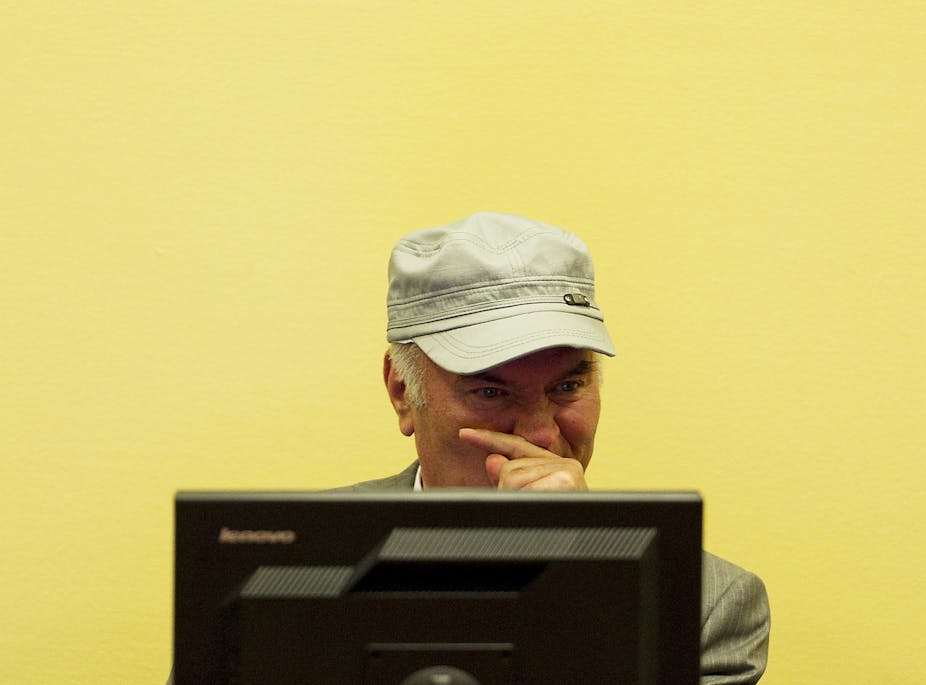

The trial of former Bosnian Serb Army (VRS) Colonel General, Ratko Mladić commenced in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) this past Wednesday.

Mladić’s arrest at his cousin’s farmhouse in Lazarevo in May 2011, made world headlines. Alongside Slobodan Milošević and Radovan Karadžić, he is one of the most high-profile superiors arraigned to appear before the ICTY for atrocities committed in the 1990s Balkans conflict.

Just as soon as the trial started, inadequate disclosure of evidence by the prosecution has resulted in an adjournment three hours into the second day of hearing.

Genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes

It has been almost two decades since the first indictment was issued against Mladic in 1995. The prosecution’s fourth amended indictment was filed in December 2011.

Mladić is alleged to have been part of a joint criminal enterprise, alongside key political figure Karadžić, and other high-ranking civilian and military superiors. Their overriding objective was to “ethnically cleanse” Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats from Bosnian Serb-claimed territories.

In his military roles as Commander of Main Staff, and subsequently Colonel General, Mladić is alleged to have played a pivotal role in the establishment and command of the VRS. It is further alleged that he coordinated and assisted paramilitaries, volunteers and local Serb Forces.

Mladić is charged with two counts of genocide. Genocide requires an intent to destroy, in whole or in part, members of protected groups. In Mladić’s case, the nationality, ethnicity and/or religion of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats constituted the grounds upon which they were targeted for “permanent removal”.

He is also indicted on crimes against humanity - persecutions, extermination, murders, deportation and forcible transfer of civilians.

Mladić was charged with four counts of war crimes: murder, terrorist acts against civilians, unlawful attacks and taking hostages. Artillery, sniper and shelling attacks were part of a systemic attack, and campaign of terror, on civilians in Sarajevo.

Recalcitrant defendants in international criminal trials

On day one, Mladić taunted victims’ families in the tribunal’s public gallery - at one stage, making a cut-throat gesture. Mladić’s inappropriate conduct follows previous outbursts before the tribunal, requests to appear in his military uniform and repeated attempts to subvert the proceedings.

Monash University Law School Associate Professor Gideon Boas, former Senior Legal Officer in the ICTY, highlights some important lessons from the Milošević trial. As Boas notes - Milošević was a truculent defendant, adamant on representing himself in a highly complex, difficult and lengthy case. Milošević’s ill health was exacerbated by the stresses brought on by self-representation. The former head of state died four years into the proceeding and only months out from judgement.

In Mladić’s case, to circumvent his attempts to derail the proceedings - the Trial Chamber has at times appointed a duty defence lawyer to represent him. He has refused to enter pleas to charges he has described as “obscene”, and the Trial Chamber has had to enter not-guilty pleas on his behalf.

Delays caused by non-disclosure of evidence

The ICTY faces difficulties in achieving the right balance between competing fair trial principles, whilst mitigating increasing risks associated with Mladić’s trial. That Mladić is 70 years old, and has suffered three strokes and one heart attack, is no doubt weighing heavily on the minds of all involved.

Trials should not be too long delayed. This fairness principle needs to be balanced against procedural rights afforded to defendants.

It was just prior to the commencement of the trial that ICTY President Theodor Meron refused Mladić’s “unmeritorious” defence motion to disqualify Judge Alphons Orie. On day two, Judge Orie - whom the defence claimed was biased - ordered an adjournment of the trial due to “significant disclosure errors” made by the prosecution.

It is a fundamental tenement of a fair trial, that the case against an accused is disclosed. The ICTY Rules of Procedure and Evidence specifically prescribe that evidence be disclosed by the prosecutor to the accused.

Judge Orie, when apprised of the extent of the prosecution’s non-disclosure, had to adjourn the matter. Otherwise Mladić’s rights to a proper defence would have been jeopardised, and given rise to substantive appeal grounds.

This “clerical error” has further prolonged the trial of a man referred to by his many victims and their families as the “Butcher of Bosnia”.

The further delay to Mladić’s trial is most unfortunate, but, a necessary consequence given the substantive non-disclosure of evidence by the prosecution.

Mladić’s trial is more than likely to exceed three years in duration. The ICTY has difficult challenges to overcome in its management of this proceeding. Whilst time is of the essence, the ultimate objective is a just outcome.

The overarching interests of justice, alongside the fair trial rights of the accused, need to be effectively managed - particularly in a high risk case, and when there is so much is at stake.