A leaked UN memo to the Security Council has warned that a peacekeeping force in the African nation of Burundi would be unable to stop large-scale violence should it erupt in an ongoing crisis caused by president Nkurunziza’s election for a third term.

However it is not too late for Nkurunziza to choose his legacy: either be remembered as a war criminal facing prison or death, or renowned for solving a dangerous political situation. A new round of peace talks is due to take place this month but Burundi’s government recently announced there had been “no consensus” on a date.

Nkurunziza has the opportunity to engage fully in peace talks with the help of the African Union and the United Nations. By doing so, he will be able to show the Burundian people that he can lead his state to peace, and concentrate on what he can do best: providing further education for all, and in the long term, economic development, too.

A questionable third mandate

Since April 2015, when Nkurunziza decided to run for another term, over 400 people have been killed and hundreds of thousands have been internally displaced or have sought refuge in neighbouring countries.

The president’s third mandate was considered illegal by some Burundians, the international community, and some experts because under the country’s constitution and the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement of 2000, only two terms are allowed.

However, the Burundian Constitutional Court countered that the renewal of the presidential term for another five years was not against the constitution of Burundi, because Nkurunziza was appointed by the parliament, and not elected by the people, for his first term – a decision that a leading opposition member claimed had been made under pressure by the Nkurunziza regime.

Lengthening terms

But the stance of the international community seems hypocritical: presidents Paul Kagame in Rwanda and Sassou Nguesso in Congo-Brazzaville have also sought changes to the constitutions of their states to run for a third mandate, but there is more criticism of Nkurunziza for effectively doing the same. Even though the overall environment was “not conducive” to an inclusive, free and credible electoral process on election day, the UN said, “Burundians in most places went peacefully to the polls to cast their ballots”. The head of the electoral commission, Pierre Claver Ndayicariye, told reporters that Nkurunziza won 70% of the votes cast. This needs to be acknowledged by the international community.

Violence was fomented by both the government and the demonstrators. The government has led a campaign of political repression that has included beatings, arrests and house-to-house searches, with nearly 3,500 detained. Demonstrators have also been violent, and have attacked military sites [in the capital Bujumbura](http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc12117.doc.htm](http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc12117.doc.htm). Today, the president can either encourage violence further, and face being handed over to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague or he can lead Burundi out of violence, and engage with mediating the conflict.

Nkurunziza is certain to face the ICC if he does not stop Burundi from descending into further violence, because Burundi has ratified the ICC statute. The prosecutor of the ICC, Fatou Bensouda, has already warned that she would act if wide-scale abuses are committed.

Nkurunziza will be in the same situation as other heads of states who have been wanted by the ICC: Omar al Bashir in Sudan in 2009 (though investigations into alleged war crimes in Darfur were halted in 2014); Laurent Gbagbo in Ivory Coast (whose trial at the ICC begins this month); and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya in 2011. A violent end is another possibility, and was the fate of Laurent Kabila in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2001, and Gaddafi in 2011.

At a crossroads

That said, president Nkurunziza could nonetheless become the leader who prevents another civil war. From 1993 to 2006, an estimated 300,000 people were killed in Burundi due to political conflict with ethnic manifestations, and there are fears that this may happen again if the matter is not resolved in talks.

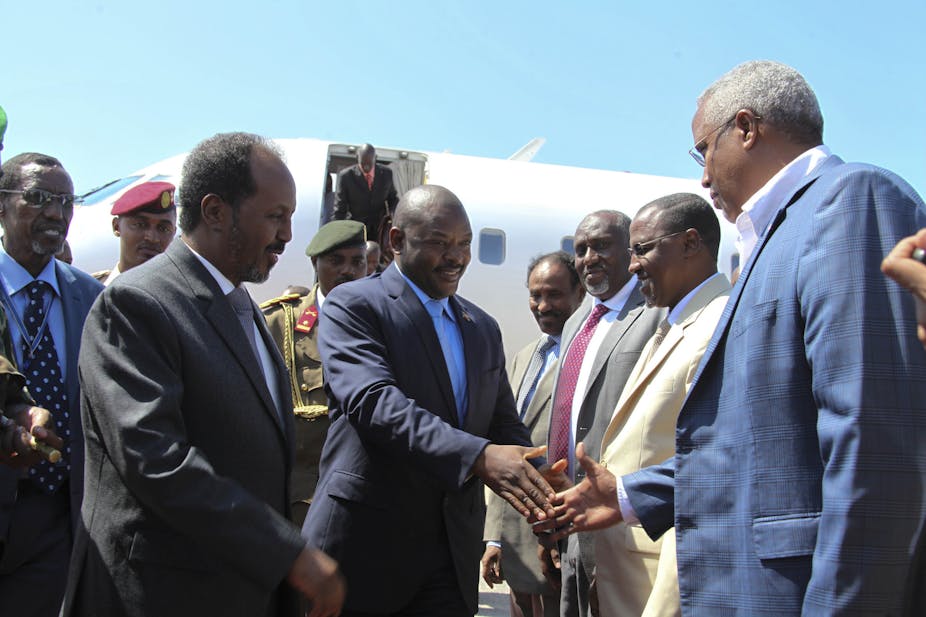

For the moment, as academic Devon Curtis says, the crisis in Burundi is political and not ethnic. To avoid further bloodshed, it must remain so, and president Nkurunziza could lead the way out of the current crisis by engaging with the African Union which is [prepared to help stop violence](http://theglobalobservatory.org/2015/12/burundi-african-union-maprobu-arusha-accords/](http://theglobalobservatory.org/2015/12/burundi-african-union-maprobu-arusha-accords/), and with the United Nations which is currently at loss as to how to deal with further violence, but which can help with mediation.

To alleviate the tense situation, Nkurunziza needs to make the most of the window of opportunity of negotiation he still has with the international community. Likewise regional actors who show bias need to stay clear from the mediation process. Rwanda in particular has been backing demonstrators in Burundi.

Nkurunziza is at a crossroads. The path he takes will be a crucial one for the country – and himself.