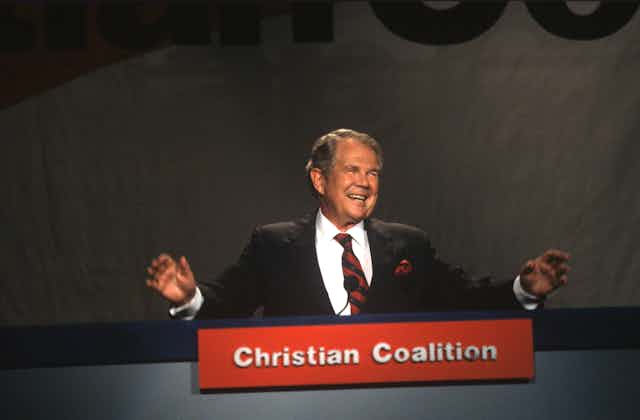

Televangelist Pat Robertson, who died at the age of 93 on June 8, 2023, was a familiar face on television for many conservative Christians, attracting a million viewers each day on his flagship show, “The 700 Club.”

In 1960, Robertson founded the Christian Broadcasting Network and in 2018 launched the first 24-hour Christian television news channel. He also founded an evangelical school in Virginia Beach in 1977, the Christian Broadcasting Network University, and changed its name to Regent University in 1990.

Over the past several years, scholars writing for The Conversation have commented on Robertson’s enormous influence on American politics. In 1988, he sought the Republican nomination for president; though his bid was unsuccessful, he continued to play an important role politically through his popular show.

Here are three articles from our archives that explain his influence in blending religion into U.S. politics.

1. Religious right and influence on public policy

Roberston was part of the Moral Majority, founded by Jerry Falwell in 1979. That group was a broad coalition of conservatives – mostly white evangelical Christians, who came to represent the “Religious Right,” wrote Richard Flory, a scholar at USC Dornsife.

Those leaders, including names such as James Dobson, Tim LaHaye, Pat Robertson and Phyllis Shlafly, came to have an enormous impact on American politics, which extended to an influence on public policy.

The group supported what Flory said is now “a familiar agenda”: legislation for “traditional” family values, prayer in schools, opposition to LGBT rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, abortion and other issues.

Indeed, as host of “The 700 Club,” Robertson made comments that were often seen to be controversial and racially insensitive. For example, he once compared gay people to thieves and murderers.

Read more: Revisiting the legacy of Jerry Falwell Sr. in Trump's America

2. Conflating Christian and American identities

At the time of the Jan. 6, 2021, attack at the U.S. Capitol, scholar Samuel Perry wrote about the many Christian symbols on display that day that were signs of Christian nationalism’s influence on the event.

He noted the role of evangelical Christian media in promoting that type of Christian nationalism, which suggests that Christians risk being suppressed unless they are in control of the state.

Christian radio stations that bring mostly white evangelical messaging have seen a growth over the past few years. But the genre’s roots go back to Robertson’s Christian Broadcast Network, which has operated for decades and, according to Perry, “similarly blends politics with religion.”

While Robertson condemned the attack at the Capitol, he had previously claimed that President Donald Trump’s reelection was certain.

According to Perry, Roberton’s blend of politics and religion may not necessarily contribute to Christian nationalism, but “it does contribute to conflating Christian identity with American identity.”

Read more: The Capitol siege recalls past acts of Christian nationalist violence

3. Long history of Christian media

There is no doubt the Christian Broadcasting Network has been highly influential, particularly among evangelicals. Trump used the network from time to time to reach this support base.

According to Jason Bruner at Arizona State University, Christians have “shared and shaped the content of world news and information through a distinctly Christian viewpoint” since at least the 19th century.

He described how Christian missionary publications served as informal foreign correspondents for a broadly Christian public in the eastern United States and Western Europe. Those missionaries highlighted the genocide against Assyrian and Armenian Christians in the eastern Ottoman Empire. They also helped build international opinion against the brutal reign of King Leopold of Belgium in the decades straddling the turn of the 20th century, during which some 10 million people are estimated to have died.

Read more: How Christian missionary media shaped the world

As Bruner wrote, Robertson put the network in a longer line of “creating a global Christian identity through knowledge production” and left an enormous impact on both religion and politics in the U.S.