The 2014 federal budget implemented a so-called crackdown on what Minister for Social Services Kevin Andrews calls young people who are content to “sit on the couch at home and pick up a welfare cheque”.

The crackdown will change access to income support for people under 30 years of age.

From January 1 2015, all young people seeking Newstart Allowance and Youth Allowance for the first time will be required to “demonstrate appropriate job search and participation in employment services support for six months before receiving payments”.

Upon qualifying, recipients must then spend 25 hours per week in Work for the Dole in order to receive income support for a six-month period. What happens beyond this six months is unclear.

What is clear is that these policy changes, together with the Minister’s accompanying statements, are informed by a deficit view of disadvantaged youth.

It is a view that demonstrates how little politicians know or understand about these young peoples’ past circumstances.

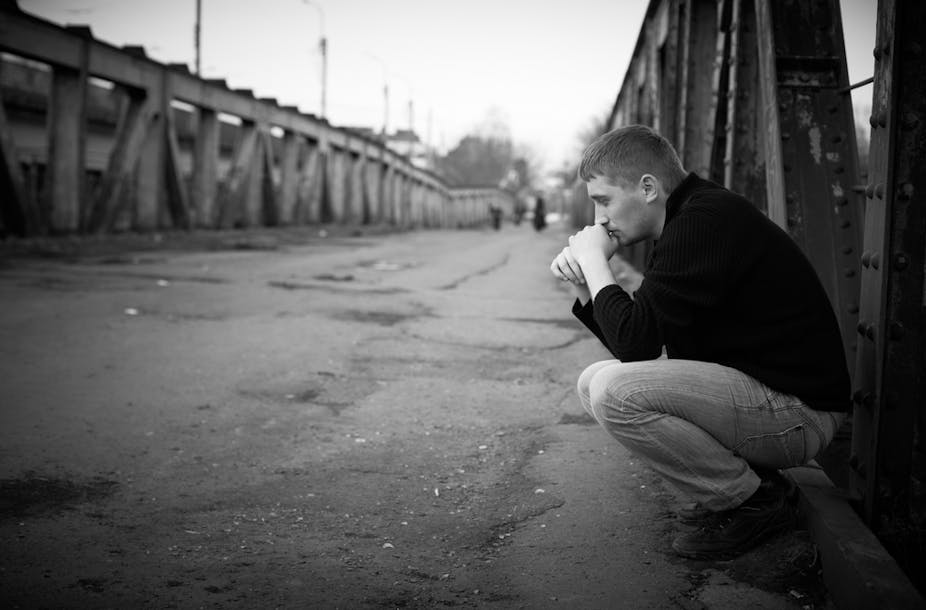

Putting a face on the young people

A recent ARC Discovery project I led investigated the experiences of young people enrolled in special schools for disruptive students in New South Wales.

The kids I have been working with for the last three years have all experienced severe learning difficulties, in addition to receptive and expressive language disorders, as well as family breakdown, child abuse and resulting mental health issues.

The majority report a lack of academic support in the primary years of school, conflict with teachers, and poor peer-relationships. Most are years behind their age peers academically and the vast majority come from severely disadvantaged backgrounds.

By severely disadvantaged, I mean children who have been removed from or surrendered by their parents and children who have moved schools more times than they can count. This was often because their mum could no longer pay the rent on their housing commission home or because she had to flee to a refuge to escape domestic violence.

I also refer to 13-year-olds who speak of “juvie” like it is inevitable, 15-year-olds who cannot read anything more complex than a street sign, an 11-year-old who spent 18 months of primary school travelling in his father’s truck due to rolling school suspensions, and 13-year-olds on medication cocktails that would fell a horse.

I also mean young people who say they want to be builders, carpenters, reptile handlers, lion keepers, paramedics, policemen, lawyers and professional rappers.

However, given the learning gaps and high absenteeism noted by participating school principals, not one of these young people is likely to gain a Year 12 qualification.

Short of a miracle, the majority are destined to join the unemployment line but not one of these young people indicated that this was a life they were planning for themselves.

Help them escape the unemployment line

The special schools know what their students’ futures are likely to be and are working hard to help them into alternative pathways.

The traditional port of call for low attainers and early school leavers has been TAFE, yet TAFE and the role that it can play in the social mobility of disadvantaged young people has not figured in any serious policy considerations since the Dawkins years.

It is as though successive governments have forgotten that 24% of young Australians still do not complete year 12, and that those who do not make it into further education or training are in real danger of joining the long-term unemployment line.

On budget night we heard that the further education sector is to undergo its biggest shake-up since the Dawkins reforms. The demand-driven system is to be extended to include non-university providers offering diplomas, advanced diplomas and associate and bachelor degrees.

Conspicuously absent in the educational measures announced is funding for second-chance education programs and the critical bridging courses that are necessary to support access to further education and training for disadvantaged early school leavers.

These are the young people who are likely to be pushed into the harsh new income support measures introduced on budget night. The result will be to further concentrate financial hardship; an outcome that will not only affect these young people but also their parent/s.

For many of the students I described earlier, home is headed by a single mother who, since the Gillard government’s changes to the single mother’s pension, cannot afford to support them.

Instead of education policy that has been informed by knowledge of where these young people have come from and what is needed to help them achieve their dreams, we get welfare policy that portrays them as lazy couch-potatoes.

The question is why, when a successful outcome for these young people would surely be better in the long run, not only for them, but for the economy too.