Jobs growth is a centrepiece political promise for both political parties but nothing has been said on what type of jobs these will be. At least President Obama told Americans in his 2013 State of the Union address that he wanted growth of “middle class” jobs implying stability, good pay, and decent conditions.

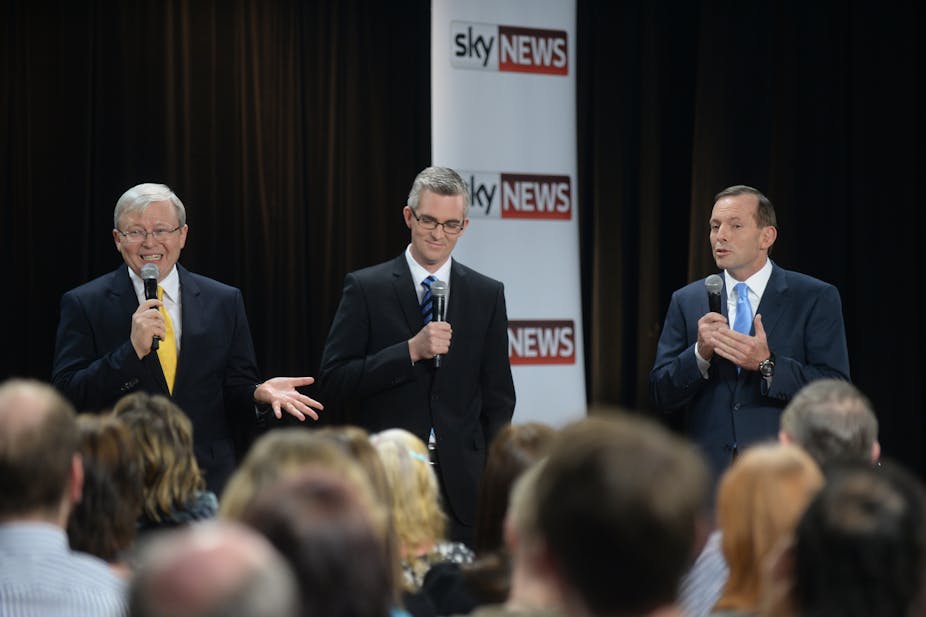

But Australians have only been given a generic “more jobs” promise from our leadership contenders as we saw in the last People’s Forum. One pointed question was asked about what the parties propose to help underemployed and casualised workers, and neither prime minister Kevin Rudd nor opposition leader Tony Abbott offered any more than bland generalities.

Abbott talked about how a stronger economy will be the best medicine and that his priority is getting the unemployed into jobs. Rudd also went down the strong economy track but mentioned Government programs to assist young people with trades training and a $1000 incentive payment for 2500 businesses each year to take on workers aged 55+. More details on assistance for the unemployed were revealed in the ALP election campaign launch. But none of the existing programs or new announcements by either parties are greatly relevant in relation to underemployment and casualisation.

Despite the lack of traction on the issues in this election campaign, the nature of future jobs growth is an outstanding question for whoever takes office on 7 September. Underemployment and casualisation as significant features of the Australian labour market over the last 20 years have seriously eroded opportunity and living standards for many. New findings from Australia’s large longitudinal surveys tell us why.

Why underemployment matters

Current ABS data shows that involuntary underemployment stands at 7.3%. Combined with unemployment, that means around 1.6 million people, or around 13% of the workforce, have no work or not enough work. In the first half of 2013 9.5% of the female workforce, compared to 5.4% of the male workforce, had insufficient hours of work.

From July 2014, the ABS is planning to publish underemployment statistics as part of the monthly labour force survey, as opposed to the present rate of every three months. This will help to keep the issue on the public agenda. As unemployment rises next year to 6.25%, it will be especially important to monitor trends in underemployment.

The effects of unemployment/joblessness and underemployment (short part-time hours) are explored in a newly published paper by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. The research, based on the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, shows that that the most disadvantaged families are indeed those where parents are not in paid employment. However, families dependent on jobs with short part-time hours are also significantly disadvantaged.

An important finding of the research is that the benefits of paid employment are more effectively achieved when parents move from jobs with short part-time hours to jobs with full-time or long part-time hours. There are some benefits gained from moving from joblessness to short hours part-time jobs, but these are limited. We know from ABS data that many people in short hours jobs - those involuntarily underemployed - want more hours of work.

This means we need full time jobs growth and a pool of long part-time hours permanent jobs (of around 25-30 hours per week) for those who want them – especially needed for women trying to balance work and family. Can someone please ask Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott about their plans to grow these jobs?

Transitioning from casual to permanent jobs

Of course, politicians trot out the old adage that it is always better to be in any job than out of a job. Then the logic goes, it is easier to move from a casual, short part-time hours job to a permanent full-time or long part-time hours job. This is a central pillar of Australian welfare-to-work policy and a view adhered to by many community leaders.

Generalised promises of jobs growth fit with such airy assumptions because they don’t require attention to the quality of jobs that are created. There is of course an element of truth in it but new evidence derived from the Melbourne Institute’s HILDA survey makes it a contestable proposition.

In a recent article, labour market researcher Dr Ian Watson interrogates HILDA data on whether casual (mostly part-time) jobs are indeed a bridge to better employment or whether they are a trap with little opportunity for advancement.

Dr Watson finds that there is a significant entrapment effect within casual employment, especially for women and for workers over 45. He also finds a geographical dimension to the entrapment effect in areas of socio-economic disadvantage. While casual jobs can lead to permanent jobs, depending on various factors, there is also a high rate of transition to joblessness and a high rate of long term continuity in the casual job. This carries with it all of the disadvantages I pointed out in an article on workforce casualisation last year.

The dynamics behind the entrapment effect are complex but two factors stand out from the HILDA research. The first is that, because of its nature, casual employment serves to undermine labour force attachment, which is the single most important predictor of good future labour market outcomes. Casual jobs mean workers are more likely to be in and out of different jobs, as well as cycling in and out of unemployment. Such fragmented workforce attachment undermines the chances of finding secure, permanent employment.

The second factor is that much casual employment is specifically designed to be a ‘dead-end’ within many firms. These jobs are part of ongoing workforce arrangements in many industries as noted in my workforce casualisation article. They are not ‘probationary’ jobs and they are not designed to offer pathways to permanency.

This latest analysis of HILDA data points to some very uncomfortable issues about the nature of jobs growth. If we are to seriously address issues of women’s labour force participation as so passionately argued in relation to the Coalition’s Paid Parental Leave Scheme, and organisations such as the Grattan Institute, then more ‘good’ jobs to facilitate the transition out of casual, part-time work are necessary.

Equally, the entrapment of older workers in casual jobs is very challenging, as policy demands continuing labour force attachment until the pension eligibility age of 67. Older workers will need decent jobs to successfully achieve this policy goal without creating significant pools of economically disadvantaged people in their pre-retirement years.

The labour force participation of women and mature age people are vital for productivity growth according to the same Grattan Institute report.

New jobs post resources boom

As unemployment trends upward and the economy undergoes its post-mining-boom “transition”, Australians deserve better answers on the nature of future jobs growth than the ones offered in this election campaign.

Job security is a basic building block for stable family and community life, and arguably for economic development itself. For political parties to leave it out of their policy reforms is, simply, negligent. In addition to the economic and industry policies for a strong diversified economy generating “good” jobs, it is crucial to establish labour market and social policies to break the cycle of entrapment in casual, low end jobs

Bring on some plans for more “middle class” jobs.