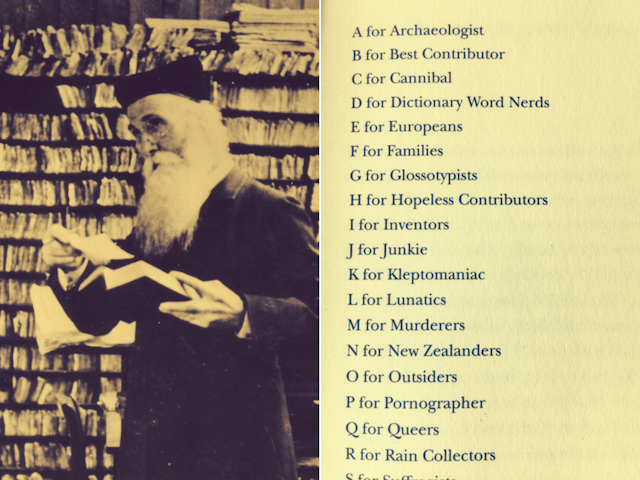

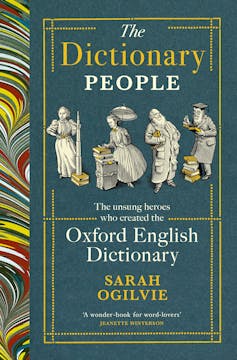

The Dictionary People: The Unsung Heroes who Created the Oxford English Dictionary is a celebration of words and word-people: authors, editors, publishers, linguists, lexicographers, philologists, obsessives, pedants. Its author, Sarah Ogilvie, was formerly an Oxford English Dictionary editor and wrote the 2013 book Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Review: The Dictionary People: The Unsung Heroes who Created the Oxford English Dictionary (Chatto & Windus)

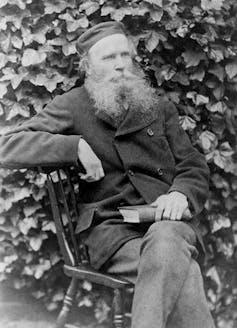

Ogilvie’s focus in The Dictionary People is on editor James Augustus Henry Murray (1837-1915), who orchestrated a collective, pre-digital mode of crowd-sourcing to produce the first edition of the dictionary.

An unlikely lexical prodigy, Murray had left school at 14. He had worked on a dairy farm, then as a teacher and a bank clerk. In between those and other jobs, he developed a broad knowledge of foreign languages – including Tongan and classical Greek – and became a serious student of etymology and philology. On that basis he was enlisted to help with the dictionary.

For his work, Murray built a large iron shed in his garden that was called, grandly, “the Scriptorium”. On cold days, which were many, Murray’s editorial assistants would wrap their legs in newspaper to stay warm.

Lacking a university education, Murray was alert to status and perceptions. He gifted himself the names “Augustus” and “Henry” to impart gravity and distinction to his otherwise humble-sounding name. After he was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1874, he wore his scholar’s cap every day.

Murray’s OED was to be much more than a list of words and their definitions. It would also be a philological document, providing examples of how words had appeared in books and newspapers. That goal was well beyond the capacity of an editor and a small team of shivering assistants. Hence the crowd-sourcing. A vast network of people would join the project, sending in paper slips showing examples of English words in context.

There were so many contributors sending so many slips that the Royal Mail installed a red pillar box outside Murray’s home. Many of the contributors (nearly 500) were women, and some of those were among the OED’s super-contributors, sending in thousands of slips over many years.

When it was finally published in 1928 after Murray’s death, his edition of the OED contained 414,825 entries, with 1.8 million illustrative quotations.

Allusions and anecdotes

The catalyst for The Dictionary People was Ogilvie’s rediscovery of Murray’s ribbon-tied address books in a “dusty box” in the basement archive of Oxford University Press.

The address books revealed an extraordinary collection of contributors, including Virginia Woolf’s father Leslie Stephen, Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor, the American army surgeon William Chester Minor, and Sir John Richardson, surgeon and naturalist on John Franklin’s first voyage in search of the Northwest Passage.

Like Murray’s OED, The Dictionary People is a collective exercise. In addition to other supporters and sources, Ogilvie has assembled the book with the assistance of ten student researchers at Stanford University, with an eye for fascinating allusions and anecdotes.

