Zones of ocean known as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are all the rage. They have no single or agreed definition, but essentially they are areas of sea in which human activity is restricted or prohibited in order to preserve and protect marine habitat and species. They may be small coastal areas or very large offshore expanses of ocean. MPAs are established by local or national governments in order to address actual or potential threats to the marine environment, to create “blue corridors” and to safeguard the breeding and feeding grounds of various marine species.

The thrust for large-scale MPAs is driven by global targets tied to international obligations under the Convention on Biodiversity 1992. Currently the global target is to protect 10% of the world’s oceans by 2020. But in September, at a side event to the United National General Assembly, the UK environment minister, Michael Gove, proposed that the global target be increased to 30% by 2030. This is not a new idea but it is a big ask, given the current conservative estimate that only around 3% of the world’s oceans are protected.

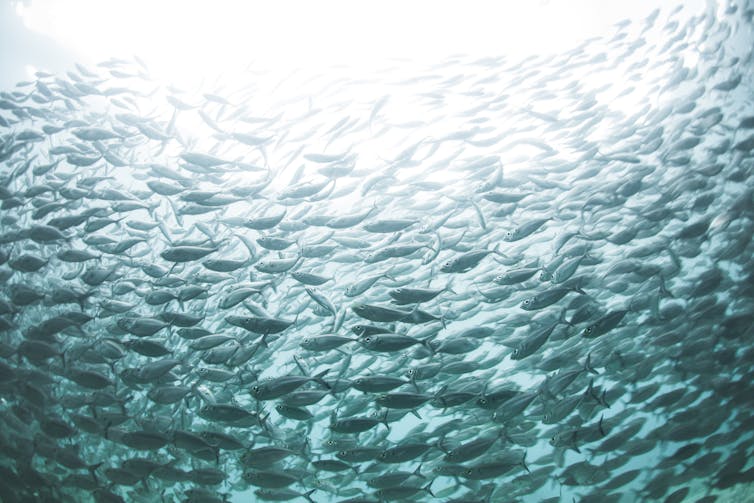

The strongest advocates and lobbyists for large-scale MPAs are conservation charities, research institutes and individuals who catch the attention of the media, such as WWF, National Geographic’s Pristine Seas Initiative, Pew Trusts, and the DiCaprio Foundation. Arguments are made that the most effective MPAs cover large areas (including reefs and the breeding and feeding grounds of open-ocean species such as sardines or tuna), in which all extractive marine activity by humans, such as fishing or mining, is prohibited, and which are maintained as no-take areas for an extended period of time.

The case for creating such protected areas seems like an obvious win in environmental terms. But the science supporting such arguments is inconclusive and mixed, not least owing to lack of sufficient data, especially studies that take a longer-term view. Very large MPAs are also difficult to patrol, despite promises of using satellite and drone technology. Some appear to be little more than “paper parks”, protected in name only with overfishing and so on still happening.

The global commons

The oceans are regarded as part of the “global commons” and the heritage of mankind. And indeed they should be treated as such. But in the “blue” credentials race between nations seeking to declare ever bigger MPAs, there are a number of real political problems.

Large-scale MPAs tend to be declared in areas where there is least likely to be major opposition, especially from fishers. Overseas dependencies and territories are particularly popular. It is much easier to declare large no-take marine protected areas around remote island overseas territories with small, economically dependent, politically weak, communities than coastal areas where articulate, well-resourced commercial interests voice opposition.

The UK, for example, has declared large MPAs around the British Indian Ocean Territory and Pitcairn and it is proposing to do so around Ascension Island, South Georgia, St Helena and Tristan da Cunha. It has pledged to safeguard over 4m square kilometres of ocean around the territories by 2021.

While there may well be noble environmental reasons for doing this, there can also be significant political effects. A 2010 Wikileaks cable suggested that one motivation behind the MPA around the Chagos islands was to prevent resettlement of locals to their homeland. The locals sued the UK government – and although the UK’s Supreme Court has since rejected that this was a motivation, resettlement clearly remains an issue and was referred to by the International Court of Justice in the request for an opinion by the United Nations General Assembly.

The UK is not alone. France, has declared a large MPA around New Caledonia; the US around Hawaii; and Chile around Rapa Nui Rahui (Easter Island). The largest protected areas are all in such distant waters. The legal procedure for declaring an MPA, meanwhile, often skips full democratic debate. In some cases they can be achieved by presidential fiat or executive order.

Lack of representation

All this means that those whose livelihoods are likely to be impacted by restrictions or prohibitions on human activity in an MPA may have little or no involvement in the decision-making process. Meanwhile, there is often no guarantee that promises made about the benefits of the MPA to local inhabitants – such as employment in eco-tourism, better fish size, large catches in the longer term, or profitable visits by teams of researchers and scientists – are delivered.

Linked to this is the fact that the management of MPAs is not always representative. Local or indigenous people have been known to be marginalised. Management is sometimes dominated by the organisations that lobbied for the creation of the MPA is the first place. For example, where resources are limited, NGOs or researchers funded by these NGOs are often relied on.

MPAs are also sometimes used as a trade-off by small states surrounded by large seas to reduce their financial burdens and attract inward investment as well as international approbation. An example is in the Seychelles, where a US$22m national debt owed to overseas lenders was traded to a US-based NGO (The Nature Conservancy) in return for an undertaking that future repayments by Seychelles will be paid into a trust fund directed at the conservation of two extensive MPAs.

Taking steps to address concerns about our shared marine resources is of course commendable. But “ocean grabbing” through the declaration of MPAs is a worry, especially if nations agree the higher target to be achieved in a fixed time. Already there are calls by those urging caution for advocates and lobbyists to adopt ethical guidelines and suggestions for better and more equitable models of management. In some cases these are being heeded. Nevertheless, the targeting of small island states and the role of charitable organisations in what are, ultimately, political decisions, needs to be questioned.

This article was edited on October 23 to clarify certain points.