Britain was once among the most enthusiastic of slave-trading nations. But just over 200 years ago, the country dramatically changed course and used its naval dominance against the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people, one of the worst historical crimes against humanity.

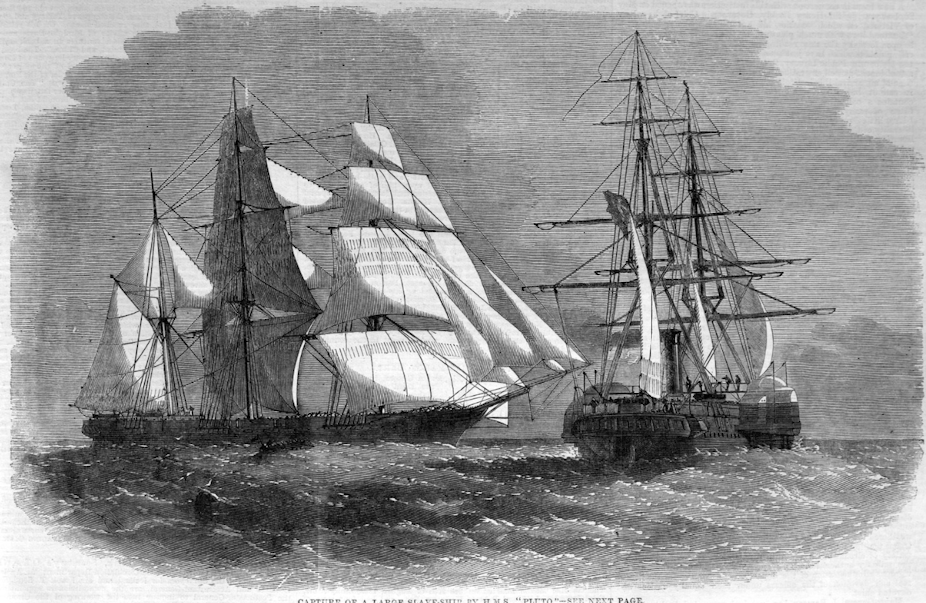

After the Abolition Act of 1807 made British involvement in the transatlantic slave trade illegal, the country switched rapidly to an extensive commitment to enforce its abolition. For the next 60 years, the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron worked to suppress the human traffic between West Africa and the plantations of the Americas, as Britain exerted increasing diplomatic and coercive pressure on nations continuing the slave trade such as Spain, Portugal, France and Brazil.

At its peak in the 1840s and 1850s, British operations off the West African coast involved up to 36 vessels and more than 4,000 men, costing an estimated half of all naval spending – amounting to between 1% and 2% of British government expenditure.

In all, nearly 200,000 African men, women and children were released by the navy. It’s a huge number of people, but represents only a relatively small share of the estimated 3.2 million who were taken from West Africa as slaves between 1808 and 1863. Nevertheless, the work of the West Africa squadron was the first chapter in a long history of British naval campaigns against international slavery, including in the Indian Ocean from the 1860s, and in the Red Sea and Persian Gulf in the 1920s and 1930s.

Witnessing slavery first hand

My new book Envoys of Abolition looks at the personal experiences of British sailors serving in West Africa, including their relationships with the African people they met while intercepting and detaining slave vessels at sea, and while spreading the British anti-slavery message on shore. Alongside their official duties of law enforcement, chase and capture, sailors’ experiences of anti-slave trade service included their roles as negotiators, guardians, humanitarians and “liberators”.

Conditions of this service were extraordinary, and the naval personnel involved need to be recognised as more than just sailors performing a job. Their stories uncover notions of duty and a sense of moral and religious imperative to end the slave trade, but also raise questions of racial identity and the meaning of freedom.

A snapshot of the human interactions at the heart of slave trade suppression is the “prize voyage”, where intercepted slave vessels were transported to Admiralty Courts, usually in the British colony of Sierra Leone. The terrible conditions for those captive aboard slave vessels on the infamous Middle Passage across the Atlantic meant dysentery, fever, small-pox and eye diseases were common, compounded by over-crowding and poor ventilation below deck. These conditions were not easily alleviated if the ships were taken under the control of the Royal Navy.

In a letter written home from Sierra Leone in 1863, naval officer James Bowly described how on one captured vessel only around 200 of the 540 original captives survived the passage to Sierra Leone:

They were in the most dreadful condition that human beings could be in … I should never have believed that anything could have been so horrible … some of them mere walking skeletons.

Diseases were easily transmitted to sailors, and the squadron suffered significantly higher mortality rates than other naval stations in this period. As one officer noted: “I dread sending away an officer and men in such a floating pest house!”

Witnessing the distressing realities of the slave trade was for many a transformative experience. Commodore John Hayes, a hugely experienced officer, witnessed cases “too horrible & disgusting to be described”. His compassion for the enslaved led him to plead, in his correspondence with his seniors: “Gracious God! Is this unparalleled cruelty to last for ever?”

Sir George Collier, appointed as the first leader of the squadron in 1818, believed the dreadful realities of transatlantic slavery roused “active benevolence” and “philanthropic feelings” in his fellow crewmembers. However, the conditions of the prize voyage could also contribute to tensions between sailors and recaptured Africans.

‘In the hands of new conquerors’

Regrettably, few African testimonies survive, although it’s possible to create an idea of the conditions of captivity that led former slave Mahommah G. Baquaqua to declare: “my wretchedness I cannot describe.”

Were recaptured Africans even aware of a favourable change in their circumstances? Born in present-day Nigeria, Samuel Ajayi Crowther was released from a Portuguese slave vessel in 1822 and went on to have a remarkable career as a respected missionary and, later, the first African Anglican bishop. Crowther’s first-hand account reveals the distrust inherent in these initial encounters with the Royal Navy. “We found ourselves in the hands of new conquerors”, he wrote, “whom we at first very much dreaded.”

Naval officers were tasked with maintaining order and discipline on prize vessels as on any other ship. Tensions were exacerbated by language barriers, as Africans enslaved from diverse communities invariably spoke different languages. Racial prejudices of the time also played a part.

Some naval men were prepared to assert control in ways reminiscent of those used by the trade they were attempting to suppress. When an African man on his prize vessel was accused of stealing a 4lb piece of beef, Lieutenant Philip de Sausmarez tied the man in the rigging with the piece of beef suspended above him, and made the slaves process around him as an example.

While Britain’s abolitionist campaign was presented to the rest of the world as a shining example of the country’s benevolence, the reality revealed in the accounts from the front line is more nuanced. The granting of liberty (or more accurately, British perceptions of liberty) to captive Africans was riddled with ambiguities.

This continued after recaptured Africans were resettled in British territories, where, rather than being repatriated, they became part of the wider British anti-slavery campaign to end slave trading within Africa by “civilising” the continent via Christian education and European commerce. We should also remember that until the Emancipation Act of 1833, many Britons still owned slaves in the Caribbean.

The British commitment to anti-slavery operations in this period is rightfully commended. The insight offered by the personal experiences of British sailors from the West African coast, however, serves to remind us of the complexities of British abolitionism in this period.

Envoys of abolition: British Naval Officers and the Campaign Against the Slave Trade in West Africa.