Like many inventions, the discovery of Teflon happened by accident. In 1938, chemists from Dupont (now Chemours) were studying refrigerant gases when, much to their surprise, one concoction solidified. Upon investigation, they found it was not only the slipperiest substance they’d ever seen – it was also noncorrosive and extremely stable and had a high melting point.

In 1954 the revolutionary “nonstick” Teflon pan was introduced. Since then, an entire class of human-made chemicals has evolved: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS. There are upward of 6,000 of these chemicals. Many are used for stain-, grease- and waterproofing. PFAS are found in clothing, plastic, food packaging, electronics, personal care products, firefighting foams, medical devices and numerous other products.

But over time, evidence has slowly built that some commonly used PFAS are toxic and may cause cancer. It took 50 years to understand that the happy accident of Teflon’s discovery was, in fact, a train wreck.

As a public health analyst, I have studied the harm caused by these chemicals. I am one of hundreds of scientists who are calling for a comprehensive, effective plan to manage the entire class of PFAS to protect public health while safer alternatives are developed.

Typically, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency assesses chemicals for potential harm, it examines one substance at a time. That approach isn’t working for PFAS, given the sheer number of them and the fact that manufacturers commonly replace toxic substances with “regrettable substitutes” – similar, lesser-known chemicals that also threaten human health and the environment.

Toxic chemicals

A class-action lawsuit brought this issue to national attention in 2005. Workers at a Parkersburg, West Virginia, DuPont plant joined with local residents to sue the company for releasing millions of pounds of one of these chemicals, known as PFOA, into the air and the Ohio River. Lawyers discovered that the company had known as far back as 1961 that PFOA could harm the liver.

The suit was ultimately settled in 2017 for US$670 million, after an eight-year study of tens of thousands of people who had been exposed. Based on multiple scientific studies, this review concluded that there was a probable link between exposure to PFOA and six categories of diseases: diagnosed high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular cancer, kidney cancer and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of peer-reviewed scientific papers have shown that many PFAS are not only toxic – they also don’t fully break down in the environment and have accumulated in the bodies of people and animals around the world. Some studies have detected PFAS in 99% of people tested. Others have found PFAS in wildlife, including polar bears, dolphins and seals.

Widespread and persistent

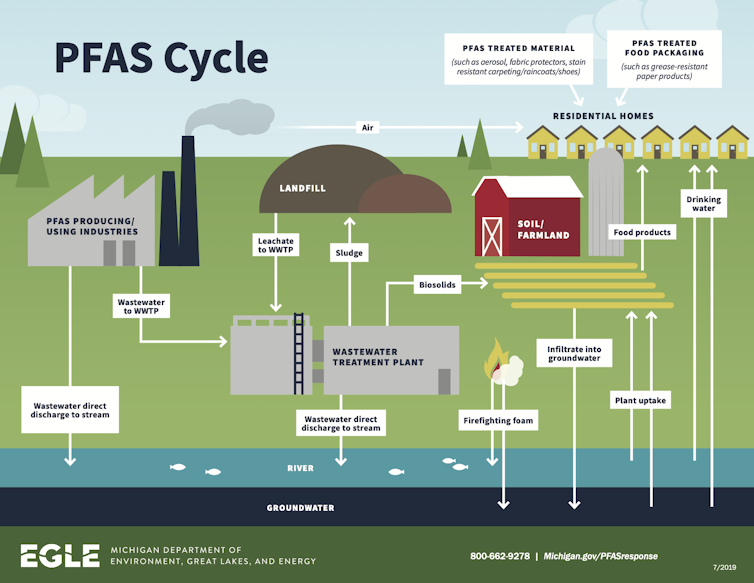

PFAS are often called “forever chemicals” because they don’t fully degrade. They move easily through air and water, can quickly travel long distances and accumulate in sediment, soil and plants. They have also been found in dust and food, including eggs, meat, milk, fish, fruits and vegetables.

In the bodies of humans and animals, PFAS concentrate in various organs, tissues and cells. The U.S. National Toxicology Program and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have confirmed a long list of health risks, including immunotoxicity, testicular and kidney cancer, liver damage, decreased fertility and thyroid disease.

Children are even more vulnerable than adults because they can ingest more PFAS relative to their body weight from food and water and through the air. Children also put their hands in their mouths more often, and their metabolic and immune systems are less developed. Studies show that these chemicals harm children by causing kidney dysfunction, delayed puberty, asthma and altered immune function.

Researchers have also documented that PFAS exposure reduces the effectiveness of vaccines, which is particularly concerning amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regulation is lagging

PFAS have become so ubiquitous in the environment that health experts say it is probably impossible to completely prevent exposure. These substances are released throughout their life cycles, from chemical production to product use and disposal. Up to 80% of environmental pollution from common PFAS, such as PFOA, comes from production of fluoropolymers that use toxic PFAS as processing aids to make products like Teflon.

In 2009 the EPA established a health advisory level for PFOA in drinking water of 400 parts per trillion. Health advisories are not binding regulations – they are technical guidelines for state, local and tribal governments, which are primarily responsible for regulating public water systems.

In 2016 the agency dramatically lowered this recommendation to 70 parts per trillion. Some states have set far more protective levels – as low as 8 parts per trillion.

According to a recent estimate by the Environmental Working Group, a public health advocacy organization, up to 110 million Americans could be drinking PFAS-contaminated water. Even with the most advanced treatment processes, it is extremely difficult and costly to remove these chemicals from drinking water. And it’s impossible to clean up lakes, river systems or oceans. Nonetheless, PFAS are largely unregulated by the federal government, although they are gaining increased attention from Congress.

Reducing PFAS risks at the source

Given that PFAS pollution is so ubiquitous and hard to remove, many health experts assert that the only way to address it is by reducing PFAS production and use as much as possible.

Educational campaigns and consumer pressure are making a difference. Many forward-thinking companies, including grocers, clothing manufacturers and furniture stores, have removed PFAS from products they use and sell.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

State governments have also stepped in. California recently banned PFAS in firefighting foams. Maine and Washington have banned PFAS in food packaging. Other states are considering similar measures.

I am part of a group of scientists from universities, nonprofit organizations and government agencies in the U.S. and Europe that has argued for managing the entire class of PFAS chemicals as a group, instead of one by one. We also support an “essential uses” approach that would restrict their production and use only to products that are critical for health and proper functioning of society, such as medical devices and safety equipment. And we have recommended developing safer non-PFAS alternatives.

As the EPA acknowledges, there is an urgent need for innovative solutions to PFAS pollution. Guided by good science, I believe we can effectively manage PFAS to reduce further harm, while researchers find ways to clean up what has already been released.