination.

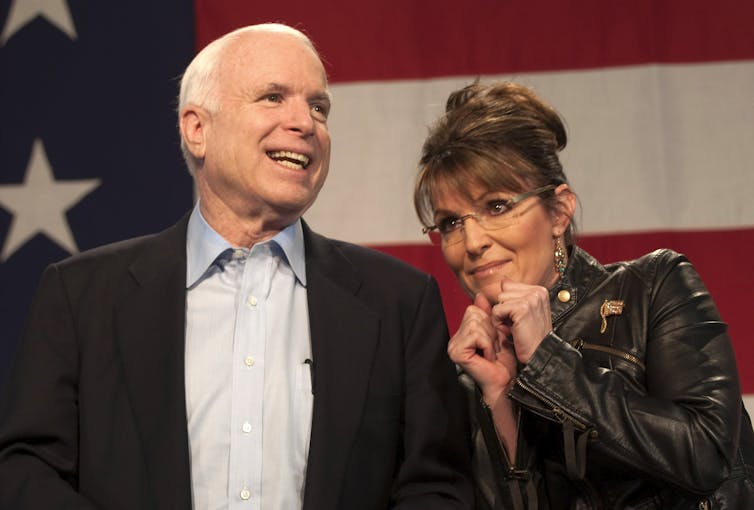

During that campaign, eager to gain the support of the right wing of the Republican Party, McCain lurched further to the right than his own convictions might otherwise have permitted. His most momentous decision was to choose as his running mate the largely unknown governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin.

Only recently, McCain suggested that he actually considered the extraordinary step of instead choosing Senator Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, a former Democrat, as his running mate, but was persuaded by his political advisers to select Palin instead. Whatever really happened, the decision reinforced McCain’s reputation as a self-styled political “maverick” – but while beloved of the conservative grassroots, Palin proved to be an inept and ignorant liability. And in the end, she and McCain were roundly defeated by Barack Obama.

Hawk and dove

McCain was undoubtedly a conservative. He was a supporter of Reaganomics, and he and his first wife were close friends of the Reagans for a time. In 1983, McCain voted against the establishment of a Martin Luther King national holiday; he opposed gun control and also abortion.

He consistently promoted a hawkish foreign policy, supporting the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2007 counter-insurgency “surge” that saw an additional 20,000 American troops dispatched to the country. More recently he supported US intervention in Syria, and favoured an aggressive policy towards Iran and North Korea.

But from the outset of his political career, McCain was also prepared to oppose the norms of modern Republicanism on points of personal conviction. He spent years declaring his belief in global warming, pressing for political campaign finance reform, and was not afraid to make common cause with Democrats as an advocate for offering undocumented immigrants a path to citizenship.

Most recently, McCain established himself as the “acceptable face of Republicanism” as opposed to the current occupant of the White House. After the 2016 election, McCain many times butted heads with the Trump administration, in particular supporting the investigation of alleged Russian interference in the electoral process.

According to McCain, his diagnosis of brain cancer in July 2017 left him free to “vote my conscience without worry”, famously flying back to Washington against the advice of his doctors to vote against the effective repeal of the Affordable Care Act (aka “Obamacare”) on July 25, spelling the end of a Republican promise. In the last weeks of his life, McCain opposed the confirmation of Gina Haspel as the new director of the CIA, saying “her refusal to acknowledge torture’s immorality is disqualifying”.

McCain always had his critics. Some attacked his temperament; others, including the current president, questioned the reality behind the cultivated maverick-warrior image he presented in his three memoirs – the last of which, The Restless Wave, was published only this year. But if McCain’s memoirs are indeed rather shallow works of self-promotion, that’s just an example of the politician’s stock-in-trade.

Yes, McCain undeniably milked his experience as a prisoner of war for all its worth. But that too is hardly unusual for a US politician with a service background – and the price McCain paid during his years in the “Hanoi Hilton” was far higher than anything asked of most of his posturing colleagues.

McCain’s political legacy will always be somewhat tarnished by his crass decision to elevate Palin, whose rise inadvertently encouraged the same bitter and intolerant anti-intellectual conservatism that defines the era of Donald Trump. But that was only one chapter in a career spanning more than three and a half decades. Right up until his death, McCain worked to promote a more inclusive, principled conservatism. One day, that might be recognised as his true legacy.