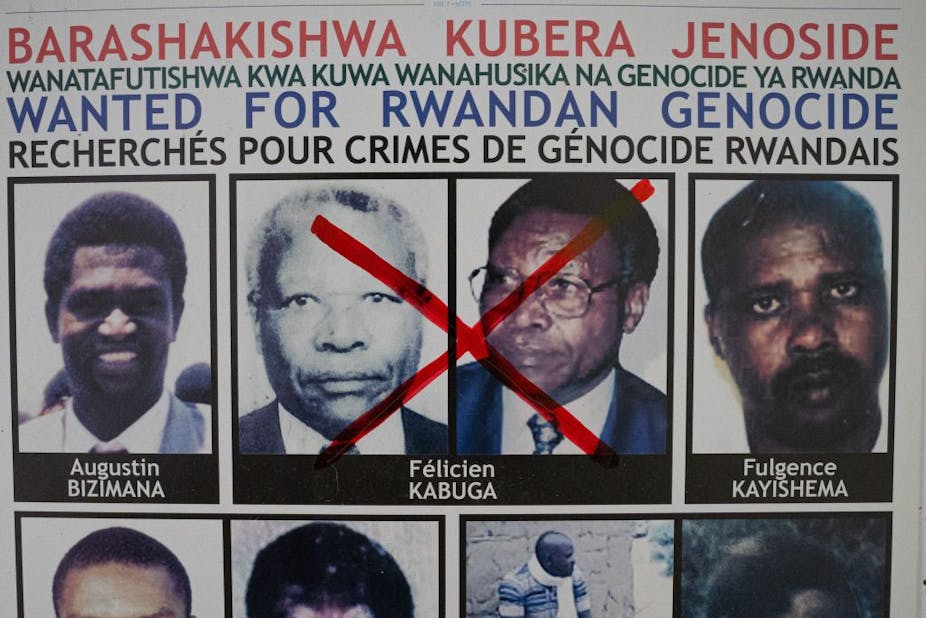

The man accused of supplying the funds to import the primary tools of the genocide – machetes – ahead of Rwanda’s 1994 genocide has been captured in France. Félicien Kabuga is alleged to have been the main financier of Hutu extremists in the 1994 mass killings against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

An estimated one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed within a 100 day period.

Prior to the genocide, Kabuga was a well-known successful businessman within Rwanda. Under the regime of President Juvénal Habyarimana, which ran from 1973 to 1994, he held significant political power.

When the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), backed by Uganda’s army, advanced to take control of the country, Kabuga fled. As did other members of the genocide government.

In 1997, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda – an international court established by the UN in 1994 to judge people responsible for the genocide – indicted Kabuga for his role.

The tribunal, which was located in Arusha, Tanzania, was dissolved in 2015. Its work was taken over by the United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. It was set up to perform the remaining functions of both the Rwanda tribunal and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Kabuga, who is 84, appeared before a French court this week. It will make the decision on whether to hand him over to the tribunal, which is based in The Hague, Netherlands and Arusha. Kabuga has asked to be tried in a French court.

The International Criminal Court was set up to hear cases of crimes against humanity, genocide, and aggression crimes. The exceptions are cases related to Rwanda and Yugoslavia, which go to the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. It is the primary judicial agency responsible for cases against former genocide perpetrators in both countries.

The job of both the International Criminal Court and the criminal tribunal is to promote international justice. This means cases are decided and orchestrated by international judges, lawyers and institutions. The courts also enforce decisions. The rationale is that they promote universal concepts of justice over local justice.

But Rwandans are sceptical of the tribunal, just as they were of its predecessor. Through my work in Rwanda I found that many Rwandans don’t trust the international community’s intentions for justice. This has been fuelled by the ineffectiveness of delivering justice and reconciliation for those affected by the genocide.

Genocide survivors would, therefore, ideally want Kabuga to be prosecuted in Rwanda. But this won’t be possible – for legal and for political reasons. On the legal front, Rwanda’s National Public Prosecution Authority has already publicly stated its commitment to helping the tribunal.

On the political front, the Rwandan government needs to balance domestic apprehension with diplomatic relations. Turning its back on the tribunal could stir up a hornet’s nest and hurt fragile relationships with countries, like France.

Scepticism

From my experience working in Rwanda, Rwandans perceive international-based justice as aiding the conscience of the international community, which failed to intervene before or during the genocide. Many Rwandans believe they’re trying to remove this guilt by promoting justice for international audiences rather than for victims.

This is bolstered by the fact that during the 20-year existence of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, it prosecuted 93 people and convicted only 61. By comparison Rwanda’s local gacaca courts, which operated between 2001 and 2012 and processed crimes committed during the genocide, would give the accused a chance to confess and try to reconcile with those they affected or defend their innocence. Those who admitted their crimes often received fines and community service while those who pleaded innocence were found guilty were given jail sentences. An estimated two million cases were tried. Around 1.6 million were found guilty or confessed to their crimes. Rwandans hail the success of the courts as they fostered reconciliation and justice for Rwandan society.

In addition to this, the multiple early releases of criminals convicted by the UN tribunals introduces even greater scepticism.

During my research, Rwandans often wanted to be able to see and confront those who had either killed family members or raped them.

They argued that having these individuals face justice in another country hindered justice. They felt the accused didn’t truly pay for their crime, whether through prison sentences, retribution or reconciliation. And those convicted in the international system received prison sentences that were often more comfortable in terms of access to resources than they would have been in Rwanda.

Complications

Kabuga’s case is complicated. The original warrant for his arrest was issued by the now-dissolved International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Logic would suggest that this should now simply fall under the jurisdiction of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals.

As a result, Rwanda is not in a position simply to request Kabuga’s extradition.

There are other considerations against his extradition, even if it was possible.

First, there are question marks over whether Rwanda’s judicial system could give Kabuga a fair trial. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have accused Rwanda’s judicial system of unfair practices and heavy political interference.

Second, France might not want to extradite him given old alliances between the French government and the old Habyarimana regime. Researcher Andrew Wallis shows how this relationship helped to facilitate the training of the genocide killing squads, the interahamwe. It also facilitated the escape of genocidal leaders into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and France.

Another consideration is that there are still Rwandans who are alleged to have been involved in the genocide who have never been brought to book and who reportedly continue to reside in France. Kabuga might be the most infamous European resident, but he’s not alone. One example is Agathe Habyarimana, the former wife of the Rwandan President and a primary actor during the genocide’s planning, who lives in France.

The unfolding of what happens next, however, rests with the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals.