The past few months have seen the flotation of Royal Mail, the Lloyds share sale and the first national employee ownership day. The theme linking these three developments is one that has been around since the 1980s: the belief that everyone should own property and shares in companies.

With David Cameron directly linking the Royal Mail sale to this “popular capitalism”, an idea that he says “allows everyone to share in the success of the market”, it is startling to see how little has moved on over the past few decades. In particular, if the current landscape is so familiar, then surely the lessons from the past should help us navigate around today.

Back in the 80s, many economists pushed the view that there was a certain logic in persuading employees to buy shares in their own companies, rather than getting the average family to directly hold a small portfolio of shares. According to this view, the latter policy was doomed to failure in the long run.

Giving employees of newly privatised companies a large number of cheap shares had some logic. In particular, the Thatcher government saw it as a way of weakening union power and hence easing in needed changes in employment practices.

Even if employees knew the objective was to weaken their rights in the longer term, it still made sense for them to take up the deals. If no one else buys then you get a freebie on the shares and no loss of worker power. But if everyone buys, it makes no sense to give up your own bribe since the union power will be diluted anyway. Though not entirely down to the share ownership strategy, labour relations in privatised industries indeed changed dramatically after sell-offs.

More, generally however, persuading workers to take up shares in their companies proved far harder. There are obvious dangers for employees because if the firm does badly not only is your job at risk but with employee ownership your wealth is going to take a hit at exactly the same time.

Someone, therefore, had to put money on the table to provide some protection against this bundling of risk, and the taxpayer duly contributed a little. But, despite the political enthusiasm, companies never responded in a big way and the model of employee ownership never really matched the hype.

Popular capitalism

In the 80s the government’s policies encouraging small-scale investors to buy up shares in privatised companies came to be known as “popular capitalism”.

As a result of fears that the BT flotation in 1984 might not be a success, sweeteners were provided to the general public. People duly signed up in droves and rather liked to be given money to buy and then sell on shares. Spotting the political benefits of having a large number of share owning voters, the justification for the sweeteners in subsequent privatisations rested on popular capitalism as an end in itself, not a means of getting the job done.

There are, in any case, solid economic arguments against a policy that gives ordinary people incentives to become long-term holders of small, undiversified portfolios of shares. It leads to far greater concentration of risk and higher transactions costs than those faced by larger investors.

Hence, these small investors have to be “bribed” to hold a small portfolio without any obvious significant long run benefit to society (unlike employee share ownership which may bring some benefits to companies and the economy).

Nothing’s changed

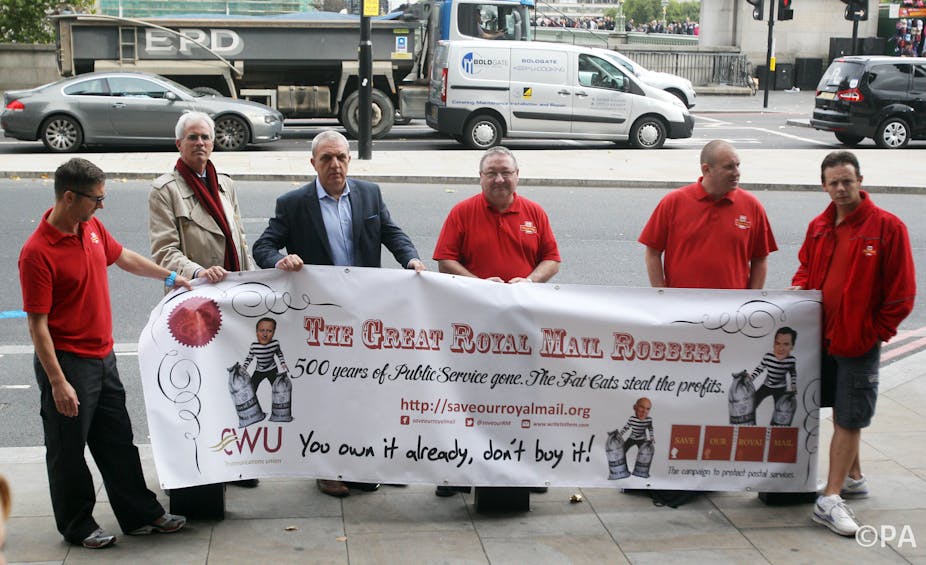

Jump to 2013 and very little seems to have changed. The Royal Mail flotation gave about 10% of the share allocation to employees, against a backdrop of worker strikes. Whether the share allocation impacts on employee attitudes in the coming months is not certain but it would be surprising if it did not go some way towards splintering workers and hence aiding management to make changes.

Even more reminiscent of the early privatisations is the massive oversubscription of Royal Mail shares offered to private investors. Even before launch newspapers were predicting “instant profits”, and published articles on the best way to move the shares on cheaply. For this flotation, the government even set in place special procedures to make this cheaper and more straightforward.

While this may make a few people happy, history suggests long term gains from this policy will be minimal or non-existent. Popular capitalism may have delivered a quick political win for Margaret Thatcher, but it brought no discernible impact on long run share ownership.

The 1990 privatisation of regional electricity companies makes the point clearly. By this point, the popular capitalism model of privatisation was well honed. There were millions of applications from private investors and the shares were so heavily oversubscribed that many missed out.

Small private investors made a quick buck and exited quickly, with 40% of the original shareholdings sold within ten months. Indeed, almost all of the electricity distribution networks are now absent from the stock market, with a current list of owners that includes Warren Buffet, JP Morgan, and Spanish utilities giant Iberdrola.

A popular capitalist sale?

Next up is Lloyds Banking Group, with hints that a portion of the government’s stake may be sold to retail investors.

But nothing in the Royal Mail flotation to date suggests that large, attractive, retail offerings of the government’s banking stakes will end up with results any different from the 80s and 90s wider share ownership policy. Though the scale of interest in Royal Mail shares has been somewhat surprising, the main message should not be to contemplate another round of popular capitalism.

The push for increased employee ownership over the last year or so is also all very reminiscent of the enthusiasm 25 years ago. But very little came of that and it is hard to see what has changed this time round.

So what do we learn from all this déjà vu? Royal Mail is something of a one-off throwback and should be viewed in this way. The unexpected mass oversubscription from private investors and using employee share ownership in the face of union pressure all sounds familiar, but it certainly gives us no blueprint for the way to deal with the banks.