Scotland is rarely slow to recognise its literary heroes, from building monuments to Walter Scott to crafting a tourist industry around Robert Burns. However, one major writer remains unclaimed for the canon 130 years after his literary career began.

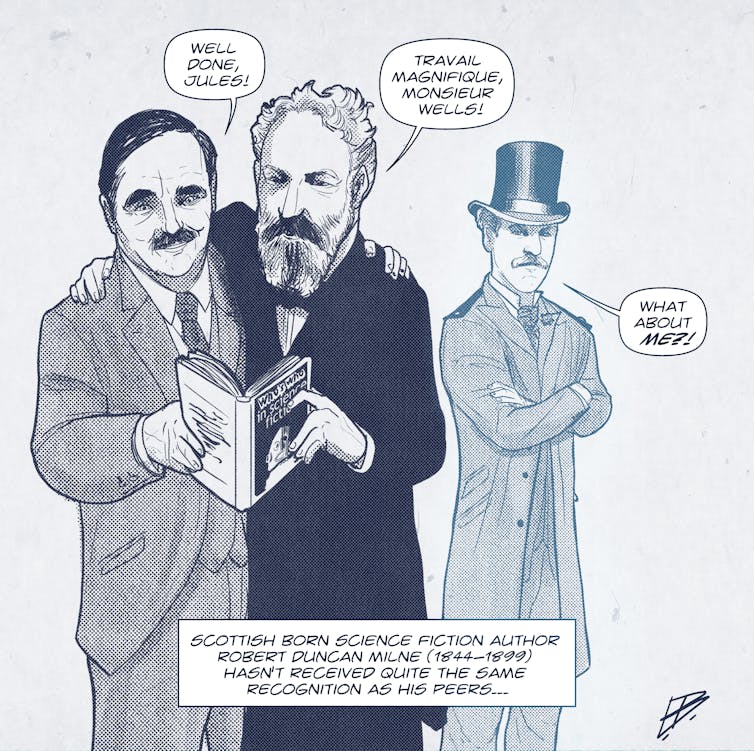

Robert Duncan Milne was an astonishingly prescient pioneer of science fiction who published over 60 stories in the late 19th century. Yet hardly anyone knows his name or how he influenced other leading lights in the early days of the genre.

HG Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) is famously associated with visualising time travel as if watching a series of sped-up moving photographic images, for example, firing the imaginations of the earliest film makers. Yet Milne published a whole string of stories about fantastic technologies for visual time-travelling years earlier.

He also foresaw television, remote surveillance, mobile phones and worldwide satellite communications – not to mention climate change, scientific terrorism and drone warfare, cryogenics and molecular re-engineering of the body.

The American science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz, who published the only posthumous anthology of Milne’s work in 1980, credited him as being, in effect, the first full-time sci-fi writer in America.

Milne reaches America

Milne was born in the small Fife town of Cupar in 1844, the son of a Kirk minister. He was a gifted classics scholar who nevertheless left Oxford without graduating in the 1860s before mysteriously reappearing in California, then the literal Wild West of world-changing new ideas and inventions.

After Jack London-esque stints as an itinerant shepherd, cook and labourer, the aspiring inventor and writer resurfaced at San Francisco’s 1874 Mechanics’ Fair, demonstrating a rotary engine that he had patented. Thenceforth, his scientific articles and fiction appeared regularly in San Francisco’s Argonaut magazine until the 1890s.

The Milne story that presaged HG Wells’ visualisation of time travel is one of his most remarkable, The Palaeoscopic Camera: How Dead Walls Reveal the Scenes and Secrets of the Past (1881). It is a fictional take on one of San Francisco’s most famous citizens, the pioneering photographer Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s animal locomotion studies used the camera as a machine to see movements too fast for the naked eye and reanimated them by projection, inspiring the invention of the cinematograph in 1895 by the Lumières.

Milne seized the idea that photography can reveal things in time and reimagined Muybridge’s process as a fantastic technology that can unearth events from the remote past and replay them as moving images in the present. Thus he anticipated cinema as a medium for visual time travelling years before Wells or the Lumières. As he wrote in the story:

Scene succeeded scene with such exact and wondrous alternation of form and subject that my attention was spell-bound, and I scarcely knew whether I was gazing at reality or not. Color, form, expression of countenance, habitude of dress, demeanor, gesture – all were there, limned to the life.

Milne was read widely in the US and syndicated round the world – though rarely if ever in his native Scotland, alas. His cryogenics story, Ten Thousand Years in Ice, in which a survivor from an ancient advanced civilisation is revived in the present, unintentionally became one of science fiction’s great literary hoaxes. Because of the documentary plausibility which became Milne’s trademark style, readers of a Hungarian newspaper mistook the translation for a factual report.

This anticipated the “realism of the fantastic” associated with The War of the Worlds. The 1938 radio adaptation notoriously panicked listeners in America by transferring such techniques into broadcast media.

Future vision

Though generally enthralled by scientific wonders, Milne’s narrators, like Wells’, are not simply gung-ho optimists about technological progress. They often sound cautionary notes about the double-edged potential of new inventions or processes to disrupt human life or be turned to sinister ends.

In The Eidoloscope, for example, Milne discusses the possibility of being able to replay any action or event from the past on a kind of monitor. It raises concerns about universal surveillance and an end to privacy altogether.

And in A Question of Reciprocity, he proposes being able to steer unmanned aircraft by remote control. He signals how destructive this might be in the wrong hands when a helicopter armed with bombs is used to blackmail the citizens of San Francisco.

Indeed through his writing, Milne created countless imaginary technologies. Some were close to feasibility at the time, but others were way ahead. These ideas, taken on by scientists, engineers and technologists, have fundamentally shaped the networked media-driven world we now live in.

Ironically, scientific modernity cut Milne’s own extraordinary career short. A high-functioning alcoholic, his life was terminated on December 15 1899 when he stumbled in front of one of San Francisco’s new electric street cars. Thereafter his reputation was virtually buried with him. He had never gathered his work together into a published volume in his lifetime and no one thought to do so until Moskowitz decades later.

My colleagues and I at the University of Dundee are now teaching Milne on our MLitt Science Fiction course and developing a major research project about him. This will include a new critical anthology, a graphic novel about his life and career, and a comic book retelling his stories in visual form. We are indebted for Milne’s rediscovery to Barry Sullivan, a postgraduate student.

It is not going too far to say Milne is the missing link between Scotland and the origins of modern science fiction. June 7 was his birthday. I believe the time has come to finally honour this transatlantic science fiction prophet in his homeland.

A plaque in Cupar would be a great start, but more importantly this writer deserves to be much more widely read. Scotland should be looking at ways of giving him the recognition he deserves. Milne should be one of the first dozen or so writers that we think of when we consider Scotland’s literary heritage. Until then, his country is doing itself a great disservice – not to mention the man himself.