Reports of the death of effective antibiotics are no longer greatly exaggerated. The US Centers for Disease Control has reported that a woman in her 70s has died of overwhelming sepsis caused by a bacterium that was resistant to all available antibiotics.

The patient had acquired the infection as a complication of treatment for a fractured hip she received in India two years previously. So-called “pan-resistant” bacteria have been recognised in India and other parts of the developing world for several years and they are now being identified in the US.

Australia is yet to report a pan-resistant germ, but it is only a matter of time. Local bacteria that are resistant to all but a few antibiotics are now common and, although overseas travel is an important risk factor, cases occur in people who have not left the country.

The human race was able to successfully multiply its numbers without the aid of antibiotics up until 1935, the year the first antibiotic was released. So how seriously should we take the sometimes apocalyptic warnings that we are approaching the end of the Antibiotic Age? Unfortunately the answer is - very.

What would happen without antibiotics?

Infection is one of the commonest causes of death following a bone marrow transplant for leukaemia or lymphoma. It is also a serious risk after heart, lung, kidney and liver transplants. Patients undergoing chemotherapy for breast and lung cancer often develop infections when their white cell counts drop.

Many premature babies, whose immune systems are under-developed, contract bacterial infections in the intensive care unit. Even with effective antibiotics, the death rate from infection in each of these settings is high. With pan-resistant bacteria, the death rate will soar.

People who undergo any of the common abdominal surgical procedures (such as an appendectomy, gallbladder removal and bowel resection) will have a much higher chance of developing infections that, since the 1950s, have hardly even been considered. Infections from common elective surgeries, such as hip and knee replacements, will be commonplace. In a post-antibiotic world, the time may come when the risk of infection outweighs the benefit of elective surgery.

The common infection of the leg known as cellulitis occasionally requires high-dose antibiotics in hospital, but most cases are treated in the community. With no antibiotics, cellulitis will return to what it was in the early 20th century – a condition that often required surgical drainage of pus from the deep tissues of the leg and, in the most severe cases, amputation.

Urinary tract infections in women will become more than just a nuisance that can be fixed with a short course of oral antibiotics. Women returning from holidays in South-East Asia have a significant chance of picking up resistant bugs in their gastrointestinal tract that may persist for six months or more. These bacteria can cause cystitis (a bladder infection) that is untreatable with any oral antibiotics.

Men returning from an international trip who undergo prostate cancer screening with a transrectal biopsy can end up with an untreatable bloodstream infection.

Use them and lose them

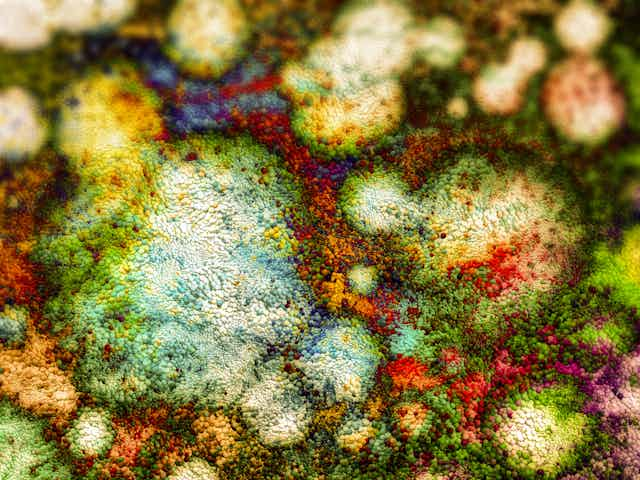

The emergence of resistance to antibiotics is inevitable. When a selection pressure is placed on a bacterium by exposing it to an antibiotic, the “fittest” (resistant) bacteria are not killed and may come to dominate the local population of microorganisms.

Resistance can be slowed by limiting the use of antibiotics to only those who need them, by using antibiotics with the narrowest possible spectrum of activity, and by using the correct dose for the shortest possible time. The widespread use of antibiotics for non life-threatening infections outside of hospital has been one of the main drivers of resistance.

It is not always easy to differentiate between viral and bacterial infections, and doctors are understandably reluctant to miss a bacterial infection. Unfortunately this anxiety leads to millions of unnecessary prescriptions each year. A wrong antibiotic choice in hospitalised patients with life-threatening infections (such as septicaemia and pneumonia) can be a lethal mistake, so initially these people require powerful, broad-spectrum agents.

It isn’t just a problem of medical prescribing. It’s estimated animals receive 80% of the antibiotics used in the US. In animals they are mainly used to boost growth, resulting in resistant bacteria in the human food chain.

Antibiotic resistance is recognised as a global crisis by the World Health Organisation. Its rise can be slowed but not halted. There is an urgent need for new antibiotics, but only one new class of agents has been discovered in the past 30 years.

The development in that same period of the extraordinarily effective antiviral drugs for Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and HIV demonstrate what can be achieved when the mighty resources of the pharmaceutical industry are focused on a problem.

In the meantime, we’ll have to relearn lessons about infection control such as hand hygiene, better hospital cleaning and meticulous attention to sterility when performing invasive procedures that were once second nature to health care workers in the pre-antibiotic age.