We learn from The Dictionary People that Jane Austen was the first to write the word “outsider” and that a cousin of Eleanor Marx hallucinated that she had written Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women.

We also learn that the OED entry for ruffle – “to rumple, to destroy the smoothness or evenness of something” – took an illustrative quotation from Eleanor’s 1886 translation of Madame Bovary, and that, at the age of 27, a not-yet-famous J.R.R. Tolkien worked on the OED as an editorial assistant with the lexicographer Charles Onions, whose family referred to Tolkien as “Jirt”, short for J.R.R.T.

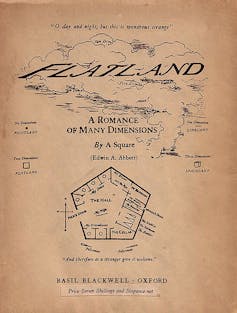

Yet another delightful detail: 18 words from the science-fiction novella Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (1884), including “dimensionable” and “nondimensionable”, made it in to the dictionary. Written by mathematician and theologian Edwin Abbott Abbott under the pseudonym “A. Square”, Flatland is the story of a square who visits Pointland, Lineland and Spaceland “to explore the possibility of other dimensions”.

A book with Austen, Woolf, Tolkien and sci-fi? The Dictionary People is irresistible.

Gonzoesque

The Dictionary People is a good example of a newish genre of gonzoesque bibliographic history. Other examples include Denis Duncan’s equally excellent Index: A History of the (2022), Emma Smith’s Portable Magic (2022) and my book The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders (2017).

This genre aims to tackle potentially dry, bookish topics in an engaging way. It analyses serious subjects diligently but informally, blending high and low culture, respectable and disreputable content.

Compared to Duncan, Ogilvie is more relaxed with the informality and the edgy terrain. The Dictionary People lacks rock’n’roll, but there is plenty of sex and drugs. Ogilvie devotes a chapter to the erotomaniac Henry Spencer Ashbee, whom Duncan left out of his book, despite the lurid splendour of the index to Ashbee’s anonymously published erotic memoir My Secret Life (1888).

Some parts of The Dictionary People are possibly too gonzoesque, even for me – such as when William Minor takes a paper-knife and a tourniquet and cuts off his own penis.

In the midst of this symphony of words and colour, there are inevitably some wrong notes. To bring Murray’s list of contributors to life, Ogilvie has assembled a series of biographical portraits. These provide the book with its structure and narrative drama, but some of the biographical entries are stronger than others.

Towards the start of The Dictionary People, Ogilvie confesses to being “thrilled” that the list of OED contributors includes “not one but three murderers, a pornography collector [and] a cocaine addict found dead in a railway station lavatory”.

The addict is Eustace Frederick Bright, the focus of Chapter J. Unfortunately, it is one of the weaker chapters in The Dictionary People. Parts of it read like a Tinder profile, or perhaps the formulaic obituary of the died-young Oxbridge scholar. “Bright by name and bright by nature”, Eustace was

a top student […] passing all his examinations with flying colours […] A good-looking young man, he had an engaging and outgoing personality, and many friends.

There are some unhelpful speculations, such as “if heroin had existed in Bright’s day […] he probably would have tried it”. We learn that Bright died after drinking a phial of liquid cocaine, then taking several tablets, along with morphine. “He began to vomit, then collapsed and, lying on the toilet floor, he died.”

Ogilvie speculates about Murray’s reaction to Bright’s death:

Murray, as a teetotaller, would have been shocked and saddened by the demise of one of his most promising students and volunteers. News of Bright’s overdose came at a difficult time for him. Life in the Scriptorium was particularly stressful […] because of the successful publication [in America] of the Century Dictionary and the generously funded progress of […] Funk and Wagnall’s Standard Dictionary of the English Language.

The chapter towards the end on Chris Collier, however, is one of the strongest: a highlight of the book. Collier was a naturist from Brisbane who, like Murray, left school at 14. He began contributing to the OED in the 1970s, sending 100,000 slips over a period of 35 years.

For his contributions, Collier pulled numerous quotes from the Courier Mail. He sent bundles of slips “eccentrically wrapped in old Corn Flakes packets with pieces of cereal and dog hair stuck to them”. As a result, Brisbane’s main newspaper is proportionally over-represented in the OED.

