In his latest state of the nation address Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta called for opening a new chapter of national unity and reconciliation.

This was Kenyatta’s first state of the nation address after last year’s disputed national elections which went into a re-run. Kenyatta reemerged victorious. But it was a pyrrhic victory as his main challenger Raila Odinga had boycotted the rerun.

With both men at the head of their ethnically aligned coalitions, Jubilee and National Super Alliance, the 2017 electoral season was highly charged and polarising. Odinga refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of Kenyatta’s victory and threatened disruption. One of his actions was being sworn in as the people’s president. The mock swearing-in ceremony escalated tensions, culminating in threats of arrests, arraignment and deportation of opposition leaders. The press and civil society were also targeted.

Kenya’s politics has broadly been dominated by two families, the Kenyattas from the Kikuyu and the Odingas from the Luo ethic groups. Uhuru, son of the founding president Jomo Kenyatta, has gone head to head with Raila for the presidential vote twice – in 2013 and 2017. Both elections were marked by ethnic coalition building in which Kenyatta led the most demographically dominant coalition, Jubilee.

On both occasions, the outcome was a kind of ethnic census because Kenyan politics is highly charged along ethnic lines.

Since last year’s tensions, there’s been a visible rapprochement between the two men. Does this signal a broader bottom-up reconciliation process?

Perhaps the reality is that the momentum has started from the top but will take time to get to the bottom. Kenyan politics is notoriously tribal, in part because the system is built for zero sum gains in that it creates winners and losers. As long as this remains the case, Kenya will always remain susceptible to ethnic entrepreneurs as politicians seek to play the ethnic tramp card.

The rapprochement

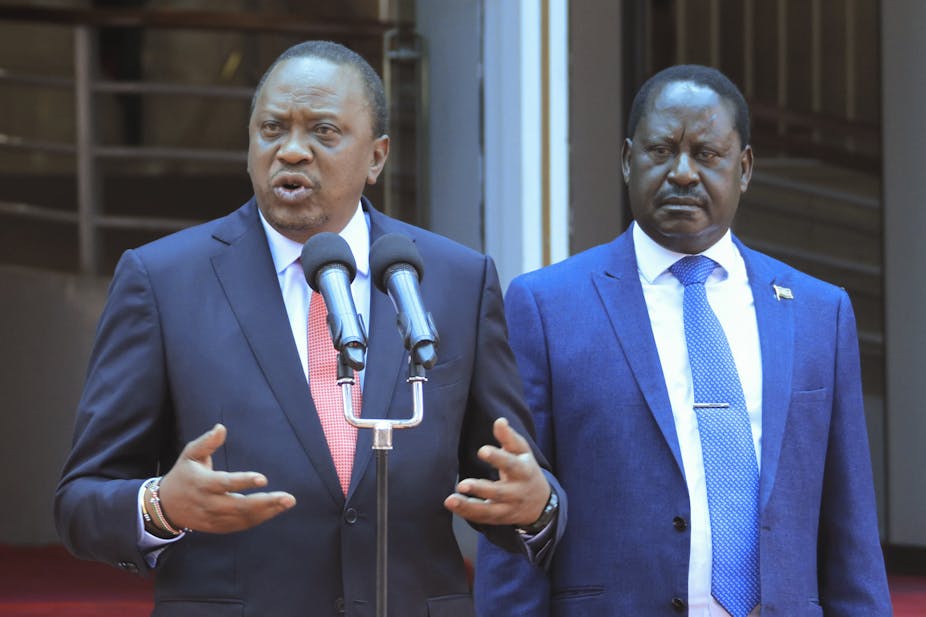

The first sign of rapprochement between the two men took the country by some surprise. A staged handshake in March 2018 signalled a dramatic change of tone and de-escalation of tensions.

Government immediately mellowed its tone towards the opposition, signalling a willingness to engage in constructive dialogue. Within days, Odinga was serving as official government emissary to South Africa to attend Winnie Mandela’s funeral. And a joint team to oversee dialogue was announced.

But what does all this rapprochement mean? The joint statement following the first meeting sought to strike a new political tone. On the surface, it signalled the willingness of both men to draw a line under the acrimony that had emerged from the electoral crisis.

This perhaps points to Kenya’s politics as not only complex but also unpredictable. The country has been here before – after the 2008 elections of Mwai Kibaki thousands died in inter communal post electoral violence. Undertakings were given and efforts were made to build national unity. Yet a decade later, Kenyans are witness to more of the same, albeit on a lesser scale.

Questions are therefore being asked if there is any depth to the Kenyatta-Raila “handshake” beyond portraying both leaders as magnanimous and willing to compromise for the national interests. Their joint statement sought to heal divisions and open a new chapter of inclusiveness and security for all.

For now it is too early to deduce tangible evidence of political inclusivity though tensions have been greatly dialled down. Kenyatta’s public apology to those he “offended” was meant to portray him as a conciliatory statesman.

On the other hand Odinga had more political capital to gain by seeking compromise as a way out of the impasse. His defiance campaign was always deemed more disruptive and a political nuisance than strategically meaningful as the Supreme Court had validated the elections.

Much more is needed

What Kenya needs is transformative change, including constitutional reforms. This should include strengthening structures in which everyone feels represented. And the country needs to design a formula to provide a competitive but an embracing political framework that can deliver enduring peace and prosperity for all Kenyans.

Many lives were lost in the post electoral violence. The two leaders bear special responsibility and should therefore lead efforts to help heal and bridge communal divisions. The recent warming of relations between the two protagonists point to this effort.

But they are not the only players. Others that would be equally important in bringing their communities on board in the broader effort of reconciliation. they include:

William Ruto, current deputy president and an ethnic Kalenjin,

Kalonzo Musyoka, former vice president, wider democratic movement leader, co-principle of NASA and an ethnic kamba, and

Musalia Mudavadi a co-principal of NASA, former vice president and deputy prime minister, leader of Amani National congress and an ethnic Luhya would The role of civil society and religious leaders is also indispensable as partners in reconciliation and rebuilding inter-communal and institutional trust.

In the short and medium term, it’s overly optimistic to expect ethnic politics to dissipate in Kenya. This requires institutional change as well as a shift in attitude, values and culture like belief in collective prosperity, non-violent settlement of disputes and inter communal trust. For this Kenyan communities and their political leaders still have a great deal to do.