I woke up yesterday to a sunny Saturday morning in Melbourne and an SMS message from my eldest son in Glasgow:

I guess you will have heard but there was a major fire at the Glasgow School of Art today. Unfortunately looks like a lot is lost.

This stark message did little to prepare me for the shock of the images from UK news channels.

The Glasgow School of Art building, built between 1897 and 1909, is recognised by architects across the world as one of the major architectural masterpieces of the 20th century. Many architects here in Australia have told me of being overwhelmed by the beauty of the building when visiting Glasgow.

I have special reason to feel enormous pain and loss as I watch this iconic building ripped apart by flames. In 1992, I completed my PhD studies of the building – the PhD that led me into an academic career and ultimately to Australia and my current post.

In the weekend’s news reports, the building is referred to as the work of Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh. While Mackintosh is rightly feted as a great artist, designer and architect, neither he nor the building were so well regarded even in their home city in the mid-1900s. At one point, there was consideration of bulldozing this and other Mackintosh buildings as part of the city’s post-war renewal.

The building was the product of the architectural practice of Honeyman, Keppie and Mackintosh, with the young C.R. Mackintosh the junior partner.

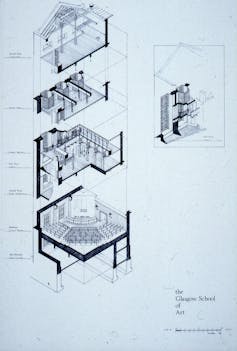

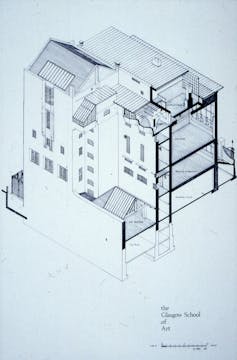

While Mackintosh is frequently referred to as the sole designer of the building, I argued in my PhD thesis – examined by world authority on Mackintosh, Professor Robert Macleod – that while Mackintosh’s hand was clear on the drawings and in the visual aesthetics, the functional planning skill of Honeyman and the technical knowledge of Keppie were evident in the layouts and in the heating systems respectively. Sadly, both these virtues may have contributed to the severity of the fire.

The spatial composition of the School is a work of genius, such that it functioned as a working art school for over a century, with student work appearing to be the root of the fire. I understand that in a survey of the School’s property portfolio at a time when it included several buildings from the latter part of the 20th century, the original building was found to be the only one fit for a practical purpose.

So, it was always occupied by students, using various highly flammable materials, respecting the space but not treating it as the hallowed museum piece that its reputation might imply.

Unfortunately, it is very likely that the old heating system – abandoned in the 1920s – contributed to the speed with which the fire spread from its basement origin to overwhelm the roof space and upper floors.

Built largely of wood, there were many vertical air ducts in the building, running through the full height and no doubt filled with dust, paint particles and other flammable materials. This system was, however, little recognised and until my study an unknown part of the School’s world-class contribution to the history of building.

Contrary to prevailing views that the origins of true air-conditioning – the ability to raise and lower both temperature and humidity independently – lie in the United States in the first decade of the 20th century, these were shown as evident in the Glasgow School of Art.

Keppie had worked with Scottish engineer William Key who, with Robert Tindall, had in 1891 lodged a previously unknown patent that shows the mechanics of true air conditioning. My survey work in the School found traces that clearly showed the integration of Key and Tindall’s air conditioning into the School’s design.

One factor that I unearthed in undertaking my study was that none of the original architects’ drawings showed the building exactly as built. Many details of the design had been subject to fine tuning during construction.

Also, many bits had been modified – with varying degrees of respect for the original – during the life of the building. As such, unless there has been more recent survey work completed, there is likely no record of what exactly existed at the time of this devastating fire.

This brings me to what, for many, may be both a painful and apparently disrespectful conclusion.

The UK chief secretary to the Treasury, Danny Alexander, has already promised central government will give millions of pounds if necessary to restore the world-renowned building.

But I know that to rebuild the Glasgow School of Art to its original design is impossible. Not only are the records likely to be incomplete, but modern reconstruction will require elimination of the fire risks inherent in the wooden construction, open ducts and flowing circulation spaces of the original.

The building as it stood before the fire was, as I stated, not a museum. It was a living space, with plenty of wear and tear, paint spatters everywhere, students’ names carved into bits … a place of ageing graceful beauty that cannot be replaced by some youngster with perfect features. Glasgow has enough modern Mackintosh and Mockintosh.

Today I feel great pain and sadness at this loss – feelings I know I will share with others the world over. But I make a call now for what is left of the Glasgow School of Art to be carefully stabilised and preserved, then for great architects to be invited to design a worthy intervention that will breathe new life into the school.

The memories of the original features that are lost can then be accommodated into a suitable gallery space for reflection on loss, while a new body of students enter a re-born Glasgow School of Art.