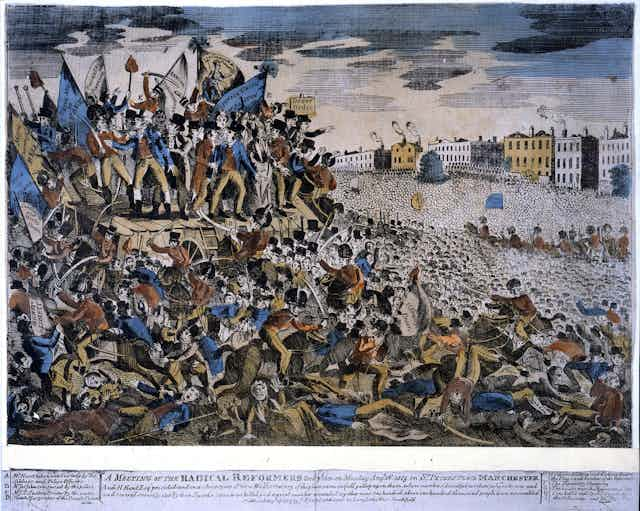

At St Peter’s Field in Manchester, England on Monday August 16 1819, an estimated 18 men, women and a child were massacred by British cavalry and up to 500 were wounded. “Peterloo” has come to play an important role in working-class, radical and reformist history in Britain – as well as in the history of democracy.

In contrast to Peterloo, there has been little commemoration of the 1919 Amritsar Massacre in Britain – which saw up to 600 men, women and children murdered by the British Indian Army – and another 1,500 to 1,800 wounded.

That Amritsar’s centenary has not received a similar level of attention as Peterloo is unfortunate as to better appreciate British history and understand the country today, it is important to look at the sociopolitical and economic systems that allowed such harms to happen. In this instance, systems that were responsible for producing both Peterloo and the Amritsar Massacre 100 years apart.

The importance of Peterloo

The estimated 60,000 people who gathered in Manchester on that day 200 years ago did so to demand parliamentary reform, including the enfranchisement of working-class men – which was regarded as extremely threatening by British elites.

The massacre itself has been described as “one of the most significant events in modern British history”. And historian Robert Poole has also referred to Peterloo as Britain’s “Tiananmen Square”.

Read more: Peterloo massacre: how women’s bravery helped change British politics forever

As such, the massacre has largely been viewed as a unique event in Britain’s story. But this perspective forms part of a “little island” approach to British history – and ignores what happened in the quarter of the planet that Britain colonised.

For much like Peterloo, the 15,000-20,000 crowd that gathered in Jallianwalla Bagh – an area of land enclosed by high walls – in Amritsar were there to listen to speeches on April 13 1919. These were speeches against the Rowlatt Act – the colonial regime’s attempt to maintain the extraordinary powers it had assumed in India during the First World War.

Most were unaware of General Reginald Dyer’s proclamation earlier that day prohibiting political gatherings. And upon hearing news of the gathering, the general raced over and ordered his troops to fire on the peaceful crowd gathered there – which they continued to do for the next ten minutes.

Hundreds of men, women and children were murdered – and many more were badly wounded. Dyer’s aim was to produce a “sufficient moral effect” to quell dissent against British rule in India. The brutal act followed events in the preceding century ranging from the Indian Revolt of 1857 to the Kuka outbreak of 1872 – both of which saw violence perpetrated by the British in India.

Despite the horrific bloodletting of the Amritsar Massacre, the wide range of commentary and debate about it at the time and the fact that – like Peterloo – 2019 marks an important anniversary there has been little remembrance of it in Britain. A notable exception is the exhibition “Jallianwala Bagh 1919: Punjab under Siege”, at the Manchester Museum.

When the Amritsar Massacre does attract attention, the primary focus is on whether or not Britain should apologise for it. But such an apology would only serve to exonerate empire by reducing imperial violence to an act committed by one man. The Amritsar Massacre was not, as such demands for an apology suggest, either an exceptional nor aberrant aspect of British colonial rule –- as critics at the time were well aware.

A new understanding

There are many reasons, of course, that the UK commemorates and remembers Peterloo less so events such as the Amritsar Massacre. One is the need to purge problematic aspects of a national history. Peterloo has been incorporated into the national history as an example of the country’s rocky but ultimately triumphal march to democracy, but no such claim can be made for the Amritsar Massacre. Yet incorporating events such as the Amritsar Massacre, as well as the wider history of empire, into British history is vital for understanding modern Britain. The UK must begin constructing a national history that includes the reality of its imperial past.