Ogilvie describes meeting Collier in a Brisbane park in 2006, when Collier was around 70 years old. Dressed Don Dunstan-style in a t-shirt and “very short shorts”, he was reading – of course – the Courier Mail.

Ogilvie refers regularly to “word nerds”. She is a natural connoisseur, who delights in words such as fritillaria (a type of flowering plant), eweleaze (an upland pasture for feeding sheep), absquatulate (to leave abruptly), apheliotropic and apogeotropic (botanical terms for plants that, respectively, turn away from the sun and bend away from the earth), agamogenetic (asexual reproduction), zoopraxiscope and zoogyroscope (two early forms of movie projector), aophiolaters (people who worship snakes), and cephaleonomancy (“divination by placing a donkey’s head on coals, and watching the jaws move at the name of a guilty person”).

But Ogilvie (or her editor) is not a textbook word nerd. She suggests, for example, that the New Zealand katipo and the Australian redback are the same species of spider; though related, they are not. And do we really need to be told that “non-conformably” means “in a manner that is not conformable”?

Writing about Eustace Bright, Ogilvie remarks that the word junkie “seems the closest adjective beginning with j to describe Murray’s former student”. Rather than “adjective” here, a more punctilious word nerd would have said “word” or “noun”.

Read more: Giving back to English: how Nigerian words made it into the Oxford English Dictionary

The bigger picture

The overarching claim of The Dictionary People is that it shines a light on the “unacknowledged” and “unsung heroes” of the OED. The claim is made in the subtitle and repeated throughout the book. Ogilvie states that she has “uncovered lives that have not necessarily been written about in the history books”.

I’m not sure what Ogilvie means by “necessarily” here, but the claim of unsungness is doubtful. Other works have covered similar ground. Quite a few of the people profiled in the book have been written about extensively. Simon Winchester’s bestselling The Surgeon of Crowthorne (1998), for example, focused on William Chester Minor and was turned into a (not very successful) Hollywood film with Mel Gibson and Sean Penn.

Many books have been written on the search for the Northwest Passage and John Franklin. There are numerous biographies of Leslie Stephen, J.R.R. Tolkien and the Marxes. OED contributor Edward Sugden was profiled in a book by his daughter, as well as in the Australian Dictionary of Biography and the centenary history of Melbourne University Publishing. Henry Spencer Ashbee is the subject of Ian Gibson’s book The Erotomaniac (2001). Ogilvie’s previous book covers some of the same ground as The Dictionary People (it contains the Jirt anecdote, for example) and she wrote about Chris Collier for the Australian Book Review in June 2012.

I think Ogilvie would agree that the “unsung” claim is in many instances an unnecessary overstatement. Her main contribution with The Dictionary People is to put all the biographical portraits together to reveal a new and bigger picture.

What does this bigger picture reveal? In a compelling way, Ogilvie’s mosaic of contributors disrupts the assumptions we make when we see a copy of the OED. She tends to write from a British perspective, but she highlights that other countries and cultures have strong stakes in the OED. She describes how the dictionary was an English project and a British project, but also an empire project and a global project.

The OED was not solely an English enterprise in another sense, too. In the field of dictionary production, as Ogilvie shows, continental Europeans had the jump on England, producing dictionaries with similar methods and ambitions. Murray and other OED editors took a lot from European (and American) precedents and competitors.

What else can we see anew by grouping the contributors together? Murray’s OED was ostensibly a conservative academic project, but it was also a radical and democratic one. It contains countless neologisms. It drew input from people of all genders and classes. Many of the contributors lived far outside the academy, on the margins and fringes of Victorian and Edwardian society. A significant proportion were probably neurodiverse, and a large number were politically, socially and sexually diverse.

This is a cliché of course, but the OED took strength from this diversity. The power and richness of the dictionary depended on reaching into distant places and fields, including literature, commerce, medicine and science. The OED transcended disciplines and it transcended, literally, the walls of institutions such as prisons and asylums. William Minor, the fourth most prolific contributor to the dictionary, worked from the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Ogilvie’s bigger picture reveals that the English language is not owned by a club or a committee or a university or by people from a particular social class or place. It is a global language in its sources, its reach and its ownership. The language, and the literary and scholarly traditions that were built with it, belong to all of us.