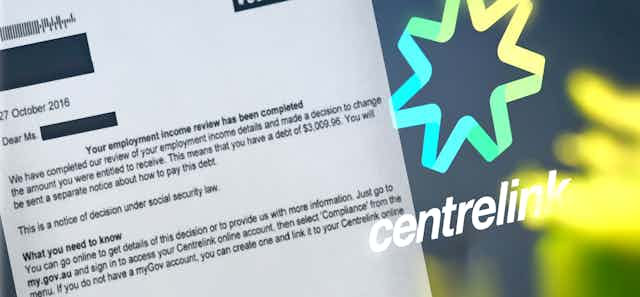

The robo-debt recovery program has been criticised as badly designed and unfair ever since it began in mid-2016.

A year later the Senate Committee on Community Affairs recommended it be put on hold until its design flaws could be addressed, yet there has been a procession of stories since of people having their payments cut off or money demanded because of the application of bad data matching.

The minister for government services has confirmed in parliament that as many as one in five of the debt recovery notices issued might be incorrect, and apologised to a woman who received a debt notice on behalf of her dead son.

How it worked

Robo-debt’s modus operandi was to estimate income that might disqualify someone from receiving benefits using an inaccurate formula, and then to require that person to prove the estimate was wrong.

The class action announced by Labor government services spokesman Bill Shorten and lawyer Peter Gordon on Tuesday, seeks to answer, once and for all, whether those foundations are legally sound.

It will be based on the legal concept of “unjust enrichment”. Unjust enrichment is a common law term that arises when a person has retained something of value to which they are not legally entitled.

Was it “unjust enrichment”?

Access to social security is governed by specific legislation, so an important part of the case will be whether the common law principle of unjust enrichment can be applied to actions that have been taken under that legislation.

In legal terms, if the government passes legislation that allows it to act in a specific way, then that legislation will generally prevail over common law as long as it is not ultra vires (beyond the government’s powers to make) and the people making the relevant decisions have complied with it.

The class action will need to take into account existing appeal mechanisms under the Social Security Act. But those existing mechanisms are often limited to whether the person making the decision has acted in accordance with procedural requirements.

Administrative law is usually limited to procedural fairness rather than fairness of outcomes. For example, when deciding to send a matter to a debt collection service, the question will be whether the criteria were applied and whether they were applied correctly.

It would be an interesting question to apply to an algorithm.

It’s getting more sophisticated…

Despite, or perhaps because of, the problems that emerged with the first iteration of robo-debt, the government has stepped up its reliance on data matching.

Employees may have noticed their payroll data is now sent to the Australian Taxation Office at the time they are paid rather than quarterly or annually as had been the case. There are benefits to this, particularly when you are tracking your superannuation contributions.

And it means the Tax Office data can be matched to Centrelink data in real time rather than estimated later, overcoming one of the major shortcomings of the system, in line with the recommendations of the Senate committee.

…and augmented, with drug tests and welfare cards

Data matching is getting more sophisticated in other ways. Centrelink data is being matched with Medicare data to identify “persons of interest who have a high likelihood of fraudulent behaviour”.

While all Australians want to be sure Centrelink benefits are paid properly, the expansion of data matching has the potential to further victimise social security recipients.

In tandem with proposed drug testing programs and the proposed expansion of the cashless welfare card, there is a creeping stigmatisation of social security recipients.

Read more: Why Centrelink should adopt a light touch when data matching

The safety net that ought to be there to support us when we need it is being unravelled.