One Nation thought it could smell sweet electoral success for much of the Western Australian state election campaign.

The party had reason to be confident about its prospects, despite the recent debacle concerning Rod Culleton, the former One Nation and later independent senator found ineligible to stand for parliament.

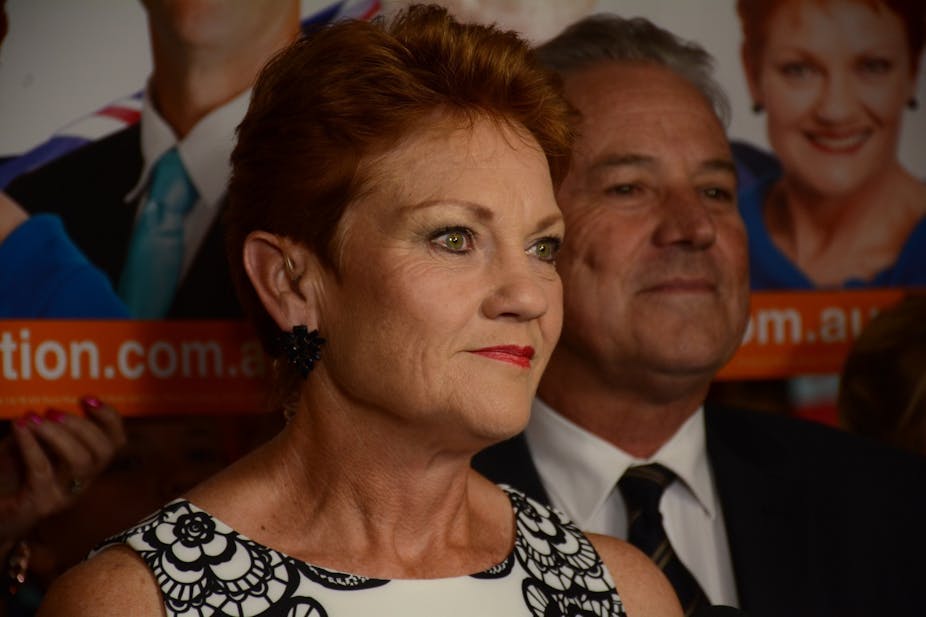

The party’s founder, Pauline Hanson, had resumed the leadership mantle and had emerged as a high-profile deal-maker in the Senate. Hanson used her profile to support her “down-to-earth, upfront and honest grassroots” candidates by making frequent visits to the state during the campaign.

Polls had the party as resurgent and on track to win up to 13% of the primary vote.

On the strength of its strong performance in the polls, both major parties were reported to have been jostling for One Nation’s preferences. It was the Liberals that sealed the deal in the end. Liberal leader Colin Barnett was unapologetic, even if “uncomfortable”, about the decision.

This deal was significant for One Nation.

The preference pact had the potential to enhance the electoral prospects of One Nation candidates contesting upper house regions.

The deal was also important because it signalled that One Nation was no longer a political pariah. Former Liberal prime minister John Howard defended the preference deal with One Nation on the grounds that “everyone changes in 16 years”. And high-profile Liberal senator Arthur Sinodinos argued One Nation are “a lot more sophisticated”.

But the party’s supposed new-found sophistication was rarely on show during the campaign.

Hanson applauded Russian President Vladimir Putin for his patriotism and strong-man persona, but paradoxically likened a policy that made eligibility for certain forms of family payments and childcare benefits contingent on parents vaccinating their children as akin to living in a dictatorship.

“Bloody lefties” within the education system were denounced as the cause of social problems that were afflicting regional towns. Muslims were accused of having “no respect” for Australia, and making preparations to eventually overthrow Australian governments.

The party struggled to contain its candidates. Two were disendorsed and two more resigned during the campaign. Four days before polling day, two former high-ranking party officials who were sacked from the party went public with their decision to take legal action against Hanson for age discrimination.

And three days before the election, there were concerns the party’s how-to-vote cards were not legally compliant.

In a final blow to an already chaotic campaign, Hanson declared the preference deal it had struck with the Liberals had likely done the party “damage”.

What cost the preference deal?

Certainly the result reveals that One Nation failed to perform as strongly as the early opinion polls had predicted. With 67.25% of the lower house vote counted, One Nation attracted only 4.74% of primary votes.

What then does this all mean? Was the preference deal a mistake for One Nation? Can a so-called anti-establishment party enter into a preference deal with an establishment party and survive to tell the story? The prevailing opinion is “no”.

However, let’s consider the claims that have been levelled about the preference deal. The main claim is the preference deal was the primary cause of One Nation’s electoral woes.

There is definitely polling data which shows many voters were opposed to the deal. What is less clear is if this opposition translated into action at the ballot box. If, for example, we calculate (or average) One Nation’s primary vote according to the actual number of lower house seats it contested, then its primary vote is around 8.26%.

While this figure is well short of the early double-digit polling results tipped for One Nation, it suggests that its support did hold up (and this is in spite of an electoral campaign that was chaotic and ill-disciplined).

The second general claim is the idea that a preference deal for either party under any circumstances is tantamount to electoral suicide.

Again, this argument might be something of a stretch. What appeared to actually blight this agreement was the particular electoral and political dynamics that surrounded it, and not the mere fact of a deal being negotiated between the two parties.

The Liberals struck a preference deal that favoured One Nation over its historical alliance partner, the Nationals. While the Liberals might have been justified by its decision, it ultimately proved very difficult to square with the conservative base more generally. The preference deal made a desperate party appear even more desperate.

One Nation agreed to a preference deal with the Liberals even though it proposed the partial privatisation of the electricity utility, a policy One Nation rejected. The planned privatisation of the utility was deeply unpopular, opposed by as many as 61% of voters.

In spite of its protestations to the contrary, One Nation had hitched its wagon to one of the most controversial policy issues of the entire campaign.

It could be argued that under different conditions, this preference deal need not have generated as much collateral damage as this one seems to have caused.

Any damage arising from this preference deal to One Nation is likely to prove fleeting. The party is on track to win two seats in the Legislative Council, most likely with the assistance of Liberal preferences.

In the end, the real danger for One Nation lies not with who it chooses to enter into preference deals with, but how it manages it internal affairs, and the conduct of its elected members – especially its leader.