By 2020, 1.2 billion people or 16% of the world’s population will be entering their childbearing years, with 90% of these in the developing world. Along with education, the availability of effective contraception is a major key to overcoming the poverty trap.

Meanwhile, the rate of new HIV infections in women and girls is rapidly increasing to match rates seen in men, making them the missing link in the success of many HIV/AIDS prevention programs.

A paper published this week in Science Translational Medicine offers new hope. It outlines an early but significant step forward in the development of a dual contraceptive method offering protection from the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in conjunction with contraceptive action. More on that in a moment.

Recent advances in female contraceptives

Since the introduction of the pill in the 1960s, most new approaches to reversible contraception for women have focused on manipulation of the female hormones, estrogen and progesterone. These include rods that are implanted below the skin (Implanon®) and the intrauterine system or IUS (Mirena), which slowly release progestins.

These progestin-only contraceptives have high efficacy, are fully reversible and provide protection against pregnancy for up to five years. But discontinuation rates are as high as 30%, mainly due to irregular bleeding patterns, which most women deem unacceptable. New forms of IUS that are easier to insert are under development.

Another popular device is the vaginal ring (NuvaRing), a bendable plastic ring which is inserted into the vagina. It offers monthly combined hormonal contraception, with three weeks of ring use and one ring-free week each month. The vaginal ring acts like the contraceptive pill but does not require daily action, thus facilitating compliance.

So why do we need new contraceptives?

The currently available contraceptives come with some major shortfalls.

Firstly, the use of many contraceptives including the oral contraceptive pill is associated with relatively high user-failure rates. Nearly 40% of the 85 million unintended pregnancies each year world-wide are due to failure of contraception.

Secondly, many couples discontinue using their chosen contraception after initiation because of method-related reasons, such as side effects, health concerns or inconvenience.

Finally, contraceptive use varies throughout the world. Usage continues to be very low in places such as Africa, due to limited access to services, logistic failures resulting in unavailability of products, and cultural, religious or personal reasons.

Current research and development

As progesterone is essential for establishment and maintenance of pregnancy, most current research and development is based on compounds known as anti-progestins. These work by inhibiting the synthesis or action of this vital hormone.

Administering these compounds through different means may help improve uptake and continuation of use. But many women don’t easily tolerate the manipulation of their hormones, or do not wish to use such contraceptives.

New contraceptive methods for women could include non-hormonal methods that will provide short-term protection when required and dual-acting methods that protect against both sexually-transmitted diseases and pregnancy.

Research is continuing world-wide to identify target molecules for the reproductive processes leading to pregnancy: egg production, fertilisation and implantation into the womb. A number of these have already been identified. But challenges remain, particularly around the development of small molecule inhibitors to block these targets at their sites of action: the ovary, the fallopian tubes and the uterine cavity.

A team of colleagues at Prince Henry’s Institute, headed by Associate Professor Guiying Nie, have identified one such molecule that may provide both contraceptive action – by blocking implantation – and protection against HIV infection. But while they now have an inhibitor of this molecule, they haven’t found the right vaginal delivery mechanism.

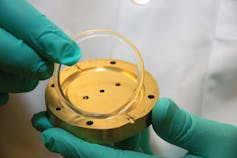

This is where the study in this week’s Science Translational Medicine offers a new opportunity. Rachel Singer and her colleagues at the Population Council in New York have shown that new vaginal rings impregnated with an inhibitor of HIV transmission protected macaques from infection. In other words, the ring successfully delivered the inhibitor to the monkeys’ vaginal fluids and tissues.

This is a significant finding because previous efforts to deliver HIV-preventing microbicides in vaginal gels have proven ineffectual.

While the new study with vaginal rings has limitations, largely due to the high cost of studying macaques (one of few appropriate animal models for human contraception), it does provide important proof of concept.

So, how would it work?

A vaginal ring would be inserted monthly (as for NuvaRing), prior to or immediately following intercourse. The compound released would act within the vagina to prevent HIV. It would also reach the woman’s uterine cavity and give the womb a non-receptive surface, preventing embryo implantation.

Additional inhibitors could also be included to protect against sexually transmitted diseases.

It’s important to note that the research is still in its early stages – and timeline to get any new drug to market is long, due to the rigorous testing required to meet regulatory requirements. So it could be ten years or more before a duel contraceptive becomes available.

Renewed hope for better contraception

Pharmaceutical companies have traditionally been unwilling to support contraceptive development, preferring to focus on commercially successful drugs such as those for cancer or heart disease. Indeed, the need to provide contraceptives at very low cost to developing countries is a severe limitation for companies.

The advances in contraceptive research and development, along with the renewed international focus to help women in the developing world access effective contraception, provide some hope for a future where women around the world have control of thier family planning and sexual health.