Last year the Australian governments (federal and state) spent AU$6.23 billion on the budget line “climate change and environment”. This probably seems a reasonable amount to most taxpayers, compared to that spent on arts and sport (AU$3.33 billion) or aged care services (AU$12.95 billion). The AU$6B makes up about 1% of combined federal and state budgets; it is dwarfed by welfare (30%), health (16%) and education (9%).

Of course, the problems faced by the environment are huge. We humans are decidedly winning our battle with the other species which share this country. In the Australian list of threatened species there are 445 fauna species; 55 are already extinct, 45 critically endangered, 141 endangered and 198 vulnerable. For plants, there are 41 species extinct among the list of 1,240 variously threatened.

Throwing more money at the problem will not fix the damage done by human civilisation. We can only do that by acknowledging the way our pursuit of economic growth drives other species’ decline.

Look at the 20 key threatening processes under federal law: the rapacious rabbit, the cunning fox, the poisonous cane toad, the wallowing feral pig and the browsing goat. True we admit a faint stamp of human ingenuity by listing land clearing (most of the best lands well cleared by now anyway), fishing by-catch and introduced grasses in northern rangelands. Nowhere does legislation highlight Homo sapiens and its economic tentacles as the primary driver of the decline in our fellow species.

Defending this institutional myopia is an art form in itself. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act - the main federal act protecting the environment - allows for applications for new threatening processes. An application in 2010 by the Australian Conservation Foundation to list population growth as a threatening process appears to have failed the policy test. The Yellow Crazy Ant threat on Christmas Island sailed through. The ACF application reviewed the population growth spurts underway in the coastal wetlands of South East Queensland, the Mornington/Western Port biosphere in Victoria, the Fleurieu Peninsula in South Australia and the Swan Coastal Plain in Western Australia. While the drivers for population growth and land settlement outcome varied for each of these case studies, in no region was a positive prognosis for threatened communities and species assured.

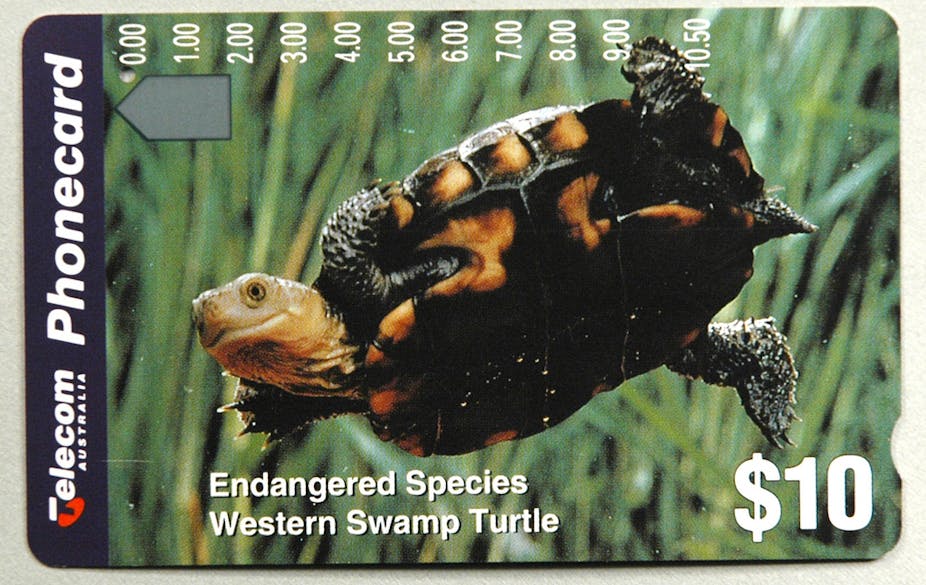

While money for conservation matters, Homo sapiens conducts its species war on many fronts. Take just one fauna species critically endangered by population growth and related impacts, the Western Swamp Tortoise. The tortoise lives on a narrow strip of the Swan River floodplain in Western Australia. A preferred diet morsel for the wily fox, the tortoise is a diffident breeder whose habitat has been overwhelmed by a cascade of land use change since the mid 1800s and now survives surrounded by humans.

The tortoise recovery team’s aim is “to have four or five secure, viable populations, rather than the one that currently exists. Threat abatement activities include habitat improvement, water supplementation, predator control, captive breeding, public education and fire management”. More Federal and State budget dollars will see this recovery plan endure. But multiply this effort by the 395 fauna species alive on the list and you’ll understand why ecologist’s eyes tend to glaze over during The Treasurer’s well crafted budget delivery.

Altering Australia’s population trajectory by reducing immigration rates (Immigration and Customs budget $4.04 billion) to give other species a chance probably won’t make the shortlist of budget highlights. After all, population growth provides a vital boost to economic growth due to great multipliers of value adding from building and renting houses. Changing our obligations in international trade (Foreign Affairs and Trade budget $6.77 billion) might be another consideration. Sydney University’s trade and biodiversity study released last year showed our export activities affected 158 endangered species while our imports had an impact on 135 species abroad, mostly in developing countries.

The World Trade Organisation’s Article 20 of the World Trade Organisation’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade has the legal framework to apply border tariffs or import constraints on production chains that damage the environment. However, only a really foolhardy treasurer would wage a trade war on behalf of threatened animal species when his revenue base seems to be dropping like a stone. Where is Ken Henry when hairy nosed wombats and many other species need him?

So the battle between humans and the rest of Australia’s species is unlikely to alter its pace and intensity based on the most recent budget numbers and the self-interest evident in Australian consumers and voters. Perhaps keeping current recovery programs viable is a modest hope. Any bigger initiatives require the budget headspace provided by increasing GST to 15 or 20% along with obvious savings highlighted by the recent Grattan Institute report.

Doing real things about species protection and recovery requires substantial changes to population growth rates, settlement patterns, personal consumption and the composition of international trade, both inwards and outwards. I’ll not be expecting much for other species, apart from a bit of tinsel and fairy floss, on this budget night.